- Amaranth is a Drought-Resistant, Flavorful Green

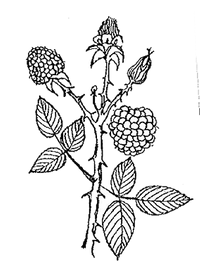

- Andean Blackberry

- Brazilian Spinach is a Good Source of Greens

- Bush Okra from ECHO Grew Well. How Do We Eat It?

- Cassava Leaves

- Carrot Emergence in Clay Soil

- High-Carotene Carrot Seed Available

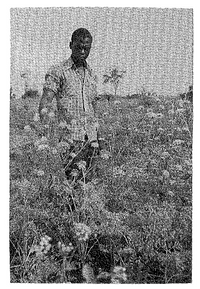

- Uberlandia Carrots Will Set Seed in the Tropics

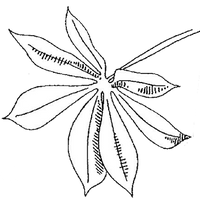

- Chaya is One of the Most Productive Leafy Vegetables and an Incredibly Resistant Plant

- Eggplant Pruning

- Grapes in Warmer Climates

- Jicama Tubers Might Be an Excellent Cash Crop for You to Consider

AMARANTH IS A DROUGHT-RESISTANT, FLAVORFUL GREEN. (Refer to Grain Crops for more information on amaranth seed.) Amaranths are cultivated worldwide as fast-growing, short-lived annuals. The leaves are high in calcium and iron. With their relatively high oxalic acid content, leaves should be boiled before eating. Some species can be weedy due to their high seed production, and leaf-eating caterpillars are a major pest. ECHO has many varieties of vegetable amaranths (mostly Amaranthus tricolor) which are favored for their leaves, although leaves of grain amaranths may also be eaten. We usually send two or three varieties when we receive a request, but if amaranth already grows in your area and you want to conduct a larger variety trial, specify that in your letter and we will send more.

ANDEAN BLACKBERRY. One of my fondest memories from Victor Wynne's farm in Haiti (at 6,000 feet) is the juice made from this Andean berry (Rubus glaucus, mora de castilla). It thrives on his farm, bearing over a very long season. Victor says  that it bears most of the year, although berries do not command a high price.

that it bears most of the year, although berries do not command a high price.

According to the book Lost Crops of the Incas, this blackberry is native from the southern highlands of Mexico to the northern Andes. It is widely cultivated in gardens in Ecuador and Colombia. "It is said to be superior in flavor and quality to most cultivated blackberries and raspberries. ...They are especially juicy and make excellent jam, which tastes like jam made from black raspberries."

This plant may be suitable for those working with peasant farmers at higher altitudes in the tropics. The plants are normally propagated by tip layers or stem pieces because they yield sooner, but they can also be started from seed. You must have the patience to baby the seed until it germinates. Victor says, "We kept our original seed continuously moist for at least two months before any seed germinated. Trays should be covered with some air-breathing transparent film to prevent drying out." They grow well on many kinds of soil. In well-tended plantings, annual yields are said to reach 20 tons per hectare.

ECHO does not have seed at present; we would like to receive some from our network in the Andean region.

BRAZILIAN SPINACH IS A GOOD SOURCE OF GREENS. Cory Thede in the Brazilian Amazon reports: "Brazilian Spinach (Alternanthera sissoo, also Samba lettuce, sissoo spinach) forms a thick ground cover. It creeps and roots from nodes over a large area. It responds well to fertilizer. A pest (centipede?) eats holes in the leaves at certain times of the year, but this only damages the appearance a bit. Once planted, it can be maintained permanently, as a perennial. Propagate it by  cuttings placed in the ground, with some shade (palm fronds for a week or two); it is very hardy, but keep it moist while rooting. It grows fast but is not invasive. Brazilians usually eat it raw in salads with oil/vinegar, tomato, and onion, although the literature recommends cooking it. This, together with lettuce and collards, are the most common greens in the area. In fact, it is better-liked than lettuce. Branches are sold in the market--pull leaves off the stems and eat the young vine tips.þ If you work in the humid tropics, ECHO can provide cuttings if you visit us in Florida or ship them to you just before you leave the States. The cuttings would not survive overseas mail.

cuttings placed in the ground, with some shade (palm fronds for a week or two); it is very hardy, but keep it moist while rooting. It grows fast but is not invasive. Brazilians usually eat it raw in salads with oil/vinegar, tomato, and onion, although the literature recommends cooking it. This, together with lettuce and collards, are the most common greens in the area. In fact, it is better-liked than lettuce. Branches are sold in the market--pull leaves off the stems and eat the young vine tips.þ If you work in the humid tropics, ECHO can provide cuttings if you visit us in Florida or ship them to you just before you leave the States. The cuttings would not survive overseas mail.

BUSH OKRA FROM ECHO GREW WELL. HOW DO WE EAT IT? Klaus Prinz wrote from Thailand, "We could not figure out how to eat the small pods. They ripened quite fast, though, so that a lot of seed was collected." Bush okra is a misleading name. It is actually grown for its leaves, which are cooked and eaten. It is called bush okra because its seed pods look a lot like very small okra pods. The scientific name is Corchorus olitorius, also called jute mallow and Egyptian spinach. It is a major source of food from the Middle East to Tropical Africa. The fibers are used in twine, cloth and burlap bags. The better vegetable varieties are smaller and more branched than those selected especially for fiber, but all have edible leaves. A related species, C. capsullaris, is the better known source of jute. The plants tolerate wide extremes of soil, are easy to grow and are resistant to drought and heat. Leaves may be dried for later use as a tea or cooked vegetable. They require little cooking. The leaves are mucilaginous (slimy), like okra, so may be offensive to some people. Plants reach over 3 feet (1 m) high and are about 20 inches (50 cm) in diameter. [The above information is from Frank Martin's Edible Leaves of the Tropics.] Want to give it a try? We have plenty of seed.

CASSAVA LEAVES. Cory Thede also mentions: "Brazilians also dry and powder cassava leaves and add them to foods--this is a very handy form of storage, especially for moms who don't want to leave the house to collect leaves during the cooking. Eating leaves is not too common a practice here, so maybe the powder disguises them well enough to be accepted, especially when used to enrich soups."

We asked David Kennedy with Leaf for Life for his perspective on using dried cassava leaves as a food, since cassava contains substances that produce hydrocyanic acid (HCN) when fresh leaves are eaten or pulverized. "HCN is a fairly common toxin in food. Cassava, lima beans, and sprouted sorghum have caused HCN poisonings. Acute HCN poisoning is quite rare. The minimum lethal dose is estimated at 0.5-3.5 mg per kg of body weight. So a child weighing 20 kg would need to consume between 10 and 70 mg of HCN. Ten grams of a low-HCN variety of dried cassava leaf would contain something like 0.08 mg. Chronic toxicity (also quite rare) has been reported mainly where there is a great dependence on cassava and a very low protein intake. Damage to the nervous system and especially the optic nerve can be caused by chronic exposure to HCN. Low consumption of proteins, especially sulfur-bearing amino acids, cigarette smoking, and air pollution all intensify the body's negative reaction to HCN.

"One would be tempted to steer clear of cassava leaves altogether to avoid any toxicity problems, except that the plant has several important attributes as a leaf crop, yielding large quantities of leaf that is high in dry matter, protein, and micronutrients...throughout the year in most locations. ...People are currently eating cassava leaves as a vegetable in much of Africa, and parts of Asia, and Latin America. I think the question is not whether to eat cassava leaves, but rather how to. Encouraging the use of low-HCN varieties is critical to this effort. A grinding technique that ruptures cell walls will dramatically increase the rate and total amount of HCN that disperses into the air. It is important that the leaves be ground when fresh, and quite well pulped, not just shredded. The loss of HCN is very dramatic then during drying." He sent us a Ministry of Agriculture publication from Brazil which showed the following HCN content for one variety (Cigana) of cassava: fresh--737 ppm; flour from a leaf dried whole-- 123.89 ppm; flour from a shredded leaf--75.58 ppm; and 33.60 ppm when dried after thorough pulping. The potential nutritional benefits of using leaves of this common and productive crop is considerable. (Refer to Food Science: Storage and Preservation. for more on this topic.)

"One would be tempted to steer clear of cassava leaves altogether to avoid any toxicity problems, except that the plant has several important attributes as a leaf crop, yielding large quantities of leaf that is high in dry matter, protein, and micronutrients...throughout the year in most locations. ...People are currently eating cassava leaves as a vegetable in much of Africa, and parts of Asia, and Latin America. I think the question is not whether to eat cassava leaves, but rather how to. Encouraging the use of low-HCN varieties is critical to this effort. A grinding technique that ruptures cell walls will dramatically increase the rate and total amount of HCN that disperses into the air. It is important that the leaves be ground when fresh, and quite well pulped, not just shredded. The loss of HCN is very dramatic then during drying." He sent us a Ministry of Agriculture publication from Brazil which showed the following HCN content for one variety (Cigana) of cassava: fresh--737 ppm; flour from a leaf dried whole-- 123.89 ppm; flour from a shredded leaf--75.58 ppm; and 33.60 ppm when dried after thorough pulping. The potential nutritional benefits of using leaves of this common and productive crop is considerable. (Refer to Food Science: Storage and Preservation. for more on this topic.)

CARROT EMERGENCE IN CLAY SOIL. (The following is taken from the July 1993 issue of HortIdeas.) Researchers in Brazil "tested various techniques to boost the emergence rate of carrot seedlings in heavy clay soil. Shading the seed bed worked better than mulching with organic materials such as sawdust and straw; adding a layer of sand resulted in poorer emergence than with bare soil." The HortIdeas editors add that they have "had no complaints about our stands of carrots since we began, several years back, covering the rows with boards until a high percentage of the seedlings break through the soil surface."

HIGH-CAROTENE CARROT SEED AVAILABLE. Dr. C.E. Peterson wrote, "It is generally agreed that vitamin A is the third most serious nutritional deficiency in the world, following total calories and protein. It is estimated that in four Asian countries 250,000 children become totally blind and many more partially blind each year due to vitamin A deficiency. ... Standard varieties of carrots have 80-100 ppm. The USDA hybrid A Plus has over 150 ppm." The Beta III carrot (not a hybrid) is a "market carrot" with a carotene content of 180-320 ppm. To give an idea for how much is needed, he said that one pound of an experimental variety that has 560 ppm would provide enough vitamin A for an adult for a month. "By comparison, the levels in some vegetables are: tomato 0.5 ppm, Chinese cabbage 23 ppm, kale or mustard greens 18 ppm." ECHO has trial packets of the A Plus and Beta III; if they grow well for you, you may order seed in quantity from commercial sources. Seed for the A Plus carrot may be available in bulk from Asgrow Seed Company, 4420A Bankers Circle, Doraville, GA 30360, USA; phone 800/234-1056, and Park Seed Co., Cokesbury Rd., Greenwood, SC 29647, USA; phone 800/845-3366. Order the Beta III from Asgrow as well. (If you have difficulty locating Beta III seed, contact Mr. E. Hansen in Kalamazoo, MI, USA, at phone 616/384-5545; fax 616/384-5647.)

Dr. P.W. Simon with the USDA at the University of Wisconsin wrote, "Vitamin A is necessary for normal vision and eye health, mucous membrane and skin health and disease resistance. A U.S. nutrition survey indicated that 40% of Spanish Americans, 20% of blacks and 10% of whites suffer from vitamin A deficiency. [It can cause] night blindness, permanent blindness and even death."

In developing countries, 90% of the vitamin A is typically from plants. The body converts carotene from the plants into vitamin A. Excess consumption of vitamin A itself is toxic, but the body regulates the carotene-to-vitamin A conversion so that toxic amounts of vitamin A are not produced, even when high amounts of carotene are consumed.

Here are some other interesting comments on carrots from Dr. Simon. Carrots tend to be less sweet if the nighttime  temperatures are high, if light intensity is low and if there is a lot of organic matter in the soil. Store under refrigeration or delay the harvest. Do not store in a sealed plastic bag, since they need to "breathe" and will spoil. Do not store carrots near apples or pears, as the ethylene gas that these fruits emit will cause the carrots to become bitter. Carotene is relatively stable during processing--between 5-20% of it is lost when canned.

temperatures are high, if light intensity is low and if there is a lot of organic matter in the soil. Store under refrigeration or delay the harvest. Do not store in a sealed plastic bag, since they need to "breathe" and will spoil. Do not store carrots near apples or pears, as the ethylene gas that these fruits emit will cause the carrots to become bitter. Carotene is relatively stable during processing--between 5-20% of it is lost when canned.

The Beta III carrot contains three times as much carotene as typical carrots. "To completely fulfill adult vitamin A needs with Beta III, 140 average sized roots (11 kg) would be required per person per year. This would require approximately one square meter of land." Dr. Simon says, "The major problem with the Beta III is its long thin 'imperator' shape, in contrast to the short broad roots grown everywhere else in the world but in the U.S.A." His present research is looking for the short, broad root shape and even higher carotene content. He is also looking into solving the difficult problem of carrot production in the lowland tropics. This brings us to another important topic: can you grow your own carrot seed?

UBERLANDIA CARROTS WILL SET SEED IN THE TROPICS. In the spring of 1992, William Tabeka wrote from Uganda. He wanted to grow carrots, but seed was not available. We sent information on the difficulties of producing carrot seed in the tropics. Carrots are biennials; they normally spend a winter dormant in the ground, then produce seed the second year. We also enclosed just a few seeds from a packet we had just received from Dr. Warwick Kerr in Brazil. He said that this carrot, called Uberlandia,' would set seed even in the tropics, and would do so in a single season.

Our interest in this carrot increased greatly when Mr. Tabeka sent us this picture of himself standing by what appeared to be carrots in full bloom. I wrote right away inquiring if that is indeed what I saw, and what he thought of the taste. He replied, "I assure you that the carrots really did put on seeds. The taste of the root is good and there is a difference, because that one which put on seeds has a root that is a bit longer than the others (some high carotene carrot seeds we had sent). There is no difference at all in the appearance of the seeds." A recent letter says he is now growing carrots from seeds that he harvested during the last rainy season.

Our interest in this carrot increased greatly when Mr. Tabeka sent us this picture of himself standing by what appeared to be carrots in full bloom. I wrote right away inquiring if that is indeed what I saw, and what he thought of the taste. He replied, "I assure you that the carrots really did put on seeds. The taste of the root is good and there is a difference, because that one which put on seeds has a root that is a bit longer than the others (some high carotene carrot seeds we had sent). There is no difference at all in the appearance of the seeds." A recent letter says he is now growing carrots from seeds that he harvested during the last rainy season.

We planted a few plots in the spring to produce seed for our seedbank. By early summer, they blossomed heavily and eventually produced seed. We need to work on timing to see if we can get seed during the dry season, as the heat and humidity of our rainy summers make it difficult to obtain high quality seed. Nonetheless, we can now offer our network seed with about 70% germination.

We allowed most plants to go to seed, so we have little information on size or taste of the roots (by the time seed was mature, the roots had shriveled up). I sampled two 3-inch carrots, trying them both raw and boiled. I prefer the varieties I am used to, but if they were the only carrots available, I would be glad to have them. In other trials, we found great variation in the plots, from commercial-sized, bright orange carrots to small yellow roots. Someone familiar with plant breeding could do a great service to the small farmer. Presumably a variety with superior qualities could be developed which would also still produce its own seed. ECHO has plenty of seed, and we continue to select better-quality carrots each year. If you try this seed, we will be VERY interested in your experience with and impressions of this carrot.

Dr. Kerr provided more information about these carrots. "Carrots do not usually flower in the tropics. Eighty years ago a group of Portuguese growers planted carrots from Portugal and the Madeira Island in the southernmost state of Brazil. Some of these plants flowered and produced seed. Plant breeders from Sao Paulo and Brasilia independently collected seeds and developed varieties called 'Tropics' and 'Brasilia.'

"I used these two in my work at the Federal Universities of Maranhao and, currently, of Uberlandia. For five generations I selected the best carrots using the following criteria: (1) size between 12-18 cm, (2) parallel sides, (3) red xylem, (4) resistance to local diseases, (5) late flowering, (6) no green on the top of the root. I call the resulting cultivar 'Uberlandia.' The vitamin A content (carotene) is between 9,000 and 11,000 I.U.

"It is advisable that people who grow the carrot in other areas carry out their own selection. Here is how to do it. After 90 days dig up all the carrots. Select the best 30 according to the above standards or standards of your own. Re-plant these carrots right away and allow to go to seed. The red xylem can be observed by cutting 3 cm of the inferior tip (narrow end) of the carrot. Discard if the xylem is yellow."

Dr. Kerr has made a great contribution to third world gardeners. In the USA, nearly all work by private industry and much of the work done at universities is for a hybrid so that people will need to purchase seeds each year and money will be available to fund research programs. We need more breeders working on seeds for the poor.

CHAYA IS ONE OF THE MOST PRODUCTIVE LEAFY VEGETABLES AND AN INCREDIBLY RESISTANT PLANT. Chaya, Cnidoscolus chayamansa, is native to the drier parts of Central America and Mexico, where it is grown in dooryards, often as a hedge. Consequently it has been no surprise to find that it is very resistant to drought. Ross Clemenger planted some cuttings in northern Colombia after visiting us. The weather turned so dry that he had to sell a lot of cattle for lack of forage. The chaya, however, flourished. What has been surprising is that chaya is equally resistant to our terribly hot, humid, rainy summers. In fifteen years neither disease nor insects have been a problem. The only things that have harmed our chaya are freezes and standing water. It will come back from the ground after a freeze, but is killed by a few days of standing water. Plants can reach 10 feet (3 m) in height and about 5 feet (1.7 m) in diameter.

The young leaves are used to wrap tamales or are eaten with the thick terminal stems cooked as greens. They have a firmer texture than most greens I have eaten. If people in your area eat greens, I think they would likely develop a taste for chaya. For example, an American friend who married a Mexican woman has become quite fond of chaya, and says they like to serve it at least twice weekly. Another friend of Chinese descent is enthusiastic when we take her a bag of chaya leaves, even though it is not a plant she had in China.

Chaya is one of the most valuable green leafy vegetables. It was among the "underexploited" food plants popularized by the  National Academy of Sciences. Leaves are reportedly high in protein, calcium, iron, carotene and A, C, and B vitamins. One consideration with chaya is that it should not be eaten raw. It contains cyanogenic glycosides, which can lead to cyanide poisoning. These are inactivated and released as a gas by frying or boiling for 5 minutes. (We discard the cooking water, but that is not essential.) Brief stir-frying is not adequate cooking.

National Academy of Sciences. Leaves are reportedly high in protein, calcium, iron, carotene and A, C, and B vitamins. One consideration with chaya is that it should not be eaten raw. It contains cyanogenic glycosides, which can lead to cyanide poisoning. These are inactivated and released as a gas by frying or boiling for 5 minutes. (We discard the cooking water, but that is not essential.) Brief stir-frying is not adequate cooking.

If you work in Central America, you may have heard of Chaya brava in your area. The leaf petioles and stems of this variety contain tiny stinging hairs which make it necessary to wear gloves when harvesting the leaves. Some have brushed against the plant with their bare skin and were left with a red rash. Please note that ECHO now has a non-stinging variety (mansa) available for distribution. If stinging chaya grows in your region, it may be difficult to convince people to harvest and eat it. People who ordered chaya from ECHO before 1990 received a variety with a few stinging hairs; if it was successful, you might want to order this one which is from Belize.

Chaya is easily propagated by cuttings. Though it is frequently in bloom, it almost never sets seed--a quality which nearly eliminates its weed potential. Fortunately, because it is so resistant to dry weather, we can get live cuttings to you. We did a simulated tropical mailing. Several packages of chaya cuttings, prepared in different ways, were left in our hot workshop during the summer to simulate delayed overseas delivery. They were then removed at 1-4 week intervals and planted. We had good results at up to three weeks, and some survived after four weeks. We sent a package to Asia which was received 10 days later. They trimmed the bottoms and placed the cuttings in fresh coconut milk. In half an hour the surviving small leaflets had regained turgidity. Several cuttings survived. (Some of the edible hibiscus cuttings also survived the trip, so perhaps we can begin sending those as well.) We sent some cuttings in a regular envelope to Dr. Warwick Kerr in Brazil. He now distributes cuttings in the local church and reports that his family eats them at least twice a week.

Arkhit Pradhan in India wrote, "Chaya is all over now from your original cuttings. It's in maybe thirty villages in the hills. People have found it will grow when other greens are not coming through with the rains--strange plant."

If you want to try chaya in your area and think a small airmail package can reach you in three weeks, we will send you a few cuttings. This will cost us a few dollars in postage, so please only order if you will promptly care for the cuttings. Water the soil moderately but do not keep overly wet while cuttings are starting.

Cory Thede in Santarem, Brazil, writes: "Chaya is iguana-proof! Leaves are within their reach, but they don't touch them. Though it is exceptionally productive in some parts of the world, it grew erratically here--I think a dry-season mite stunted its growth. I did not see much use being made of it in this area.

"Propagate chaya by OLD (grey, not green) thin stalks if they are to be transported, as these have less pith and weight. (For immediate planting, any part will do.) When it arrives, cut off any rotting parts but you probably do not need to make new cuts if it is healing well. Be sure to plant it right side up, so leaf scars look like smiles not frowns. The bud is above the leaf scar. Leaves are flavorful when cooked with ham, onion, salt, and pepper." [Ed: I prefer them with salt and vinegar.]

EGGPLANT PRUNING. Warwick Kerr, head of the biology department at the Universidad Federal do Maranhao in Brazil, prunes his eggplants and African eggplants. The second crop (the farmers call it the "second life") is 30% greater than the first in spite of the death of 10-15% of the plants after pruning. Here is how he does it. When each eggplant has produced 20-30 fruits and the plantation looks old, he cuts the plants at a height of 30 cm, then removes the cut branches from the garden as far as possible or burns them. Finally he applies chicken manure, his cheapest fertilizer, irrigates and sprays the stalks with insecticide and fungicide. All plants that happened to acquire a virus usually die upon pruning, so he collects his seed from the second crop.

GRAPES IN WARMER CLIMATES. The following excerpt on grapes is taken from an article by Rick Parkhurst in the California Rare Fruit Growers newsletter (1981 #2). "For a long time it has been known that the 'wound effect' can replace the cold requirement in grapes. This means that the plant is pruned very severely every year. In the tropics more than 90% of the previous season's growth is removed by pruning. This severe cutting back helps the plant to break the rest period. When the fruit is harvested the plant is pruned. In three or four weeks, new growth appears and in three or four months new fruits ripen. The grapes in the tropics give two regular crops each year. Once this principle was realized, grape-growing spread throughout India, Thailand and other tropical countries."

Some additional information comes from a one-page response to a question on grapes that I found in VITA's files called "Grape Vine Management in the Tropics." "Grape vine management in the tropics is a problem: vines tend to be short-lived, produce small crops, and require special care. Grapes like a period with temperatures below 0øC. Attempts in the tropics have not been very successful; plants continuously grow, produce clusters, rebud, remain evergreen, and eventually burn out. However, there are tricks that have been developed for use under dry tropical conditions to simulate a dormancy period. If the vine is forced into two growth cycles, one in the wet season and the other in the dry season, it will produce. By pruning at the beginning of the wet season, a growth cycle is initiated in which a small crop may result. Following this, the vine is pruned again to induce another cycle of growth. It is during the dry season that the main crop results in quality grapes. Irrigation is used in conjunction with pruning to assist the plant during this cycle. (It is a very common practice to leave too much wood on the plants when pruning and this causes poor quality and premature burn-out of plants). In the dry warm climates of Peru, India and places in Brazil, [the dry season has] simulated a dormancy period." James Smith reports that he ate excellent grapes in the mountains of Cameroon. Grapes are now a commercial crop at a winery just a few miles from ECHO, where most years we have no freezing temperatures.

Muscadine grapes are native to Florida and do not require much cold. They grow as single berries rather than in bunches, and they are very resistant to pests and diseases. Most muscadines are eaten fresh. ECHO has fact sheets on muscadine grapes from the University of Florida for those who are interested.

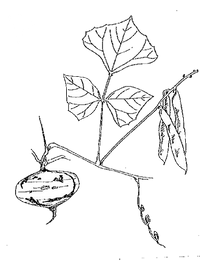

JICAMA (PACHYRHIZUS EROSUS) TUBERS MIGHT BE AN EXCELLENT CASH CROP FOR YOU TO CONSIDER. Of  the many new food crops that we have tried at ECHO, I consider this the one above all that should be added to most Florida gardens. For many of you, it is already an important food crop, but others have never heard of it. This is a common trait of the "underexploited" food plants that are in our seed bank. Most of them are familiar to and liked by at least some of our readers. Very few are wild "weeds" that are being promoted for the first time as food. I will list some of the common names to help you decide whether you already know this plant: jicama (Mexico and the United States), yam bean (not the African yam bean), ahipa (S. America), dolique tubereux or pais patate (French), fan-ko (Chinese), sankalu (India), or sinkamas (Philippines).

the many new food crops that we have tried at ECHO, I consider this the one above all that should be added to most Florida gardens. For many of you, it is already an important food crop, but others have never heard of it. This is a common trait of the "underexploited" food plants that are in our seed bank. Most of them are familiar to and liked by at least some of our readers. Very few are wild "weeds" that are being promoted for the first time as food. I will list some of the common names to help you decide whether you already know this plant: jicama (Mexico and the United States), yam bean (not the African yam bean), ahipa (S. America), dolique tubereux or pais patate (French), fan-ko (Chinese), sankalu (India), or sinkamas (Philippines).

Jicama is a leguminous vine grown for its edible tuber. The most unique feature of this tuber is that it remains crunchy after cooking. For that reason it can be used in any recipe that calls for water chestnuts. In a local supermarket we can buy water chestnuts for about $8 per pound. A 5 x 12 ft. raised bed could probably grow 25 pounds of jicama easily. It retails locally at 75 cents per pound. To the North American tastes of my wife Bonnie and me, recipes lose nothing by making the substitution. We felt like rich folks during the jicama season, adding jicama extravagantly to water chestnut recipes. It was even the hit of a fondue dinner that we served. Slices of the tuber are eaten raw in salads or with chili pepper and lemon juice, or another dip.

Tuberous root development is initiated by short days. We have planted seed at several times of the year here at ECHO in SW Florida. Regardless of planting date, tubers were not formed until days became very short, around December. For this reason, it is unlikely that jicama can be grown commercially in the USA except in southern Florida and perhaps southern Texas. For maximum size the tubers were usually harvested in January and February. Vines planted in early spring were so vigorous by the time short days gave the signal to produce tubers that very large, distorted tubers burst from the ground. Tubers from seeds planted in May and June had the best combination of large size and good appearance. Seeds planted in August gave apple size tubers, though the taste and crispness were superior.

The following paragraph is excerpted from the National Academy of Sciences book Tropical Legumes: Resources for the Future. Jicama is among the most vigorous-growing legumes. It has coarse, hairy, climbing vines that can reach 5 m long. Although they grow well in locations ranging from subtropical to tropical and dry to wet, for good yields they require a hot climate with moderate rainfall. They tolerate some drought but are sensitive to frost. When plants are propagated from seed, 5-9 warm months are needed to produce larger tubers, but propagating from small tubers greatly reduces the growing time (to as little as 3 months in Mexico). Flowers are sometimes plucked by hand, doubling the yield. [I found no difference in yield in a simple trial in which I picked flowers from half of a small plot. Tubers appear to form only as days become shorter.] Yields average 40-50 t/ha in Mexico's Bajio region. Experimental plots have yielded 80 or 90 t/ha. The tubers contain 3-5 times the protein of such root crops as cassava, potato, sweet potato and taro. However, the proportion of solids in fresh jicama in only about half that of other tubers because of the high moisture content.

All of the above-ground parts of the plant contain the insecticide rotenone. I would not recommend eating the pods, although immature pods are reportedly eaten at a certain stage in the Philippines. Much of the above- ground portion of the plant can be used as an insecticide, although there are plants better suited to this preparation (such as Tephrosia). One report from scientists in Senegal suggests crushing 2 kg of mature seed into a fine powder and mixing with 400 liters of water. After one day, finely strain the mixture to remove all the seed matter, then apply to plants to protect from a variety of insect pests.

We would like to hear from you if you have experience with jicama in any of three areas. (1) Can the foliage be fed to rabbits, cattle, goats or other animals? (2) Do people use it as an insecticide and, if so, how do they prepare and apply it? (3) If there are special varieties that you think might be of interest to us and others and you can send us some seed to get started, let us know and we will send you a plant import permit. If you would like to try growing jicama and seed is not available in your country, write us for a small packet of free seed.