Introduction

This ECHO Best Practice Note distills insights from farmers and other specialists who collaborated in promoting livestock as a means to improve rural livelihoods. Acknowledgment is given especially to Heifer International [heifer.org/] and to all its partners who developed a substantial program that still impacts thousands of families.

Historical background

Figure 1. Recipient of an animal from a rural livestock project. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Having worked for over 45 years in rural development, much of that time promoting livestock projects in East Africa, the author shares lessons learned and emphasizes the need to continue learning from others. He helped Heifer International pioneer livestock projects with smallholder farmers in collaboration with government staff and local Non-Government Organizations (NGOs) in villages throughout Tanzania, aiming to assist needy families.

Projects were not successful at first. Initial efforts focused on collective village livestock farms in Ujamaa villages in the 1970s, a policy developed under President Julius Nyerere in which farming in rural areas was encouraged by the collective initiative of villagers. The lack of a sense of ownership of the collectively owned animals led to many losses. For more complete historical background about livestock in Tanzania in specific, see Annex 1. After a few years, the work shifted to assisting individual families with livestock, enabling many to break out of the poverty cycle.

Later, more successful projects had profound impacts on households, and the concept of farmer-implemented livestock improvement spread rapidly throughout East Africa. These projects usually entailed the introduction of ”improved” livestock (often meaning exotic, higher producing livestock) in the hands of individual farmers/pastoralists whose communities, in turn acted as centers for village-based breeding and demonstration of improved livestock management. Animals provided by the project were a source of informal rural credit that benefited families who otherwise would not qualify for bank loans (Figure 1). A pass-on loan approach was used in which, families that received livestock signed an agreement with village committees to return the first female and another third offspring or more, and to pass their training onto their neighboring project farmers/pastoralists so that other needy families benefitted and expanded the impact of the projects. Thus, recipients maintained their dignity by also being able to help others.

Training of farmers and pastoralists featured the integration of farming technologies with a wide variety of livestock: dairy cattle, dairy goats, fish, bees, poultry, camels, indigenous livestock, and integrated farming technologies The scope of work diversified to include more sustainable and integrated approaches over time including agroforestry, soil conservation, agroecology, processing, marketing, and formal rural credit.

Principles

The importance of ownership and commitment

In the early 1970s, Heifer International embarked on a large livestock project in collaboration with the Tanzanian government and bilateral donors by investing in a government breeding farm that had considerable assistance from international loaning agencies. At the same time, other bilateral donors were recruited to start up large government breeding farms to produce crossbred dairy heifers for distribution in the country. Subsequently, offspring from the original foundation herds were to be provided to village collective farms, which local leaders were given responsibility to manage. It soon became apparent that, with both the government breeding farms and the collective village farms, there was a lack of sense of ownership of the livestock and attention to detail. This lack of ownership resulted in high numbers of livestock deaths from shirking responsibilities and lack of commitment. The breeding farms needed a large number of offspring to maintain their own numbers, so few livestock were available for distribution. While this assistance was not a total loss, it taught hard lessons an important one being that livestock projects need a high level of personal commitment and attention to detail in order to succeed.

Why not breeding stations?

Early on, the assumption was that breeding farms were needed to multiply improved animals for distribution to farmers. Breeding farms require large capital investment and they often suffer from a lack of commitment or motivation by the staff who operate them. By investing in smallholder farmers instead, through training and a contract system to pass on offspring to new farm families under local project committee supervision, projects act as a nucleus of breeding animals, one animal per family. In these village-based breeding farms, all products —including manure, meat, milk, and money— generated from livestock became the property of the family. This significantly reduces overhead costs breeding centers incur and smallholder farmers are effective multipliers of offspring.

Why not monetary credit versus livestock credit?

In the late 1970s different projects were begun simultaneously by banks, bilateral agencies, and faith-based institutions in Tanzania to try to assist smallholder farmers embarking in dairy farming. Soon they found that by using formal bank credit, only well-off farmers who demonstrated collateral could access loans, and these farmers often did not need the credit. Formal credit institutions shied away from supporting low-income farmers. By contrast, the informal pass-on loan projects issued contracts for pass-on offspring to cover the risk of loaning livestock. This more effectively reached families which, though needy, were capable of preparing and caring for livestock when overseen by village committees. Smallholder farmers were able to repay the loans with livestock they produced. See Annex 2 for more information about formalizing cash credit systems.

| Similar lessons were learned through an initial project started by a church diocese that had obtained a farm to use as a breeding center. Through a political maneuver, the farm was taken away from the church by the village government. In order not to lose all the animals, the church quickly removed the movable assets, including the cattle, and dispersed them among targeted needy villagers nearby. The animals were kept inside their houses for lack of time and adequate preparations, but they were cherished and survived. Slowly, the livestock increased the nutrition and incomes of the families. The sense of ownership created a great sense of responsibility and pride, and passing on a calf to a new family was a surprisingly successful way to expand the project despite meager training in proper husbandry. As time passed, better training, infrastructures, and health care were adhered to. As the church improved each of these aspects over time, the projects enjoyed high survival of offspring, rapid expansion, reasonable production, and effective paybacks. This pilot project became a learning center for over 100 other projects which were supported throughout Tanzania, and the concept spread rapidly across East Africa in neighboring Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda with ‘heifer projects’ sprouting by numerous donors. |

Practices

An Effective Programming/Model

Pass-on livestock projects that require passing on the gift with contracts supervised by local committees are highly impactful

The author’s experience affirms that livestock are indeed a beneficial part of most agricultural systems, contrary to some modern theories of their obsolescence. I am not referring here to factory-farming but rather to animal raising by smallholder farmers and small-herd pastoralism. Livestock keeping by smallholder farmers and pastoralists, though very different, generally can add value, nutrition, and income diversification to low-income homesteads as well as bolster a viable rural credit program. Passing female offspring on to other resource-limited families, with good local supervision in the selection and preparation of the recipients, has proven successful and creates a local livestock production system. As one livestock officer commented,

“Other organizations lend cash to resource-poor people who are under great pressure and demands. In many cases, little of the money will be able to go into the intended plan or goal. Then they cannot pay back the loan, and they will have their collateral taken away. With livestock pass-on loan projects, they are given an animal and not cash. It is a safer approach and the payback rate is higher.”

There is an importance of community ownership and monitoring as participants cannot avoid deception. This underlines the important role of the project committee.

Breeding management

Initially, you may need to find a source of improved dairy animals outside the country, but within a few years quality animals can be procured from within the country and from project farmers. Purchasing animals locally stimulates quality heifer and goat production and benefits farmers directly who sell animals back to the project for expansion in other areas. A project bull/buck could make a huge impact in the community by breeding with non-project animals, producing not only crossbreds with high potential but also reducing pressure on the project for pass-on offspring. Project bulls/bucks need to be rotated/sold regularly to avoid interbreeding with their offspring.

Integrate/synergize livestock with other initiatives (e.g., agroforestry) and encourage local ownership

Livestock projects do not stand on their own. Farmers integrate livestock into their farming system in mutually supportive ways. Livestock benefit from fodder and by-products of other farming systems, and crops benefit from livestock manure and urine. Livestock also consume plants that are non-digestible by humans. Livestock have many collateral benefits such as biogas for fuel and lighting, and rapid increments of assets to support education, house-building, and other aspirations. As one farmer shared,

“Before we had our cow, our annual income came all at once after the harvest. It was difficult to stretch the money throughout the year. Now because of our cow, we have a regular income. We can obtain simple things like soap, sugar, and tea which had been difficult for our family to afford.”

Encourage farmers to improve their land with investments such as contours with fodder grasses and trees, multi-purpose trees, minimum tillage, and mulching with green manure cover crops.

Figure 2. East Coast Fever vaccination day in Karamoja. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Livestock projects are an impetus for introducing environmentally sound farming practices like agroforestry, zero-grazing, proper soil and water conservation, and adoption of animal-friendly practices like provision of feed and water, regular veterinary services, improved breeding initiatives like artificial insemination, and local vaccination programs. East Coast Fever vaccination (Figure 2) in cattle and Newcastle disease control in chickens are vital to thriving livestock programs. In the case of Newcastle disease control, developing a sustainable vaccination service by farmers themselves is important because services are too cumbersome for the government to provide countrywide.

Consider all stakeholders

Many projects make the mistake of investing all of their assistance in upgrading the people who provide services to farmers. Although improving the effectiveness of government or private extension service is important, investment needs to be balanced among all stakeholders, including farmers. We prioritized investment in farmers over service providers by implementing pass-on loans and related trainings. Both types of investment are needed, but impact is more sustainable if investments reach the end users. A good plumbline of donor priorities is what percentage of the project budget is utilized as direct provision to families the project serves. Budgets speak of priorities.

Livestock development initiatives of NGOs and governments should not be conducted without working together with other stakeholders and service providers in the vicinity. A great program is one in which the farmers do not recognize one service provider over another but understand the vital niche each one plays, be it breeding services, extension staff, NGOs, marketing entities along the value chain, or end consumers. Recognizing the different roles of each actor adds sustainability of efforts and reduces egoism which can diminish the farmer’s sense of self-achievement.1

Encourage local investment, sharing, and caring

A small, streamlined organization with a committed staff is most effective in implementing programs. In the process of seeking an exit strategy, we discovered that there are many ways to disengage through mobilizing local philanthropy and a spirit of sharing and caring among project participants. When participants consider something their own, they are more likely to offer services for free or at low cost. A farmer may be willing, for example, to provide breeding services —by caring for the bull/buck— to help those who would otherwise be unable to afford them. Many farmers will gladly assist a new farmer by building an animal shed, determining contours in their fields, sharing grass plantings or tree seedlings, or sharing knowledge of how to address challenges.

A single “pass-on” offspring is often not enough

Originally, we thought that asking for the first offspring to be given to a neighbor was an excessive demand on a poor family. Quite the contrary, requiring both a pass-on animal to a neighbor, and another pass-back animal over the course of time enabled the local pass-on loan project services to generate income to support their overhead costs.2 Requiring multiple offspring also often kept the family from accumulating livestock too quickly, giving them time to prepare for adequate care of more animals.3

Passing on an offspring to a new family inspired dignity among participants who had never had the privilege of giving something of such value to a neighbor. It inspires hope, excitement, and joy. The pass-on animals were the equivalent of paying back a loan, but it was perceived almost as a sacred act —worthy of celebration— and villagers were given recognition by the community groups for having achieved a successful repayment. This act solidified strong relationships with the new recipient family. Pass-back animals, on the other hand, encouraged families to be given recognition for completing their obligations to the project such as at community pass-on ceremonies. Pass-back animals enabled projects to be more sustainable, generating capital for farmer group development or payment for extension/veterinary services. Contracts can be sustained from offspring if the original contract animal dies, by passing the contract onto the offspring. In the instance of a male offspring, it may be sold to obtain a replacement heifer calf to continue with the contract.

Figure 3. Joyful recipient of a project pig. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Alternative ways should be considered for animal pass-on programs (goats, pigs [Figure 3], rural or village chickens, and layer chickens). There are many traditional ways of sharing, and you might come up with a better method than those suggested above, learned from local cultures. The culture of sharing is not unique to any ethnic or religious group. In the case of fish farming, the sharing or pass-on might be knowledge to new farmers rather than passing on fish fingerlings. In the case of dairy goats prone to twinning, multiple pass-on offspring can be required. With bees, the pass-on may be in the form of funds to purchase a hive. In the case of swine which are prone to multiple births, several pass-on offspring may be justified.

Engage government extension services

Figure 4. Government extension officer treats a zero-grazed project dairy goat. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Often, government extension departments have an interest in supporting farmers but are strapped for funds to pay extension staff or provide them with essential mobility such as motorbikes or bicycles and other working gear. Projects funded by NGOs can consider providing a part of the support of government extension service personnel through incentives such as loans to them to obtain transport (payable by services over a set period of time) and a minimum of operating funds such as fuel, gear to enable them to give livestock vaccines or treatments (Figure 4) and upgrading training opportunities.4 This partnership approach brings benefits to farmers in remote areas who otherwise would never be visited by extension staff. Getting the extension staff out of their offices and into the field improves their morale and sense of self-worth as they build relationships with farmers and bring services, research, and learning nearer to farmers.

Create a local village committee for family selection and preparation for animal distribution

Too often, NGOs do not instill trust in the community leaders among whom they work. Caution is needed, but project success is more likely when led by a local project committees made up of about 10 community members. These committee members should come from a cross-section of society and income levels, ensuring participation from different faith communities, representation of both genders, and a diversity of ages. For details about how to conduct these activities, see the “effective strategies for working with smallholders” section under further reading.

By training project committees in their roles of oversight and agreeing together on criteria of selection of project participants, committees obtain more local knowledge of the character of those chosen to participate. Mistakes of choosing untrustworthy or uncommitted farmers to start a project are often averted.

Beginnings are very important, and the first participants in a project have a big impact on setting precedents and enabling the success of those who follow. Poor preparations before the distribution of livestock on loan leads to higher losses and relaxed standards, all of which ultimately leads to poorer results, lower production, greater death losses, and under-productivity. A strict supervisor and project committee are often not popular at the time of start-up, but the success they bring to a project is ultimately seen.

Figure 5. Joyful member of a local livestock project. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Project committees should never be confined to one faith community, but should cross these lines, thereby instilling a sense of concern for the wider community rather than caring only for those of the faith of the donor or sponsoring church or NGO (Figure 5). This is neither a sustainable nor wise practice. One Muslim farmer named his animal “Unexpected” from his surprise at being considered as a first recipient of a church-sponsored project. It was important to him that no mention had been made of his faith. Another Muslim farmer noted with joy how the project caused villagers of different faiths to meet and purpose together.

Project committees are under great pressure when selecting participant families and receive a lot of requests. Prayerful discernment is needed. A common guideline is that the NGO running the project should not allow its own staff or relatives to be the first to receive livestock. This shows by example that there is hope in waiting for others to benefit first.

Select those capable and needy

It is not easy to identify and assist the poor. However, it is the experience of most of our partner NGOs involved in livestock projects that low-income farmers contributing fully to projects have a better loan pay-back rate than debtors’ repayment to formal lending institutions and governments. Smallholder farmers have high rates of payback both in livestock and their time and effort, serving on project committees, or training other farmers. They are deserving of consideration in livestock projects. Project committees formed with the aid of NGO partners can be more successful in selecting needy but capable candidates for animal loans and administering pass-on credit projects.

Gender should be a priority, and women should be contractually equal beneficiaries of the livestock contracts, training and decisions around use of the use of benefits. It is important to give priority to poor, needy and disadvantaged families, including widows with children, disabled people, and/or families living with HIV/AIDS orphans or those who care for them. It is noble to design projects targeting the marginalized as much as possible, and this is obedient to the call of Jesus Christ. Select projects that are not inherently burdensome to those families.

Select those who will attend training events, follow project guidelines, cooperate with project staff, committees and other farmers, and adhere to written contracts signed by all. Give weight to those who want to improve their standard of living through improved farming and livestock raising and are considered capable of caring for the animals being introduced. Risk is always involved, and failure to select families well can lead to rapid and avoidable losses. Some families who fail due to unforeseen circumstances should be considered again. Those whose livestock perish due to negligence should be required to wait.

Farmers, both men and women, are the best people to train other farmers

Figure 6. Farmer-to-Farmer exchange visit. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Farmer-to-farmer exchange visits are the most cost-effective training known (Figure 6). Volunteer farmer motivators provide excellent extension and training services among other farmers in villages.

Farmer motivators are key to implementing and sustaining successful livestock projects. Volunteer motivators work hard to help their communities by promoting and teaching improved farming systems. They are given the following roles:

(a) training and teaching other farmers

(b) providing extension services and counsel

(c) keeping project records and helping prepare reports

(d) coordinating and monitoring project activities as a link to village project committees

Choose these leaders after the first year of a project. They should be natural leaders by example who have adapted to the project conditions and are keen to help their neighbors. Selection criteria for farmer motivators are important. Projects sometimes choose the motivators too early in the project cycle. It is wise to see if their enthusiasm is sustained beyond the initial euphoria of participation. Farmer motivators need to:

(a) have a desire to help others

(b) be convinced that their efforts are valuable to help reduce poverty and hunger and to improve the health of their neighbors

(c) be team builders i.e., be keen to work with others

(d) have humble spirits, respecting the dignity of others and do not seeing themselves as “experts”

Farmer motivators can be mentored or coached to attain these qualities. The advantages of the farmer motivator are many, such as keeping costs low and enabling a project to cover a larger area without hiring additional staff. Farmer motivators come from within their community, know the people with whom they live, speak the same language, struggle with the same challenges, and understand the culture. They are able to build positive relationships and may not depend upon outside funding. Eventually, they may seek to discontinue, and that is allowable. If their services are needed to continue, they can be paid for their services. An example is being paid for the laying out of contours in fields or assisting in the design and construction of livestock sheds.5

Utilize animal health service providers for training and frontline provision in remote areas

In many countries where veterinary services are lacking —especially in remote areas— governments have undertaken themselves or allowed NGOs to mobilize a front-line cadre of livestock animal health practitioners who are given permission to undertake specific tasks not requiring knowledge at the level of a veterinarian. These activities include deworming, treating common diseases and conditions, simple types of vaccination, and —on an increasing level— more difficult tasks such as minor surgeries (e.g., castration) under the tutelage of district veterinary staff. In many cases, such people are able to undertake tasks that otherwise would remain undone and put livestock in jeopardy or result in high mortality. They can perform the work of first-line notification of contagious diseases.

Choice of these volunteers resembles that of the farmer motivators above. Training is vital for them to be effective, often needing repeat training to consider their limits and emphasize the conditions they are not allowed to perform, so as not to allow them to work in isolation. In some areas, they have been outlawed, partially due to failure to adhere to those limits, and partially due to misunderstandings about the value of their worth and work. When a government is unable to provide animal health workers commensurate with the number of livestock keepers and animals needing services, it is better to enable them to work effectively rather than outlaw them. Sometimes veterinary policies work contrary to their aims of providing good services to remote areas and should be reviewed. This is especially true for the vaccination of rural poultry against the scourge of Newcastle disease.6 Rural chicken flocks are most susceptible to this disease with up to 80% mortality (Amoia et al., 2021).

Livestock distribution can be irrelevant: ‘poultry vaccinations take priority’

Figure 7. Chicken rearing at a household level. Source: Erwin Kinsey

I regret that in my 30 years’ experience with a renown livestock development organization, I did not start early enough to focus on the “livestock of the poor,” that is, rural poultry, as my assumption was that it was easy enough to get, even for the poorest of families. Poultry animals are the lifeline to many farmers’ livelihoods, providing nutrition and income to the lowest economic level (Figure 7). Rural poultry has been shown to be correlated to food security among both farmers and pastoralists especially during drought years as compared to any other livestock species (Savannas Forever, 2006; Wong et al., 2017). It was only after two decades of focus on other species that I realized the profound importance poultry had for low-income families and of the high level at which Newcastle disease was decimating local flocks.

I was late to understand that this is a preventable disease of chickens, and the most viable option created to control it is a one to two eye-drop, thermally stable vaccine which can exist outside a cold-chain for up to two weeks if stored out of sunlight. More important than credit schemes to provide poultry to low-income farmers is the vaccination of their chickens. The low cost per dose and ease and uniformity of its administration —a single drop for a day-old chick as for a mature cockerel — lends to its widespread use. However, most farmers are still ignorant of this life-saving technology. It is an ideal vaccine for women to administer to their own flocks and their neighbors. However, it needs to be done as a pay-for-service to be sustainable.

Many government veterinary regulations prevent farmers from administering this service for payment through trained farmers. At the same time, there is a shortage of government staff who cannot provide full coverage of vaccination services due to the high number of households and high numbers of poultry. Governments and NGOs should do well to work together to ensure that this scourge is controlled by vaccination of all poultry against Newcastle disease three times per year to be effective. Other poultry diseases must also be controlled, but none cause such significant mortality and huge asset losses to the smallholder farmers and pastoralists as Newcastle disease. Poultry vaccination should take priority over introducing chicken rearing though it combines well with such schemes. For more information: http://edn.link/q3yxqg

Cooperate with local partner organizations

Working with local partner organizations, often churches, is more cost-effective and sustainable than an NGO initiating its own projects. The benefits of partnership often outweigh the risks of lack of control.

A consultant once shared,

“I am impressed with the approach of cooperating with project partners. By supporting them to implement the projects, this allows a greater impact in the country than what an NGO could do on its own. It is an appropriate approach, and one which I will recommend to programs in other countries.”

Leadership in those institutions is the key, and servant leadership is the model. Good leaders balance assertiveness and personal skill with respect for local knowledge and culture. They listen, admit when they are wrong and are open to change. A culture of transparency, democracy, inclusion, and accountability is a prerequisite for any successful farmer group, so corruption does not occur among individual leaders.

Some project sponsor leaders misused their influence to obtain assistance and misdirected it. However, for the most part, I felt honored and proud of the way many selfless leaders of the project sponsoring organizations put others first and ensured that the projects helped the needy

Pass on the gifts

Figure 8. Example of a zero-graze structure for containing animals. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Participants in projects can increase in number through

(a) A unique system in that each participant, in turn, pays back to the project multiple offspring, some of which go to new farmers, and the sale of some goes to support the extension back-up supervision. In this way, the number of contract farmers does not remain the same but increases as each farmer assists by providing offspring on a contract basis.

(b) Promotion and use of project breeding males on other village members’ livestock if they do not exceed the strength of the male and adherence to good disease prevention is adhered to. Eventually the entire village can potentially have “improved” livestock genetics through crossbreeding.

(c) Rotating or replacing male breeding stock regularly, such as every year for short-term breeding (goats, sheep, swine, chickens) and longer periods for cattle, camels, and donkeys.

(d) Education: Participants should pass on training to their neighbors, particularly that which emphasizes the physical preparations required prior to receiving animals. These include fodder tree and grass planting on contours and animal-friendly grazing livestock sheds which allow the livestock to have exercise, feed and water at all times, as well as a dry and clean place to rest (Figure 8).

Stay focused on helping families in need

Don’t lose project focus; it should remain on low-income families. Participating families chosen by village committees on the basis of need and ability are likely to experience profound impact. Adding another dairy animal to someone’s already established herd will make minimal impact. Impact studies have shown that small livestock like dairy goats can double the income of a low resource family and significantly enhance child nutrition. Despite targeting the poorer sector, survival rates are acceptable overall, although losses are higher in coastal areas than elsewhere, and when severe climate events occur such as El Niño.

Figure 9. Women member of a community-level livestock project. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Aim for improving the wellbeing of whole families through equal gender consideration. Empower women to make decisions, providing them with the opportunity to be cosigners of contracts as livestock recipients. At least an equal number of women should serve on village selection committees. In-village training better caters to the needs of women than residential training, which is more expensive and harder to attend. This will give women equal shares in project benefits (Figure 9).

Select the appropriate livestock for the family/community

- Use of local and ‘improved’ exotic crossbred animals is a surer way to start up a project, as there is increased survivability, lower demands for nutrition, resistance to some diseases, and a better chance of survivability and therefore, learning by doing. Farmers often prefer pure exotics and suffer losses because of their vulnerability. It is better that they work toward pure exotics if they can prove their own ability to manage livestock.

- Exotic animals may have high genetic potential, which farmers readily recognize; however, success with such animals often requires improved standards of husbandry.

- Less successful farmers do better with lower demanding livestock, such as rural chickens, meat rather than dairy goats, goats instead of crossbred cattle, or crossbreds rather than pure exotics.

- If the candidate already has some livestock, consider their current herd/flock size and the available supply of food, water, and shelter for animals to ensure that there are enough resources to meet additional livestock demands.

- Train the right person! “In Africa we generally have farmers and their husbands.” Ensure you train the people nearest to the livestock! Too often, most training funding is utilized on the owners (men) and not on the people caring for the animals (women).

Make the project sustainable

By working with local partners

Mobilizing local NGOs, in particular, churches, women’s groups, and primary societies to act as trustees of the project, is more effective than working through district governments or external NGOs who experience short project cycles and then leave. Local NGOs effectively choose target communities, design and revise project loan criteria, ensure adherence to project guidelines, provide back up support and allowances to project supervisors, deal with conflicts or problems in the villages, and collect contributions from farmers to run the project monitoring and follow-up. In the absence of autonomous, bonafide farmer cooperatives or associations, these trustees are indispensable to the sustainability of livestock projects. Alternatively, where projects do not take an active role in developing and adhering to criteria of selection and preparation, where leadership within the trustee organization may have competing agendas, or where they take advantage of their position to target project assistance to their own leaders, their participation can be a hindrance rather than a help.

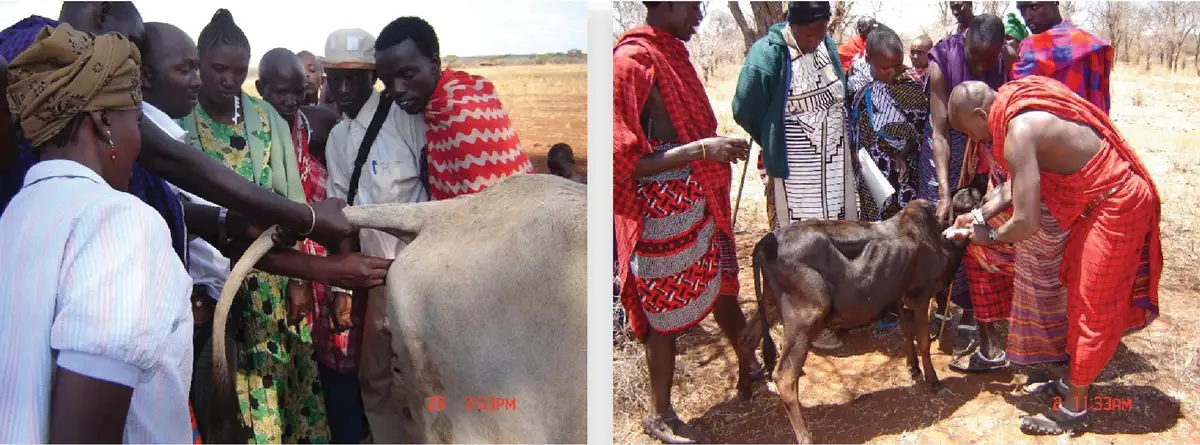

By building self-reliance of local farm extensionists and community animal health workers

Empowerment of farmer motivators and community animal health workers in remote villages reduces dependency of projects on government extension staff and continued donor support. These farmer volunteers are chosen by the original farmer recipients or the village project committees, to attend a two- to four-week training (Figure 10) and then to provide assistance by example as well as by technical or veterinary support, as needed. Project supervisors share that these volunteers enhance the adoption by a larger village population, the innovations promoted by the project and have reduced the number of cases of project animal diseases that reach the supervisors.

Figure 10. Trainings of community animal health workers. Source: Dr. Honest Ndanu

By establishing local credit committees

Figure 11. Project committee meeting. Source: Erwin Kinsey

A project can help localize the authority and ownership of the projects by forming committees at the village or subvillage level to recommend farmers for selection, enforce bylaws of the group, hold regular meetings (Figure 11) and conduct in-village training. Some of these committees, from the author’s experience, have been more active than others to manage group funds and to engage in other activities decided on by the group such as running a village inputs store or marketing milk. These committees need to be regularly reformed and eventually should be made up largely of participant farmers continuing to move toward self-reliance. These may become the grassroots associations that make up the future dairy farmers’ cooperatives in each area. It is evident that forming these associations must be voluntary to be effective and that initiatives to provide assistance to strengthen these associations need to be demand-driven and catered to particular needs of each group to produce lasting cohesion. Most dairy goat groups still need support in technical extension, group leadership, and accountability. The earlier they can undertake economic ventures, with guidance in business planning and how to obtain formal credit, the sooner sustainability is achieved and with greater economic impact.

By implementing a well-planned exit strategy

“Livestock projects” eventually need to discontinue, and donors need to seek strategies which allow them to exit after a certain level of support for a given time. Credit project partners should still work with low resource farmers by inputs of livestock, extension services, and training/mobilization in environmentally sound farming practices until livestock groups can continue on a self-sustaining basis. This applies to cooperatives, associations, and intermediary service providers. As projects come to an end, diminish the dependency of farmers on subsidized services. Plans to do so should be part of a good exit strategy planned from the start of the project. Gradual lowering of the number of farmers relying on subsidized services can be accomplished by providing services at-cost and to “graduate” farmers from the projects through formal or informal ways.

Conclusion

Poverty reduction must remain a primary objective of livestock development programs. Challenges such as diminishing access to land and water resources and limited extension and veterinary services remain in East Africa. Yet, as mentioned at the outset, livestock on the farmstead provides smallholder farmers with income streams they would not have by growing crops alone. Lessons learned from the author’s years of experience working with livestock projects in Tanzania provide insights into principles and practices for improving lives of the marginalized with livestock interventions. These key lessons are summarized in the following table:

| Potentially Beneficial Practices | Potentially Detrimental Practices |

|---|---|

| Use cross-bred livestock |

Start with exotic breeds |

| Use an “pass-on” contract system at the family level | Create a breeding farm |

| Prepare, start slow | Start quickly with little preparation |

| Create and empower a local committee for participant selection | Give livestock to everyone requesting them |

| Feel comfortable starting with low-income families, trusting them to pay back loans | Distrust families based on their current income |

| Match livestock type to community capacity | Select livestock based only on your thoughts |

| Select and train/retrain farmer motivators from the community on important topics | Create dependency on your project for training and resources |

| Bring in government extension workers in creative ways | Assist those who already have many livestock, have set husbandry patterns, or are not open to change |

| Celebrate “pass-back” animals to help sustain project services | Give priority to family, friends, or those who live outside of where the project committee can supervise |

| Introduce sustainable farming practices alongside animal projects |

Give priority to those who do not own the land they use |

| Promote husbandry changes (e.g. zero-grazing) | |

| Be inclusive (religion, age, gender, income level) |

Limit participants to your faith or group preference |

| Encourage local ownership and responsibilities |

Consider the practices in the Table when starting livestock projects. Apply the material wisely, according to your local context.

References

Amoia C.F.A.N., P.A. Nnadi, C. Ezema, and E. Couacy-Hymann. 2021. Epidemiology of Newcastle disease in Africa with emphasis on Côte d’Ivoire: A review. Vet World, 14(7):1727-1740. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2021.1727-1740.

Savannas Forever. 2006 Impact Evaluation Report of Global Service Corps Outreach. University of Michigan.

Wong, J.T., J. de Bruyn, B. Bagnol, H. Grieve, M. Li, R. Pym, and R.G. Alders. 2017. Small-scale poultry and food security in resource-poor settings: A review. Global Food Security, 15:43-52.

Further Reading

Livestock management and production

Agrodoks - http://edn.link/agrodok

Christian Veterinary Mission (CVM) Publications - http://edn.link/cvmpub

CTA Publications - http://edn.link/ctapubs

FAO Publications - http://edn.link/faopubs

Force, Bill, 1999. Where There Is No Vet. London: Macmillan Press.

Hatcher, Gordon. 1984. A Planning Guide for Small-Scale Livestock Projects. Little Rock, AR: Heifer Project International

Heifer International - Selected Publications - http://edn.link/heiferpubs

Jacobs, Linda. 1986. Environmentally Sound Small-Scale Livestock Projects: Guidelines For Planning. Arlington, VA: VITA Publishing Services

Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards Publications and Resources - http://edn.link/q4ee4e

Mikkelson, K.O. 2019. Animal Integration and Feeding Strategies for the Tropical Smallholder Farm: Approaches and Methods for Increasing Sustainability and Profitability. ECHO Asia Impact Center.

Mkulima Mbunifu (MkM) - http://edn.link/mkm

Morrison, F.B. and William Amon Henry, 1948. Feeds and Feeding: A Handbook for the Student and Stockman, 21st edition. Chicago. Lakeside Press

World Organization for Animal Health Resources - http://edn.link/d77y9k

Effective strategies for working with smallholders

Aaker, Jerry, 1993, Partners with the Poor: An emerging approach to relief and development. New York: Friendship Press.

Aaker, Jerry, and Jennifer Shumaker. 1994. Looking Back and Looking Forward: A Participatory Approach to Evaluation. Little Rock, AR: Heifer Project International

Batchelor, Peter. 1984. People in Rural Development. Exeter, U.K.: The Paternoster Press.

Bunch, Roland. 1982. Two Ears of Corn. Oklahoma City: World Neighbors.

Chambers, Robert. 1983. Rural Development: Putting the Last First. Routledge Publishers.

Flanagan, B. 2015. Modernizing Extension and Advisory Services Summaries http://edn.link/meas-summaries

DeVries, James 1992. “Development or Transformation; Reflection on a Holistic Approach to People Centered Change.” Little Rock, AR: Heifer International

Global Service Corps Tanzania. Rural Empowerment Project plan. - http://edn.link/7rqzyk

Hope, Anne, and Sally Timmel. 1984. Training for Transformation: A Handbook for Community Workers. Zimbabwe: Mambo Press.

Rientjies, Coen, Bertus Haverkot, Ann Waters-Bayer 1992. Farming for the Future: An Introduction to Low-External Input and Sustainable Agriculture. London: Macmillan Press.

Schumacher, E.F. 1973, Small is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered. New York: Harper and Row.

Annex 1: A historical perspective on livestock development in Tanzania

Twenty-three years ago, the Worldwatch Institute’s annual report, Vital Signs 2001, painted a picture of trends over the past fifty years ( now 75 years). These included a significant increase in world poverty and declining living standards of the world’s poor. Little has changed since then. Micro-credit for those not served by commercial banks and other lenders was mentioned as a sign of hope. This phenomenon expanded rapidly in the past two decades and offered particular hope to women who have accounted for a large proportion of the small loans. Another hope was ethical consumer initiatives such as support for organically grown and fair-trade produce, giving added value to smallholder farmers. These initiatives have provided a lifeline and entry-point for new smallholder farmers to enter farming.

The globalization of industry and trade created a spreading threat to the diversity of crops, ecosystems, cultures, and the livelihoods of the world’s smallholder farmers who have often proven to be the most knowledgeable stewards of the land. In all parts of the world, smallholder farmers have been battered in the past 75 years. While few conglomerates have dominated every link in the global food chain, farmers are under dramatic decline, and their share of income from food has continually decreased throughout this period. Structural adjustment requirements, trade liberalization, and the growing emphasis on agricultural grades and standards deepened the crisis for smallholder farmers. Many farmers have tended to hold on long after it was clear that they could not compete, at least for the sake of food and employment security through subsistence farming. Prospects for them to gain political strength on their own have only continued to shrink.

The best alternative remaining for smallholder farmers is to develop their local food economies, shorten the distance between producers and consumers, and ensure that local economic activities benefit the local community. The government has a role in establishing an enabling environment for local smallholder production, including establishing infrastructures and favorable policies while also protecting the subsistence economy. Micro-credit or microfinance must assist the primary producer as well as increase enterprises that promote value-added products.

Figure 12. Cheese makers selling their goods at the Morogoro National Agriculture show. Source: Erwin Kinsey

Several actors were originally involved in support of peasant farmer dairy production in East Africa through micro-credit and training (heifer-in-trusts). During a twenty-year period from 1980 to 2000, the impact was significant. Exotic dairy cattle and their crosses more than doubled in the hands of smallholder urban and rural farmers, primarily as a result of the dairy credit schemes emulated by many actors. These projects developed first in the highlands and coastal zones of East Africa and now produce more than 20% of the domestic milk supply, replacing what was produced before by the settler economy. Smallholders produce an estimated 95% of the marketed milk in Tanzania. This has increased milk production in rural areas, and availed milk and milk products for sale in urban centers (Figure 11). The nutritional improvement and higher income levels have enabled a large number of these families to avoid dire poverty. Thousands more have indirectly benefited through access to improved livestock, training, and availability of milk and meat. Agricultural extension services to these families have been enhanced, creating measurable indirect and direct impacts. The growth of dairy marketing hubs has been a rather recent phenomenon, providing microcredit to families who would otherwise not qualify for bank loans.

Dairy production in Tanzania is and will likely remain predominately by smallholder dairy farmers and traditional pastoralists. Beneficial effects of initiating smallholder dairying in rural towns and villages include:

- improved income generation

- rural employment

- nutritional improvements

- school attendance

- stemming urban migration

- improving the environment

- increasing agricultural production

The sustainability of the dairy industry depends on looking at the wider picture as well. The real price for milk has declined in Tanzania to the point that many farmers no longer maximize production of their animals because of the lack of good milk markets. The milk processing industry, which for twenty years was dominated by government entities, was never able to engage successfully the majority of milk producers to channel their milk through formal channels. With the demise of the government control, some transformation has taken place where small dairy collection and processing units dominated by the private sector and marketing agents have proliferated in many small towns.

Entry points for new investors in the sector may be to focus on small entrepreneurs or village groups to access credit, for the following potential enterprises connected to livestock value chains:

- milk collection centers

- mini-dairy processing centers

- milk peddlers/coolers & bicycles

- commercializing the work of community animal health workers (services for pay)

- commercializing the work of farmer motivators (services for pay) and soil conservation/agroforestry trainers

- artificial insemination mobilization on a private basis (services for pay)

- beehives promotion/credit

- honey/beeswax extraction and marketing

- mobilizing technicians to provide services for biogas construction (services for pay)

- tree nursery mobilization and marketing training

- mobilizing technicians to provide services of facilitation of village natural resource management plans, as a micro-enterprise where the client may be the village, the district or private donors

- retail shops for locally produced farm-processed products

- linking organic farming producers and consumers within and outside the region and other micro-enterprises as demands arise.

Annex 2: Further ways to maximize the success and self-reliance of local credit committees

For the continuation of credit and related services, local organizations need to see the “projects” as their own and not the donor’s. A self-assessment approach needs to be taken with projects, even those which have been too top-down from the start. Local organizations need to set their own directions with guidance, and to assess their training needs in order to assume full responsibility. Where there is no willingness to continue the credit and extension services by the group, a strategy for collection and redistribution of pass-on offspring to well-organized areas may encourage the group to sustain their pass-on loan program or to move it elsewhere.

Increase voluntary involvement by the credit committee members in the farmer preparation and monitoring, through mobilization and delegation of work to farmer motivators who can give time to assisting their neighbors or assigning a small number of farmers under preparation to each committee member. Simple recognition is often enough motivation for these volunteers to give valuable time to their communities. Other motivations can be institutionalized, such as remuneration for services rendered if funding is available for it.

Increase capacities of:

- members of the credit committees at the village level so that they are able to keep minutes/records/accounts, work in a democratic way, and are able to do wealth-ranking effectively to select the appropriate farmer participants.

- staff of the local institutions coordinating the credit and extension services (if they exist; otherwise, this training should be provided to members of the credit committees who contract to assume these tasks in the absence of another overseer organization), that they are encouraged to plan, budget, generate funds from local (for operations) and external (for expansion) sources.

- farmer volunteers (motivators and community animal health assistants) who have shown themselves to be very effective at providing extension and veterinary services where they are lacking from the private, commercial, or government sectors.

- livestock extensionists, whether private or public, active in these areas, that they remain committed to continue to provide extension support with or without remuneration from the groups.

All of the above capacity building can be cost-shared with the participants, especially if the training needs are identified by the participants so that there is genuine motivation to increase their capacity.

The local organizations (project holders/trustees ) generate funds and contributions by volunteerism from farmers within the area. This can be done by:

- contracts written with consent of the farmers to require multiple offspring, including one for sale to generate funds for extension/expenses involved in follow up of the credit,

- provision of a revolving fund for veterinary drug/animal inputs under the supervision of the supervisor and/or village groups/and/or project holder organization, and monitoring its growth over a period of time that a habit of accountability is established,

- receiving monetary contributions from farmers on a regular basis, possibly to set up credit societies if the fund grows accordingly, such as to become a village savings and loan group based upon investments from members,

- monetarizing animal loans so that farmers have the option to repay pass-on loans with money generated from their animals rather than waiting for an elusive payback animal. As more farmers benefit, more potential is generated for local contributions toward supervision and expansion.

- mobilizing and training farmer motivators and community animal health workers (farmers) in projects where they presently do not exist.

Cite as:

Kinsey, E. 2024. Livestock Projects. ECHO Best Practices Note no. 9.