See the Water Resources chapter for an introduction to farming in semi-arid regions.

- Zai Holes Harness Termites to Increase Crop Yields

- Grass Mulch: An Innovative Way of Gardening in the Dry Tropics

- Colored Plastic Mulches

- Thick Mulch for No-Till Gardens

- Rice Hull Mulch

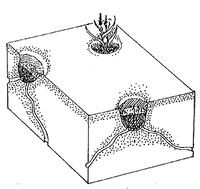

ZAI HOLES HARNESS TERMITES TO INCREASE CROP YIELDS. Tony Rinaudo in Niger wrote of his experience using zai holes [see picture]. "Oxfam, working in Burkina Faso, promotes this method of tillage. This is a traditional practice of digging a 20x20 cm hole 10 cm deep during the dry season and filling it with mulch such as crop residue or manures. This  leads to increased termite activity [note termite tunnels] which, in turn, increases the rate of water infiltration when the rains come [see dotted areas on the diagram]. Millet is planted in the individual holes, which also help protect the seedlings from wind damage (100 km/hr winds at planting time are not uncommon).

leads to increased termite activity [note termite tunnels] which, in turn, increases the rate of water infiltration when the rains come [see dotted areas on the diagram]. Millet is planted in the individual holes, which also help protect the seedlings from wind damage (100 km/hr winds at planting time are not uncommon).

"Where farmers are using it, it is making a big impact on crop yields. Soils here are infertile and if farmers have manure at all they just broadcast it on top of their fields. Much of this is baked, blown and washed away. If the manure and organic matter are placed in a zai hole, losses are minimized and nutrients are concentrated where the plant can use them. Crop plants have a competitive advantage over weeds that are not in the zai hole.

"Zai holes also allow greater water infiltration. The technique was originally used for hard pan soils which are uncultivatable using traditional farming methods. We convinced one farmer to try zais on a small plot of barren land. He did and harvested 100 kgs of corn and 15 kgs of sorghum. The next year farmers in 20 villages dug over 50,000 zai holes! We urged farmers to also try zai holes in their sandy soils. The results were so convincing that many are now digging holes on their own initiative." Tony also wrote of one area in which millet yields were often less than 350 kg/hectare; with zai holes, the yields reached 1000-2000 kg/ha. Farmers in 87 villages dug almost two million zai holes for their millet.

"For some time we have been trying to re-establish cassava as a major crop in the district. There have been more failures than successes because of the harsh climate and poor soils. ...In 1993 we only received 1/3-1/4 of the average rainfall (130-240 mm). In spite of this, because we insisted that farmers dig zai holes, 80% of the 44 ha planted survived. Even in good years we have never had such a high success rate using other planting practices."

Tony also added, "Keep an eye on developments in the food use of Australian acacias. I believe these trees will be very important in semi-arid to arid subsistence agriculture in the future. Last year farmers here planted over4,000 trees with a view to food production. They did this with no promise of food or money payments from us."

Chris Reij of the Free University of Amsterdam presented to the Club du Sahel some of his findings on zai holes in Burkina Faso, where they are an adaptation of a traditional planting method. The following is a summary taken from an article sent to ECHO. The zai or planting pockets are generally 25-30 cm across and 15-20 cm deep, spaced 80 cm or so apart. They are often dug on land so badly degraded that water cannot infiltrate, so the holes collect and concentrate runoff. Organic matter added in the hole provides nutrients for the plants and stimulates termite activity, which can improve the hole. In one area, farmers with zai holes harvested 960 kg/ha of sorghum, while others harvested 610 kg/ha. Tree seeds have also been successfully established in zai holes. A major advantage of these planting pockets is their ability to efficiently harvest rainfall and reduce runoff, thus improving overall soil moisture and fertility. Farmers in Burkina Faso also spread straw on their fields to achieve the same benefits.

Note that different species of termites behave differently, so a technique you read about in EDN may not work where you live. Victor Sanders showed me termite nests high up in trees in Haiti. He tried painting the trunk with neem leaf tea, which was reported to stop termite damage in Mali. It had no effect in keeping this kind of termite from nesting in the tree. The zai hole technology described above is used where the "composting" species of termites is present, able to convert and enrich organic matter into good soil for the seedlings. However, the water harvesting and other benefits of this idea could be helpful even where there are no such termites.

GRASS MULCH: AN INNOVATIVE WAY OF GARDENING IN THE DRY TROPICS (by Scott Sherman). When I visited Jamaica, I learned that farmers in south St. Elizabeth Parish were growing a good crop of scallions. What was unique is that they relied on rainfall in an area that is normally too dry for intensive vegetable production without irrigation. In fact, they were growing tomatoes, cucumbers, carrots, green beans etc. where traditionally yam, cassava, tree crops and a few drought tolerant legumes predominated. Working with the Jamaica Agricultural Foundation and the University of Florida, Mac and Pat Davis set out to study this indigenous system of growing vegetables in a guinea grass mulch. The following is based on their two-part study of scallion production.

Rainfall averages 125 cm (50 inches) annually during two brief periods in the spring and fall. In addition warm temperatures and high winds combine to rapidly dry the soil after the rains. Farmers have found that mulching with guinea grass (Panicum maximum) not only conserves moisture, but offers other benefits as well.

Rainfall averages 125 cm (50 inches) annually during two brief periods in the spring and fall. In addition warm temperatures and high winds combine to rapidly dry the soil after the rains. Farmers have found that mulching with guinea grass (Panicum maximum) not only conserves moisture, but offers other benefits as well.

In the study, all critical steps (i.e. mulching, planting, cultivation, and harvest) were carried out by local farmers in accordance with local practices. Replicated plots were all treated identically (weeded, mulched with a layer of guinea grass and planted) except that after planting the mulch cover was removed from half the plots. Undisturbed fallow plots were left adjacent to each replication for comparison purposes.

Plots mulched with Guinea grass were found to have significantly lower soil temperatures than the unmulched plots. [Ed: Based on a graph in the article, afternoon soil temperatures appear to have averaged about 4øC less with mulch.]

Mulched plots maintained a significantly higher soil moisture content than unmulched or fallow plots. As the dry season progressed and moisture became limiting, growth rates in the mulched plots were superior to those of the unmulched plots (leaf counts were 40% higher at first harvest).

Guinea grass mulch also greatly reduced the amount of weeds (weed counts being up to five times as great in the unmulched plots). Plots were harvested five times. Total yields, marketable yields, and mean bulb diameters were all greater in the mulched plots than the unmulched. Over the course of the experiment, mulched plots produced 75% more bulbs than unmulched plots.

According to Mac, the mulch system is used by all the farmers in the area and no vegetable production is attempted without it. In addition to providing mulch for the principle crops, the grass is also an important part of the crop rotation, serving as a cover crop and sometimes as food for animals. While most farmers keep part of their land in grass and part in vegetable production, farmers with very small farms purchase the grass needed for mulch while those with larger farms grow extra for sale.

The second study focused more on soils, which in the area are well-structured, red or brown bauxitic loams with high aluminum content and near neutral pH. In addition to the benefits mentioned above, this study showed a strong correlation between mulching practices and extractable soil phosphorus.

This finely tuned system appears to be well adapted to growing scallions and other vegetables in that climate. The Davises believe that similar grass-mulch systems could be adapted to other dry areas. Guinea grass seems to be a particularly good mulch because it easily reseeds itself, produces a lot of biomass, dries down quickly and decomposes slowly. While preparing mulch requires extra labor, less time is spent in weeding, watering, etc.

Might such a system allow farmers in other dry areas to intensively produce certain vegetables where they may not otherwise be grown? The author believes so. Such a system would not only increase the farmers' profit potential over traditional crops in a region, but also provide a means for improving the nutritional status of a community. Mac suggests "the best approach would be to begin on a small scale with subsistence garden plots until farmers become familiar with the technique and some marketing infrastructure can be developed." We would be interested to hear if any of our readers have run across similar systems. Gene Purvis, now working in Costa Rica, says that he used a grass mulch system in Panama. Normally his garden took daily watering. He reduced the time of each watering AND reduced the frequency to two times a week by running poly pipe with small holes drilled in it under a cover of chopped paragua grass. He said that any tough, slow decomposing grass, when cut dry, would work well. Rice hulls worked well. Chopping the grass had several advantages.

Martin Gingerich in Haiti learned about a traditional system using Guinea grass in Haiti. This is in an area near La Valee Jacmel at about 800-1000 meters and 2,000 mm (80 inches) of rainfall. He wrote, "Just like the example from Jamaica, the system is used by all farmers in the area and no planting is attempted without it. We couldn't find anyone who remembers when people started using the system. It is older than those using it today."

"Farmers grow mostly corn, beans and some cabbage. There are plots that have only Guinea grass, often owned by larger landholders. Once a year the grass is harvested. A farmer wanting to plant a grain crop in the coming months will purchase and harvest a plot of Guinea grass, which he spreads over the entire field that he intends to plant. These are not large fields. The next step is to tie an animal in the plot to eat and trample the grass. They use horses, burros, mules, cattle and goats. Pigs are tied near the house and their refuse is carried to the field. After the farmer removes the animal from the field he lets it set 2-3 weeks. He then deeply tills the field with a pickaxe, incorporating some of the Guinea grass and leaving some on the surface. Planting is soon after tillage."

COLORED PLASTIC MULCHES have been found to improve yields and fruit quality in some vegetable crops, according to studies around the US. Black plastic mulches reduce weeds, conserve soil moisture, and warm the soil in cold climates. Colored mulches provide these benefits while also reflecting light up to the plants, giving yield benefits such as larger fruit or earlier maturity. Crops seem to have "preferred colors"; one review (in AVG 2/95) cited yield increases of 14-22% over black mulch in cucumber (with red mulch), peppers (yellow, silver), squash (blue, red), and tomato (red, brown).

We called USDA researcher Dr. Michael Kasperbauer, who studies plant response to the light spectrum. He explained that not all shades of color have the same effect on yields. The key factors are the amount of reflected far-red and the ratio of far-red  to red light, which can only be measured with a spectroradiometer. A high FR:R ratio of the reflected light stimulates above-ground growth, so many fruit crops respond favorably on certain red mulches. Tomatoes on red mulch yield 15-20% more fruit during the first two weeks of harvest than plants on black mulch. Cotton plants produce more bolls with longer fibers. Pigments which reflect a low FR:R ratio, in contrast, stimulate root growth.

to red light, which can only be measured with a spectroradiometer. A high FR:R ratio of the reflected light stimulates above-ground growth, so many fruit crops respond favorably on certain red mulches. Tomatoes on red mulch yield 15-20% more fruit during the first two weeks of harvest than plants on black mulch. Cotton plants produce more bolls with longer fibers. Pigments which reflect a low FR:R ratio, in contrast, stimulate root growth.

Some colors (such as yellow) attract insects, and growers can use this factor in pest management. In one trial, cucumber beetles infested yellow-mulched rows first; it may be possible to attract pests to one area of a field for spot treatment. Colored mulches tend to cost more than black plastic, and manufacturers have yet to standardize the color intensity in the mulches for best production. This idea may be worth some experimentation in your fields. Research in this area began by painting black plastic with different colors. Let us know your results.

THICK MULCH FOR NO-TILL GARDENS. I (MLP) first read of this method of gardening in Organic Gardening where it was referred to as permanent mulch gardening. My reaction was that there must be something wrong with anything so easy or everyone would be using it. But our garden has performed so exceptionally well with so little work using this method that we have now converted all of our growing beds to this system.

Ruth Stout first popularized this method in her book No-Work Gardening (Rodale Press). She noticed that under a small stack of hay that she removed in the early spring, there was no need to till the ground. From that time on, her garden had at least a 6-inch (15 cm) layer of mulch 12 months of the year. At the appropriate seasons she simply removed mulch from a row or spot for a transplant, and planted.

The first season. We began our no-till garden in an area of well-grassed lawn. In several years of continuous production, it was never plowed, cultivated, spaded or hoed. The first season it is necessary to do some extra steps if you start with an uncultivated area as we did. It is described in the March 1981 issue of Organic Gardening in an article by Jamie Jobb called "Tossing an Instant Garden." (ECHO will send a copy of this article to overseas development workers who request it.) A layer of newspapers is spread over the area. They should be no less than 3 sheets thick and well overlapped at the edges. Then organic materials of any kind are placed on top. We use either chipped wood that is given to us by the power company when they trim along the power lines, or grass clippings. You could experiment with other materials that may be available to you such as rice hulls, sugar cane bagasse, tall cut grass, leaves, coffee pulp, etc. The method works because weeds are not able to push their way up through newspapers and a layer of mulch, but roots can go down through wet newspaper. Wherever a seed is to be planted a small mound of earth is placed on top of the newspaper (or a narrow row of soil about one inch thick is used if seeds are small and to be planted closely together). The mulch is then pulled back against the earth and a thin layer  put on top of it to prevent drying of the soil. The seeds must be watered more frequently than when planted in tilled soil because the thin layer of soil can dry out quickly. When we pulled mature plants at the end of the first season we found that some roots had gone through the paper and others had grown along the top of the paper to the first edge, then underneath for normal growth. Transplants do surprisingly well when simply planted into the sod through a hole cut in the paper.

put on top of it to prevent drying of the soil. The seeds must be watered more frequently than when planted in tilled soil because the thin layer of soil can dry out quickly. When we pulled mature plants at the end of the first season we found that some roots had gone through the paper and others had grown along the top of the paper to the first edge, then underneath for normal growth. Transplants do surprisingly well when simply planted into the sod through a hole cut in the paper.

Subsequent seasons. The procedure with newspapers is for the first season only. Before the season is over you will find that the newspaper and the sod have decayed and turned to compost. From then on if you keep a layer of mulch about 6 inches thick over the area, the soil beneath will be ready to plant whenever you wish. Our garden has been in continuous use since the day it was first planted. We use the word "no-till" because it is analogous to the system of farming by the same name in which herbicides are used just before planting, then seeds are planted directly into unplowed sod. However, this method uses no herbicides.

What are the advantages? (1) Gardens can be started in any area without the need to plough or spade. You can plant in areas that would be difficult to plough, such as around dead trees or in rocky soil. Grasses and other weeds are better controlled than if the ground had been cultivated. (2) There is much, much less work involved in controlling weeds. But it is a no-till, not a no-work, garden! It can take a lot of time gathering and placing the mulch periodically around the plants. And some weeds will come up that must be removed. (3) Less water is needed for irrigation. (4) The soil is kept cooler. This can be a disadvantage, however, for colder areas. If soil temperatures are too low, the mulch can be raked back in areas to be planted a few days before planting, so that the sun can strike the soil directly. The soil will be dark after a few months of no-till gardening and should warm up quickly. (5) Soil moisture and temperature are more uniform, an advantage for most plants. (6) Nematodes will likely be kept under control. The soil environment is much less suited to nematode growth than, for example, the hot dry sand found in our area. Furthermore, some fungi found in the decaying organic matter will kill nematodes. We have had some signs of root-knot nematodes in the no-till garden, but they have not been a problem after the first few months of operation. It is almost impossible to garden in the same plot for more than one season here without the heavy use of nematicides with normal gardening techniques. We have not yet had to use any nematicide. (7) The only need for a compost pile is for a small one to put large or diseased plants or weeds. When the mulch decays, it is automatically compost and is already in place! Earthworms will soon help carry organic matter down into the soil. (8) Soil erosion from sloping land should be less of a problem.

We periodically add a fertilizer with complete micronutrients. This is necessary in our sandy soil and high rainfall. If you wish to use completely organic methods, remember that you have a mulched garden but not a composted one until at least one season has passed and the mulch has had time to decay. We have not had problems with acidity in spite of all the wood chips that we use. If this becomes a problem you would need to use lime.

At first thought you might think that we would run into a nitrogen deficiency by adding so much undecomposed organic matter. As you probably know, adding a lot of fresh organic matter with a lot of carbon and little nitrogen can actually harm plant growth the first season. The reason is that the micro-organisms use up all available nitrogen in the process of decaying the rest of the material. This nitrogen will become available later when the microorganisms die, but it presents a short term problem. The no-till garden does not have this problem because the mulch is not incorporated into the soil. All of the decay is taking place above-ground. So there is no way for microorganisms growing in the mulch to remove nitrogen from the soil. Once the mulch is decomposed it is incorporated slowly into the soil by leaching, mechanical mixing during the planting process and by earthworms.

We have had no unusual problems with insects or other pests. There is always the possibility that in your area there will be some pest that will find the mulch to be an ideal home and may give you problems. People often ask if inks on the newspaper will add toxic heavy metals. Such metals are only found in colored print. Anyhow, such a small amount of newspaper is used, and only once, that we consider it perfectly harmless.

I believe that the no-till gardening method may give you far better gardens with much less work. Some ECHO visitors who could no longer garden for health reasons are gardening with the no-till method! But as with nearly everything that we  suggest, it is presented as an idea with which you can experiment under your conditions. Only you can evaluate its potential for your area. It should certainly be thoroughly tried before introducing it into the community. We will be very interested to learn of your success or problems with it. Please let us hear from you if you try it.

suggest, it is presented as an idea with which you can experiment under your conditions. Only you can evaluate its potential for your area. It should certainly be thoroughly tried before introducing it into the community. We will be very interested to learn of your success or problems with it. Please let us hear from you if you try it.

There is only one disadvantage that we have found to this heavy use of mulch. It tends to frost on top of mulch at a few degrees higher temperature than elsewhere. Possible problems we had worried about, such as more insect damage or fungal diseases, did not materialize. Be sure not to make a thick, dense, layer of mulch that prevents air penetration into the soil as it can kill trees. I do not know just how thick that would need to be, but would presume a foot of packed, matted grass clippings would be dangerous for example. If you are using this method, we would like to hear how it is working for you.

By the way, a graduate student at Purdue University studied farming methods of early Mayans. He discovered that Mayan farmers spread banana leaves over the land to retain soil moisture and keep out competing weeds. Planting was done through individual holes dug through the banana-leaf mulch!

RICE HULL MULCH. Ralph Kusserow in Tanzania wrote with an interesting observation. Some of the beds were mulched with grass and some with rice hulls. He noticed that chickens did considerable damage in the beds mulched with grass but seldom bothered those mulched with rice hulls. He was intending to mulch everything with rice hulls the next time.

More recently he wrote, "The red glow on this paper is a reflection from my face." This year the chickens ravaged the beds mulched with rice hulls. He attributes the difference to the weather. "Last year was very dry and the mulch quickly formed a crust over the top. Although we have not had a large amount of rain this year, at the beginning of the season it rained at least a little almost every day for six weeks. That kept the rice hulls soft so that the crust did not form, making it easy for the chickens to scratch it. When the normal weather pattern returned, with a heavy rain followed by a week or so of sun with no rain, the crust formed and the chickens have not bothered coming into the garden at all."

He only noticed one problem with rice hull mulch. The crust that forms tends to cause water from a light rain or a watering can to run off. So he forms the rice hulls like a bowl around each plant to make watering easier. There was one other temporary problem. The light-colored mulch reflected the heat and made it hotter than usual. However within several days the mulch darkens, then both looks and feels better.