Introduction

Church-based missions and other small non-government organizations (in this paper referred to together as ‘NGOs’) are doing some of the most effective and sustainable agriculture and food security work in developing countries. NGOs are able to innovate and include a package or menu of community options in villages in rural areas. They can be responsive to the interests of communities, and can promote a sustainable model of rural poultry vaccination— sometimes more effectively than the district or local government alone.

What does a typical model of a sustainable Newcastle disease (ND) control program consist of for rural poultry keepers?

The model and how it operates

The NGO involves the local government authorities in the vaccination program. An NGO works with district and village leadership to either raise awareness or respond to a known need for ND control. The NGO agrees to conduct a village meeting with a representative of the district to confirm with villagers their experience of death loss to ND, ascertaining which season of the year it is more prevalent in their experience, and raising interest in a solution. At the same meeting, the model described below (the concept of rural vaccinators administering a service to their neighbors three times per year with cost-recovery) is shared with the community members. At the end of this village meeting, individuals may be identified who best fit the criteria for community vaccinators (explained during the meeting), and they may be selected for subsequent training.

District extension officers are engaged in partnership to prepare the community and to participate in selecting, supervising, monitoring and reporting on the activities of community vaccinators to the NGO and the district. Ideal qualifications and roles of district extension staff include the following:

- Technical know-how (Certificate or Diploma) in general agriculture

- Prepared to collaborate with NGOs in agricultural development programs

- Willingness to promote an integrated support effort among caregivers in the initiative

- Scope for integration of rural poultry vaccination in their working situation

- Prepared to learn and disseminate new initiatives in food security

- Prepared to assist other stakeholders by follow-up and linking actors together.

This initiative is about empowerment. Community vaccinators will be selected, trained, and mobilized to assist their neighbors. Community vaccinators in other initiatives have proven to greatly enhance the adoption by community members of wider innovations. For example, they have significantly reduced the number of cases of other poultry diseases in the community, increased the adoption rate of simple poultry innovations, and helped to target needy participants who could benefit from initiative interventions.

Ideally, at the same time that community vaccinators are being mobilized, a community food security committee is formed among community leaders and existing groups. This committee supports dissemination of interventions by increasing cohesion of sub-groups and promoting wider participation. Strong participation by local village leadership in selection, training and follow-up helps encourage group members to remain active or be replaced. The committees may vary in size and activities according to their interest, but are generally comprised of four or five members chosen based upon their ability to carry out the following:

- Mobilize selection of appropriate groups within the community for training

- Identify and supervise potential rural caregivers from sub-villages

- Ensure community cooperation so that families pay for animal vaccinations

- Ensure the welfare of more vulnerable households through participation, sharing and caring among members and their families–making visits to households

- Assist in preparation for trainers (e.g., alerting community, arranging a venue for meetings, food)

- Help with other activities, as appropriate (e.g., mobilize home-based care by caregivers, support of HIV+ groups)

- Assist coordination of field days and agriculture shows

- Address environmental issues (e.g., sanitation, tree planting, etc.)

- Provide accountability for equipment (e.g., bicycles) used by community vaccinators

- Share progress reports and productivity records with other village leaders

- Identify and address constraints (e.g., potential markets, sources of micro-finance, or agriculture inputs for group members).

Community vaccinators are chosen by the village government. To meet the selection criteria, they must:

- Be willing to cooperate with the village government

- Reside in or near the respective community

- Be available to undertake regular campaigns

- Be willing to record their work activities and spending (including receipts)

- Commit to provide services on time, by a set calendar

- Agree to and obtain a fair fee for services rendered (contract with village authorities)

- A minimum of 50% of the vaccinators must be women.

Community vaccinators receive a one-week-long orientation training, and are accompanied on their first vaccinations. During this orientation week, community vaccinators are trained in areas related to animal health, with special emphasis on vaccination. In the early mornings, they apply the simple vaccination skills that they have learned by vaccinating farmers’ chickens on dates previously agreed upon in the larger community assembly.

A fee should ideally be charged for the first round of vaccination, unless the NGO is concerned that the charge will discourage participation to the extent that the benefit of the vaccine is less obvious, slowing its adoption. If subsidized the first time, be sure to emphasize that subsequent vaccinations will need to be paid for to cover the costs of vaccines and the community vaccinators’ time. Thereafter, community vaccinators are encouraged to buy vaccines and vaccinate chickens on a for-profit basis, with farmers paying for the vaccination.

In Tanzania, for example, community vaccinators buy vaccines for approximately $6 per vial of 400 doses, or the equivalent of $0.015 per dose. However, the community vaccinator should charge up to $0.10 for each chicken vaccinated, as agreed in the community meeting (the same dose—one drop—is given to each bird, whether a small chick or a mature cockerel). At this price, a community vaccinator earns almost $35 profit from one vial, making it worthwhile to canvas and service the homesteads in her area for three or four days.

Follow-up is as important as mobilizing community vaccinators and food security committees. NGO trainings and mobilization of local farmer groups should be supported with the assistance of district extension staff. This link with the local government, at the district level, ensures a level of sustainability and preparedness for scaling up successful programs. The district staff gathers vaccination data from community vaccinators and submits progress reports (e.g., number of chickens vaccinated in a given period of time). If the NGO can manage, bicycles may be provided to well-performing community vaccinators, to facilitate their movements in the villages. District staff members may receive a small stipend each quarter as appreciation for their involvement in the program.

Sustainability of the model

To a large extent, the model has been found to be successful and sustainable. The success of the model is owed to the following factors.

- Profitability to the community vaccinators.

Community vaccinators derive profit out of this venture; the better performers are also provided with bicycles as an additional incentive to them. As a result, they are able to conduct vaccination as a business and as a means of livelihood.

2. Involvement and motivation of the

district staff. The NGO ensures the support of district staff and local leaders by involving them in the vaccination program. Local leaders are involved in mobilizing farmers. Also some members of the community households are nominated into the Community Food Security Committee (CFSC). The district staff monitors and supervises the activities and reports to the NGO. To provide motivation, the district staff is given some stipend upon submission of a report to the NGO.

3. A three-way reporting structure.

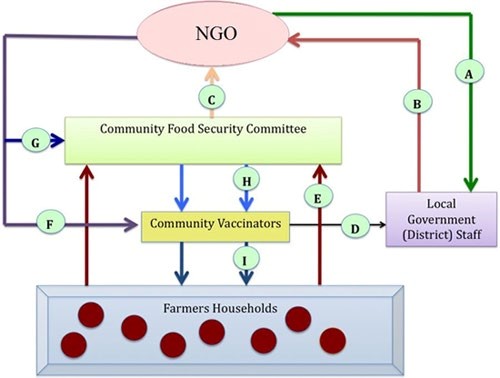

Farmer households report to the CFSC (as indicated by arrow D). The CFSC reports to the NGO (as indicated by arrow C), and district staff reports to the NGO (as indicated by arrow B). The three-way reporting structure helps to ensure reliability of information, as the NGO is able to cross- check by comparing the two reports, then can clarify deviations and reasons for deviations.

Limitations of the model

The NGO has to coordinate among the local government staff (arrow A), the CFSC (arrow G) and community vaccinators (arrow F), a process that can be tedious and time consuming, especially in the initial stages, before all are equipped with transport and a routine is established. However, if they have been well-trained, vaccinators with community oversight can continue to ensure service provision after the NGO withdraws support in two or three years.

Case Study: Healthy Chickens Increase Villagers’ Prosperity

Naisula Estomiy is a 36-year-old mother of two living in Olkereyan village on the outskirts of Arusha in Tanzania. In June 2009, Naisula joined a village group to attend a poultry production training session with Global Service Corps–Tanzania (GSC-TZ). Based on Naisula’s intelligent questions and lively participation, Naisula was selected by others in her group to attend a special training to become a community chicken vaccinator. She learned how to vaccinate chickens as a small business on behalf of the group and the wider community.

With support from her village extension officer, she set up a regular schedule of chicken vaccination events in her sub-village to protect the birds from ND. Before the vaccination program, villagers were unwilling to invest much in raising chickens, since most of them died from ND. People rarely provided food for their chickens, and instead left them to scavenge for food. Naisula learned how to apply the simple eye-drop vaccine to all chickens, whatever their ages, at a cost per vaccination of only 50 shillings (USD $0.03).

The vaccination program has significantly lowered chicken losses. In 48 villages where GSC-TZ has trained community vaccinators, poultry keepers now experience higher yields. Naisula has increased her flock by 700% to 90 chickens, and collects 25 eggs per day (as compared to the pre-vaccination time when a whole week often passed with no egg collection.) Naisula is also able to collect a small fee for her vaccination rounds (which reached 3,000 chickens every fourth month), which provides an income of Tsh 150,000 (US$100) for one week of work each round. Recently, she paid for a wire mesh perimeter fence to confine her growing chicken flock within her yard. The increased income from bird and egg sales has meant she can afford school fees for her two children and more food for her family.

Cite as:

Broughton, T. and E. Kinsey 2013. Engaging Non-Governmental Organizations in Newcastle Disease Control. ECHO Development Notes no. 118