- Two Series on Veterinary Care: Raising Healthy [Animals] Under Primitive Conditions and Ethnoveterinary Medicine in Asia

- Book Review: Natural Veterinary Medicine

- Poultry in Tick Control on Cattle

- Tick Control Potential

- Homemade Dewormer for Goats

- Veterinary Students at Michigan State University are Available to Answer Questions

- Course in Tropical Animal Health and Production (in French)

TWO SERIES ON VETERINARY CARE. Raising Healthy [Animals] Under Primitive Conditions. These booklets provide a lot of information! Each booklet (80-180 pages) summarizes basic care of an animal, with housing and equipment, flock/herd management and nutrition, and disease and parasite prevention and control. The books are like summaries of a textbook on each animal. Nutrient components of various tropical feeds is particularly interesting. Medicines and dosages for common illnesses are also listed, for those with access to commercial treatments.

The booklets are written by veterinarians with Christian Veterinary Mission. Titles in the series include Pigs, Rabbits, Fish, Goats, Beef Cattle, Poultry (also in Spanish: Aves de Corral), and Dairy Cattle. Booklets are US$5 each in developing countries, $7.50 elsewhere. Books on Horses, Sheep, and Drugs and Their Usage are expected in 1996. Look for: Slaughter and Preservation of Meat, Where There Is No Vet (in the style of WTINDoctor), and some translations of these books into Spanish and French in 1997. Write Dr. Leroy Dorminy, the founder of Christian Veterinary Mission, 19303 Fremont Ave N, Seattle, WA 98133, USA; phone 206/546-7343; e-mail ald@CRISTA.wa.com.

Ethnoveterinary Medicine in Asia: an information kit on traditional health care practices is another excellent publication by IIRR. This 4-part kit (400 pp.) outlines remedies using locally available plants and simple techniques. Traditional practices throughout Asia were collected and discussed among workshop delegates from seven Asian countries.

The booklets are in IIRR's very hands-on, well-illustrated style. The first book includes the preparation of medicinal plants, simple surgeries, and a list of all the ethnoveterinary plants (about 250) listed in the series. Many of the plants are weeds or food plants common in the tropics; some are specific to Asia. The other three books are on ruminants, swine, and poultry. Diseases are discussed according to symptoms, causes, prevention, and treatment. Practical dosages and complete instructions for preparing and administering the herbal medicines are given in every case.

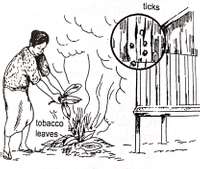

A few examples from each book should give you an idea of the material. For  ruminants: treat constipation with a salted banana blossom; 10 plants used for internal parasites; safe management of infectious diseases; and simple housing models. For swine: treat piglet anemia with Moringa leaf extract; use Leucaena seeds to treat for roundworm; and various rinses for eye infections. For poultry: smoking bird houses for ticks, lice, and mites (see picture from the book); and how to care for infected wounds using oil and ash. To order: in the US, send a check for US$17.25 payable to IIRR; overseas, pay only by int'l money order, US$18 for overseas surface mail at IIRR, 475 Riverside Dr., Room 1035, New York, NY 10115, USA; phone 212/870-2992/fax -2981; e-mail iirr@cce.cornell.edu. In Asia, contact IIRR Bookstore, Silang, Cavite 4118, PHILIPPINES; phone (63-9-69)-9451/fax -9937; e-mail iirr@phil.gn.apc.org. Pay US$11.40 in the Philippines, $18 airmail within Asia.

ruminants: treat constipation with a salted banana blossom; 10 plants used for internal parasites; safe management of infectious diseases; and simple housing models. For swine: treat piglet anemia with Moringa leaf extract; use Leucaena seeds to treat for roundworm; and various rinses for eye infections. For poultry: smoking bird houses for ticks, lice, and mites (see picture from the book); and how to care for infected wounds using oil and ash. To order: in the US, send a check for US$17.25 payable to IIRR; overseas, pay only by int'l money order, US$18 for overseas surface mail at IIRR, 475 Riverside Dr., Room 1035, New York, NY 10115, USA; phone 212/870-2992/fax -2981; e-mail iirr@cce.cornell.edu. In Asia, contact IIRR Bookstore, Silang, Cavite 4118, PHILIPPINES; phone (63-9-69)-9451/fax -9937; e-mail iirr@phil.gn.apc.org. Pay US$11.40 in the Philippines, $18 airmail within Asia.

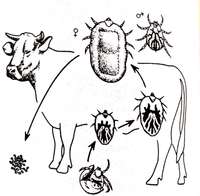

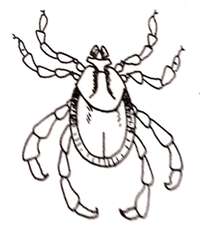

NATURAL VETERINARY MEDICINE by Uly Matzigkeit. The Swiss agricultural information network, AGRECOL, has published a 183-page book on ectoparasites of animals in the tropics (i.e. in contrast to internal parasites). They see this as a sequel to their exceptionally useful book Natural Crop Protection in the Tropics by Gaby Stoll. Consequently, 80 pages are devoted to "Insecticidal, repellent and wound healing plants." The botany and propagation of the plant is summarized (often a botanical drawing is pictured to help in identification), then uses are briefly discussed and references listed. Sometimes I find this crucial how-to section frustratingly brief with many unanswered questions, but this is probably due to the inadequacies in the literature upon which they had to rely. A research scientist could find a wealth of research ideas by looking for these gaps. The first 86 pages discuss the ectoparasites  of primary importance. Each section includes a picture of the parasite (see picture from the book), a discussion of its life cycle, hosts, symptoms/damage and control measures. Some "gems" from the general discussion follow.

of primary importance. Each section includes a picture of the parasite (see picture from the book), a discussion of its life cycle, hosts, symptoms/damage and control measures. Some "gems" from the general discussion follow.

"Plant preparations applied for ticks should be applied especially when resistance to ticks is low. Some factors having influence on tick resistance are: (1) Livestock shows its lowest resistance in tropical autumn. (2) Female calves are more resistant to ticks than males. (3) Young cows are more resistant than old ones and sucking calves more than their mothers. (4) Pregnancy might lower resistance, especially in the last stage. (5) Lactation also lowers resistance, especially at the end of lactation.

"It is of great importance to assure a confrontation of cattle with ticks and tick vector diseases in areas where anaplasmosis and babesiosis is prevalent (not more than 10 engorged female ticks/animal!). Animals kept tick-free for long periods will lose their immunity to these diseases and a heavy reinfection might be fatal. Newborn animals should not be kept tick free for the first half year, when they can gain a natural immunity."

The book can be ordered in English or French for about US$25 plus postage from Margraf Verlag, P.O. Box 105, 97985 Weikersheim, GERMANY; fax 49-(0)7934-8156. The book is also available for 28.50 SFr (about US$23) plus postage from AGRECOL, c/o Oekozentrum, CH-4438, Langenbruck, SWITZERLAND. By the way, we asked if an endoparasite book is planned, but it is not.

POULTRY IN TICK CONTROL ON CATTLE. Nicola Mears wrote, "Here in coastal Ecuador the area has been transformed in the last 20 years from tropical forest to cattle farms, so the ecology has changed dramatically. Perhaps this is why we have a population of ticks that is absolutely out of proportion. Controlling them has become worse over the past 5 years. All animals must be sprayed with insecticide at least weekly. Until a correct dose was established many cattle and horses were lost (and who knows how many children were affected). I am continually asked if there is a biological control for ticks."

The International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology in Nairobi says that poultry might be able to play an important role in reducing tick populations. A brief excerpt from Spore magazine quotes their studies as showing that engorged ticks generally drop from their hosts either late in the evening or early in the morning. This leads them to suggest that, if cattle are kept in their kraals [enclosures] at those times, and chickens are allowed access to the kraals, the chickens would pick up the engorged ticks.

Marsha Hanzi with the Instituto de Permacultura da Bahia in Brazil wrote, "Regarding ticks on cattle, this is also a serious problem in the Brazilian altiplano, where it has been successfully kept within limits with the guinea fowl. They have the advantage over the chicken of liking the hot climate and of adapting to the wild. They virtually become wildlife, living and reproducing without human aid.

"Proliferation of ticks is a sign of soil degradation, at least here in Brazil. On our farm we had an outbreak only when the pasture became old, even though the neighbors farms were always infested. Healthy animals on healthy soil have relatively few ticks. I personally suspect it has to do with microelements which are often deficient in tropical soils. One homeopathic doctor suggested that adding a little sulfur to the cattle's drinking water helps increase resistance. It seemed to work in our case."

These comments were from L. E. Andrews in Houston, Texas: "I think the solution is with guinea fowl rather than chickens. They love to eat ticks, as well as beetles, spiders, flies, etc. A big plus is that they eat snakes. We have a lot of copperheads in this area. A friend bought some land that was infested with copperheads and some rattlesnakes. In 3-4 years after bringing in some guinea fowl you could not find a snake on the property. They eat the small snakes and gang up on larger ones, pecking them to death. They also eat young mice. They are the best watch dog you can have to alert you of any activity at night.

"I'd recommend raising the young (called keets) in a pen near the feed lot to help them bond to the cattle. Feed them just a little grain and a lot of ticks (you could hire kids to collect the ticks). When they are mature, they will form teams moving through the fields and feed lot. Feed them only a little bit, at night, in the feedlot with the cattle to encourage them to center around that area."

[Ed.: Thanks for the good suggestions. Beware, though, if you have a lot of mulched gardens. Several years ago ECHO obtained 12 guinea fowl because I read that they would go through gardens eating only insects and leaving plants alone. A week after we turned them loose on the farm we butchered them all. They did not eat the plants, but they were a disaster in our heavily mulched gardens. Their constant scratching quickly dug out some plants and buried others. If we did not use so much mulch they would have become a permanent fixture here.]

David Showalter in Paraguay said, "Concerning ticks, one farmer keeps chickens in a  grove of trees, where they run loose. When the cattle come into the woods in the heat of the day, the chickens eat the ticks right off of the cattle. The cattle get used to this and do not seem to mind."

grove of trees, where they run loose. When the cattle come into the woods in the heat of the day, the chickens eat the ticks right off of the cattle. The cattle get used to this and do not seem to mind."

From Daniel Priest in Bolivia: "I just received the latest EDN and noticed that people continue mentioning chickens for tick control in cattle. Since I have had a little experience with this, I thought I would write.

"First, good `indicus' (hump on the back) cattle are naturally very resistant. Crossing with European breeds usually gives potential for higher production, but also greatly increases the tick problem. There is a wide variation in degree of tick resistance in those cross-bred cattle, so selection can be very effective.

"Several years ago I bought Brown Swiss bulls to cross with Nelore. The bulls, and their progeny, had a very high capacity for picking up ticks. The cattle would come to loaf in the yard where we also raised chickens. The chickens would pick the cattle clean, even jumping a couple of feet in the air to grab a juicer, and the cattle seemed to enjoy it. A side advantage was the nutrition of the chickens.

"After about three years I started to notice indications of a significant transfer of fertility from the pasture to the loafing area. Because of this I stopped letting the cattle spend much time in the same area. Now, although the cattle do spend a little time near the chickens, both cattle and chickens seem to have lost the custom. Apparently the two must spend a good bit of time together to get acquainted and start to help each other out.

"A practice that is becoming more widely used in Brazil is the feeding of the aerial part of the cassava plant to cattle. It must be chopped and left for a day before feeding to lower the toxicity. Not only does it contain around 12% crude protein, but it controls ticks, probably due to the small amount of prussic acid remaining even after drying for a day. Although this practice is encouraged by Brazilian researchers, I still wonder if it might not adversely affect the beneficial micro-organisms in the rumen as well as the ticks." [Does anyone have more information concerning this? Perhaps an extension bulletin from Brazil?]

TICK CONTROL POTENTIAL. According to a USDA press release, young ticks died and adult ticks shied away when they touched extracts from an African plant, Commiphora erythraea (Haddi tree). A syrupy oil bearing the chemicals was made from the thick gum of the plant. "In Africa, the oil is rubbed on cattle to repel ticks and insects and soothe cuts, bruises and scabies. It is also used as a perfume because of its pleasant odor. The plant is closely related to myrrh, known for its Biblical reference as a gift of one of the wise men." We have been unsuccessful in obtaining seed for this plant, or even to learn any of its common names. Can anyone in Africa help with information or seeds?

HOMEMADE DEWORMER FOR GOATS. According to the September 1991 Sustainable Agriculture Newsletter, some small farmers in the Philippines are using ipil ipil (Leucaena leucocephala) seeds to deworm young goats. About 50-100 young seeds are removed from the pods and are pounded to form a paste. This is mixed with 5-8 ounces of water and given to the goats as an oral drench. The laxative effect kills or expels the ascaris (Ascaris lumbricoides?) and other stomach worms.

VETERINARY STUDENTS AT MICHIGAN STATE UNIVERSITY ARE AVAILABLE TO ANSWER QUESTIONS. Since 1986, students in the veterinary department at MSU who have an interest in Third World development have been organized to help missionaries and others doing similar work when animal health problems perplex them. They get an average of 10-20 requests per year. There are two main ways in which they have helped people to date. (1) People have written with disease symptoms and they have tried to diagnose the likely problem. A few times someone from MSU or known to them has been traveling in the area and was able to actually visit to assist with especially difficult problems. (2) They have sent literature that they believe will answer a problem, or particular articles that someone has requested.

Contact the faculty director Dr. Edward C. Mather, Coordinator of International Programs, G-100 Veterinary Medical Center, College of Veterinary Medicine, Michigan  State University, East Lansing, MI 48824-1314, USA; phone 517/432-2388; fax 517/432-1037.

State University, East Lansing, MI 48824-1314, USA; phone 517/432-2388; fax 517/432-1037.

COURSE IN TROPICAL ANIMAL HEALTH AND PRODUCTION (IN FRENCH). After receiving his masters in horticulture from Florida, Pete Ekstrand went to the Prince Leopold Institute of Tropical Medicine in Antwerp, Belgium for a year of study before beginning work in Zaire. I could tell from his exciting letters that he was gaining much from the studies, so I asked him to write a bit about the school. "The course lasts for ten months (early October through June). It consists of two programs, one in animal health and hygiene and the other in animal production. In the first program we studied tick-borne diseases, trypanosomiasis, other protozoan diseases, insect control, infectious disease and the role of veterinarians in prophylactic campaigns. In the second we studied agronomy, fodder crops and natural pastures, animal husbandry, management of farms and stations, construction, molasses and non-protein nitrogen, agricultural by-products, trade policies, wildlife use, hydrobiology, fish farming, handling of hides and skins, biometry and statistics.

"So what do I think of it? I have thoroughly enjoyed the course! Although French is a second language and I was able to study it only four months, I have had no problem following and understanding the material, except for the expected new vocabulary. In fact, they greatly helped my French. The students this year are from Bolivia, Spain, Zaire, Benin, Ghana, Cameroon, Ivory Coast, Togo, Belgium and the USA (myself). It has been enjoyable and enlightening to talk with them about situations and potentials in their countries. The professors have had experience in developing countries and are current in what they teach. I have been impressed with their knowledge and understanding of all the parameters involved in development. I am sure the year will greatly benefit my future work in Zaire."

The only fee mentioned in the catalog is 42,000 BF registration, about US$1400. For more information, write to Institut de M‚decine Tropicale Prince L‚opold; D‚partement de Production et Sant‚ Animales Tropicales; Nationalestraat 155, B-2000 Antwerpen, BELGIQUE; phone 32/3/2476666; fax 32/3/2161431.