This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 32.

Key Ideas:

• Potatoes can produce a lot of protein and other needed nutrients.

• They are difficult to grow in the tropics due to the hot climate.

• New varieties are available for the tropics.

• Inexpensive and efficient multiplication methods for producing the starting material are needed.

• New methods of multiplication are being tested

Summary

Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum) contain high-quality food properties and are very good protein and energy sources on a daily per hectare basis of production (Frusciante et al. 2000). Potatoes are grown mostly in cool climate areas. In the tropics, they easily suffer from several diff erent kinds of stress related to hot climate, which sometimes ends up causing problems such as attacks of fungal diseases. New potato varieties that arebetter adapted to hot climates could enable development of potato production in the tropics and could potentially provide livelihood opportunities for small-scale farmers. However, providing enough stock material to meet the potential need could be challenging.

Micropropagation is an efficient method to rejuvenate and multiply potato plant materials. It is mostly used to multiply disease-free seed potatoes. Often, only cuttings from juvenile plants can be rooted; this ability is lost when plants get older and they reach maturity. Rejuvenation is needed to multiply plant material efficiently. However, the micropropagation method is typically very expensive and requires highly educated personnel. If a method to rejuvenate potatoes was affordable and accessible to NGOworkers, communities, and farmers, rapid adoption of new potato varieties for the tropics could result, adding another tool to the toolbox in the quest for food security. Here, we share about one such low-cost method that was successfully studied and that appears to have great potential.

Definitions

Juvenility is the plant stage from germination to early flower production. When a juvenile plant moves to the adult stage, it passes through what is called a “phase change.” Flowering is not possible until this change has occurred. Juvenile plants have some unique characteristics that often do not appear in mature plants; perhaps the most economically important characteristic is the ability of cuttings from juvenile plants to form roots. Many mature plants partially or totally lose this ability, while young plants root easily from diff erent kinds of cuttings.

Micropropagation is the practice of rapidly multiplying plant material to produce a large number of off spring plants, usually using modern plant tissue culture methods. Micropropagation is often conducted using tissue culture and other specialized techniques, which require sterile environments, growth chambers, media, and other expensive inputs.

Rejuvenation is the opposite of maturation and ageing. The rejuvenation process can take place naturally by sexual seed reproduction (when a plant’s flower is fertilized and creates a seed) or with human involvement by the use of micropropagation or stem cuttings.

Potato Production is most often done by planting mature potato tubers (the thickened underground stem/storage organs) from seed potatoes; the resulting potato plants will be clones of the mother plant and will form genetically identical tubers. Potato tubers are considered physiologically mature, so the resulting cloned plants will not pass through a juvenile stage. Plants grown from potato seeds, which would pass through a juvenile stage, have unpredictable characteristics and are not very useful for commercial production of potatoes.

Micropropagation is most commonly used to rejuvenate mature potato material while retaining the desired genetic information. However, it is a very expensive method to multiply plant materials. The study described in this article was done to determine if a low-cost, low-input method to clone and rejuvenate potato varieties could be used in the tropics, to introduce new genetic material and potato varieties.

Materials and Methods

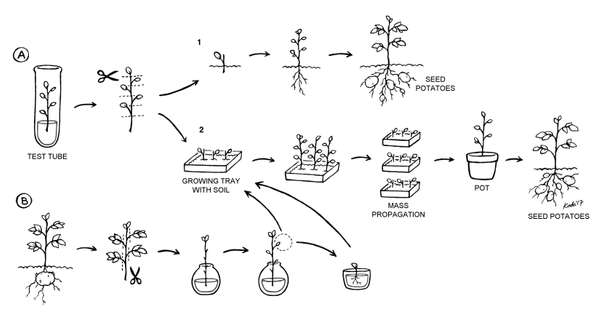

Two code-named potato varieties (PO7 and PO3) received by Professor Hong’s team from Vietnam were tested for production and productivity in Cambodia. We used a few shoots grown via micropropagation from a tissue culture vial, and some tubergrown shoots, to test two low-cost mass propagation techniques (Figure 1, page 1). These techniques, although used in the current study only on the two code-named potato varieties, could be used on most other varieties of potatoes. This experiment utilized new varieties of potatoes from Vietnam and occurred in a regular offi ce in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Plants were placed near a window to receive indirect natural light; two desk lamps provided extra light and were used to provide a 16-hour photoperiod (Figure 2). Small cuttings were grown at temperatures between 23 and 36°C. Further growth and part of the single-leaf rooting experiment took place outdoors under normal Cambodian climatic conditions.

Two different methods were employed to ascertain whether a small amount of new potato stock could be multiplied under conditions likely to be encountered in the tropics (Figure 1, page 1). The first technique utilized one-leaf cuttings taken from tissue culture starter plants (Figure 1A; Figure 3). These one-leaf cuttings were kept moist until they were planted in soil in a moist tray (Figure 2A2; Figure 4). They were left to grow until roots were initiated and the tiny plants had grown several new leaves. At that point, each small plant could yield more one-leaf cuttings, initiating mass propagation. Alternatively, these one-leaf plantlets could theoretically have been planted out into the field and cultivated to seed potato production (Figure 1A1). In both cases, seed potatoes would result, with tubers that could then be cut and planted for further potato production.

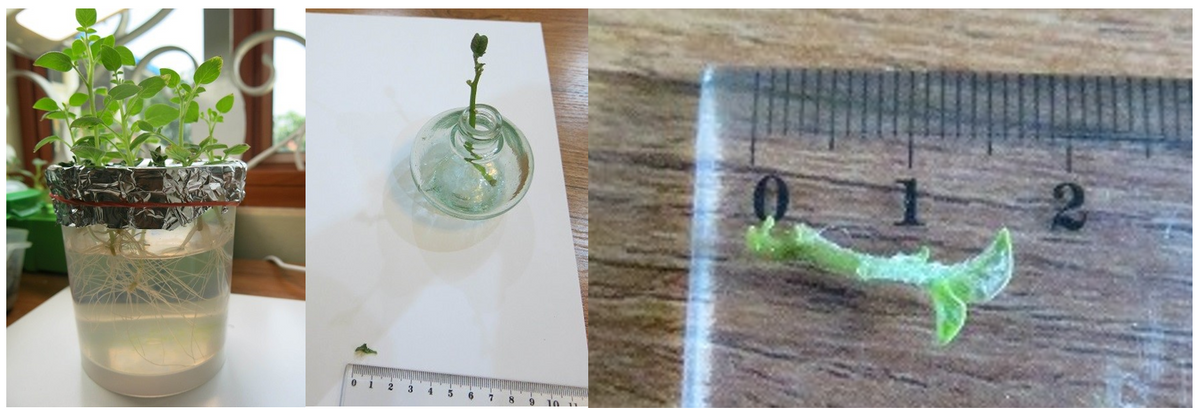

To improve the rooting process and hasten it, we tried also tucking the plants through holes in aluminium foil over a cup of water in order to help to reduce evaporation and increase humidity around the roots (Figure 5). In water, they produced primary roots in four days (Figure 6). When left for a longer time in the water, the original one-leaf cuttings grew longer shoots with several new leaves and developed substantial primary and secondary roots (Figure 7).

Older, larger cuttings from mature tubergrown plants can also be used to rejuvenate and propagate potato plants (Figure 1B). In this experiment, cuttings were also taken from tuber-grown plants. All but the top leaves were removed. Then, the cuttings were placed in water and left in the same conditions as the technique above (Figure 8). Small side shoots (0.8-1.2 cm) of these cuttings became the stock material for rooting new rejuvenated plants (Figure 9).

The rooting process of the original mature cuttings was very slow, and we did not end up planting these cuttings from tubergrown plants. Instead, minor side shoots grown during the water-rooting stage were removed and rooted in soil (Figure 1B). Shoots from 1.2 to 1.8 cm long (Figure 9) quickly formed primary roots when covered with small plastic cups to help maintain humidity (Figure 10).

Once established, the tiny plants from any of the three kinds of cuttings (direct planting one-leaf cutting in soil, one-leaf cuttings first rooted in water and then transplanted in soil, and small side shoot cuttings from mature cuttings in water) started to perform like the shoots from the first micropropagation technique, and could be utilized for mass propagation to create seed potatoes (Figure 11).

Results and Discussion

The one-leaf cuttings rooted and grew as consistently as in previous experiments (Haapala, 2004; Haapala 2005; Haapala et al. 2008). Direct rooting was more difficult in Cambodia than in Finland (where this experiment had been conducted in the past) due to the extreme tropical weather conditions. “Mini-greenhouses” (i.e. transparent cups placed over the planted cuttings), the us of aluminium foil over water, and some plastic covers over the new transplants made the work more successful.

The small plants that were being rooted in soil using the methods above were sensitive to root neck diseases, presumably from a fungus. Watering underneath the soil tray clearly helped with the problem.

Small side shoots (Figure 9) from the tuber-grown cuttings (Figure 8) rooted well under small plastic cups. As they grew, they started to perform like the other shoots originally from micropropagation. Leaves from juvenile potato plants look very different from leaves from mature plants, so we assumed that the plant material during the two rooting stages was rejuvenated and could be used for mass-propagation. Cuttings taken from shoots of originally mature material did not diff er from the other rooted one-leaf cuttings.

Conclusions

Propagation via one-leaf cuttings can be a low-cost and effi cient multiplication method for new varieties of potatoes meant for the tropics, enabling the creation of many plants from a small starting population. The rejuvenation process is usually done through micropropagation in a sterile environment, but we have shown that it can be done in a normal office space in the tropics by using tissue culture material or small side shoots taken from mature cuttings of tuber potatoes.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful for Professor Hong (Figure 12) and his team at the RUA for the good cooperation during the last three years.

References

Frusciante, L., A. Barone, D. Carputo, M. R. Ercolano, F. della Rocca, and S. Esposito. 2000. Evaluation and use of plant biodiversity for food and pharmaceuticals. Fitoterapia 71:66-72.

Haapala, T. 2005. Use of single-leaf cuttings of potato for effi cient mass propagation. Potato Research 48: 201-214.

Haapala, T. 2004. Establishment and use of juvenility for plant propagation in sterile and non-sterile conditions. Academic dissertation.

University of Helsinki, Department of Applied Biology. Publication no. 21. Available: http://ethesis.helsinki.fi /.

Haapala, T., R. Cortbaoui, and E. Chujoy. 2008. Production of disease-free seed tubers. A simple, low-cost technology can help developing countries produce the healthy seed tubers farmers need for sustainable potato production. FAO Factsheets. Available:http://www.potato2008.org/en/potato/seedtubers.html