“Value chain” has recently emerged as a popular business and development concept. The growing integration of the global economy has provided the opportunity for substantial economic and income growth. Improving value chains, which include Small Holder Farmers (SHF) is recognised as having potential to reduce poverty. Inclusiveness, an essential ingredient of any successful growth strategy, is a concept that encompasses equity, equality of opportunity, and protection in market and employment transitions. Inclusive value chains are economically profitable, environmentally and socially responsible, and integrate low-income communities or producers.

“Value chain” has recently emerged as a popular business and development concept. The growing integration of the global economy has provided the opportunity for substantial economic and income growth. Improving value chains, which include Small Holder Farmers (SHF) is recognised as having potential to reduce poverty. Inclusiveness, an essential ingredient of any successful growth strategy, is a concept that encompasses equity, equality of opportunity, and protection in market and employment transitions. Inclusive value chains are economically profitable, environmentally and socially responsible, and integrate low-income communities or producers.

A value chain is defined as a full range of activities, which are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the different phases of production, delivery to final consumers, and final disposal after use (Kaplinsky et al. 2000). A value chain is a strategic alliance, an economic system by which chain actors jointly and harmoniously function for mutual benefits. Value chains vary in length and number of actors. Most chains start from supply of inputs and extend to the final marketing of products. Product(s) and the end markets are most often used to identify a value chain, e.g. packed wheat flour for export market, poultry meat for local market etc. For a successful market linkage or any value chain based intervention, a value chain analysis is a prerequisite. A value chain analysis focuses on generating an understanding of the dynamics of the value chain, which include, but are not limited to: identification of actors (i.e. both primary and secondary) and mapping the value chain, analysis of economic and profitability along the chain, identification of the end markets, identification of the business enabling environment and value chain governance structures.

Sample cases of value chain mapping and analysis

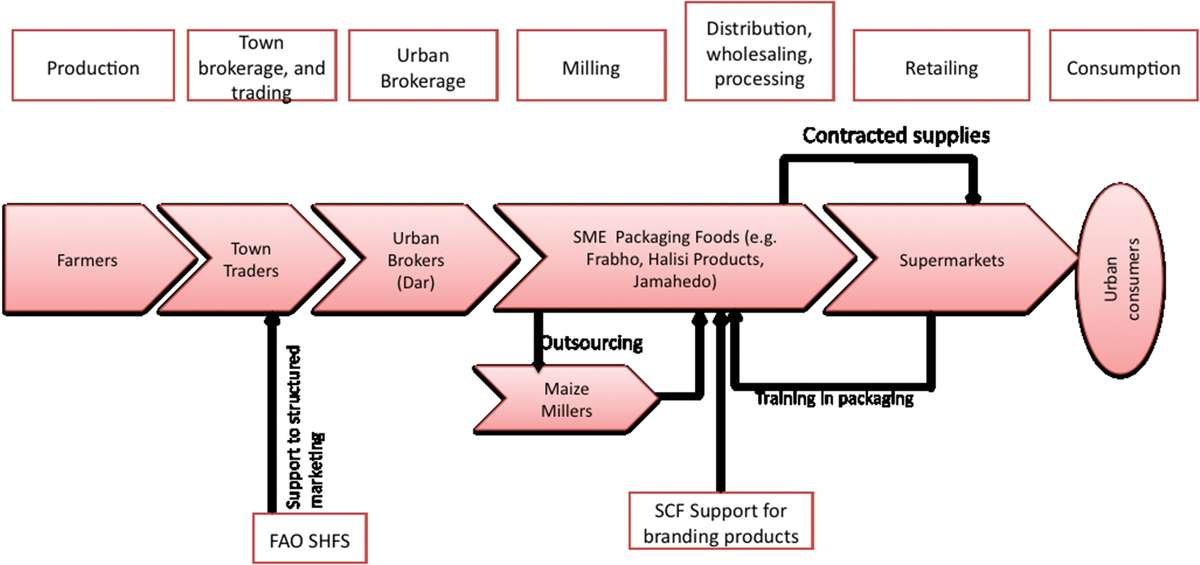

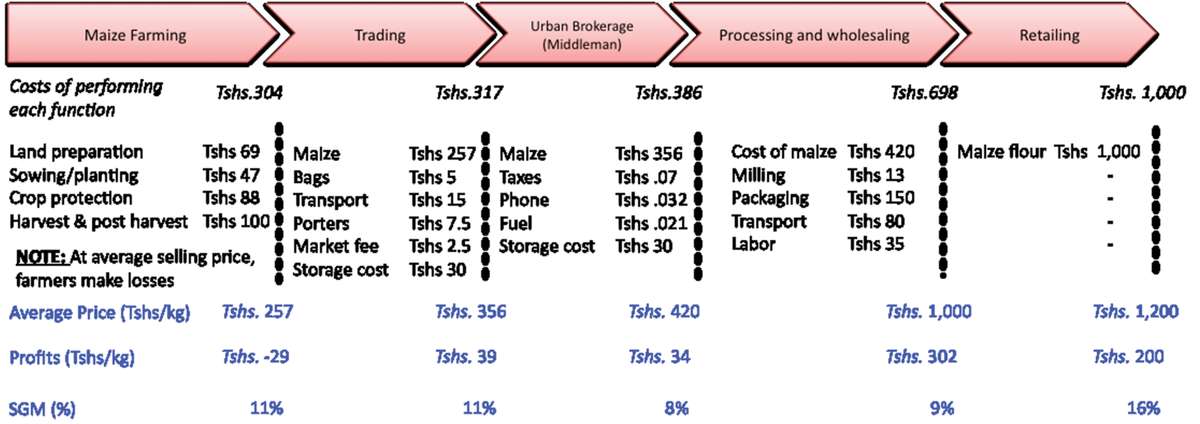

Figures 1 and 2 represent simplified value chain maps for maize flour and analysis of cost and profitability along the chain respectively.

Figure 1. Simplified value chain map for maize flour. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012.

Figure 1. Simplified value chain map for maize flour. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012.

Figure 2. Analysis of costs and profitability along maize flour value chain. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

Figure 2. Analysis of costs and profitability along maize flour value chain. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

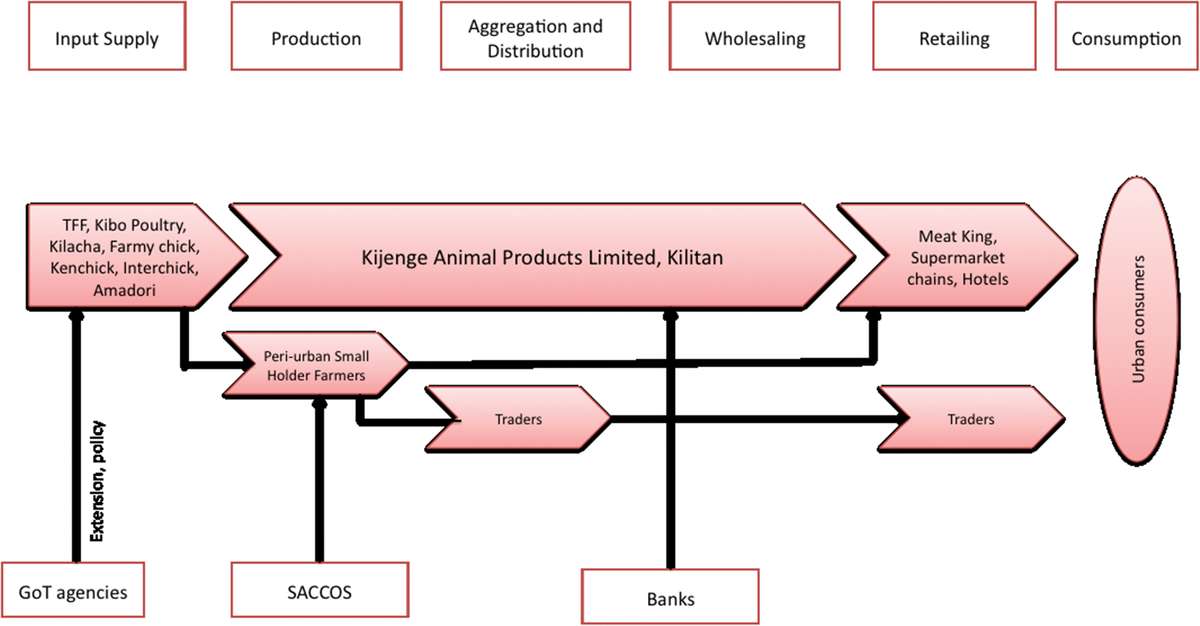

Figure 3 and 4 presents the same for poultry value chain.

Figure 3. Value chain map for poultry meat. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

Figure 3. Value chain map for poultry meat. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

Figure 4. Analysis of cost and profitability along the value chain of chicken meat. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

Figure 4. Analysis of cost and profitability along the value chain of chicken meat. Source: MMA value chain study, 2012

Once an understanding of the value chain is achieved, the next step is identifying objectives for intervention and intervention strategies. Examples of objectives for interventions can be to re-distribute the gains to farmers as signified by Simplified Gross Margins (SGM) in Figure 2, increase efficiency and reduce costs along the chain or increase inclusiveness and potential benefits of SHF.

Inclusiveness and farmers’ participation along value chains

SHFs can participate in value chains in many different ways. These forms of participation can be assessed according to two broad dimensions:

(a) the type of activities that farmers undertake in the chain; and

(b) the involvement of farmers in the chain governance.

Farmers can choose to focus only on crop production, which includes land preparation, growing the crop, and harvesting when the crop is mature. But to increase value of their products, they may also be involved in other activities in the chain such as drying their crop, sorting and grading, processing, transporting and trading. Farmers can demand higher prices for products of higher value and hence increase their net earnings from undertaking chain activities. In addition, when farmers move upwards along the value chain in the functions they perform (e.g. process their products, or transport them to the market), they are able to reduce the number of actors along the chain and possibly improve their profit margins.

Value chains imply repetitiveness of linkage interactions. Governance ensures that interactions between firms along a value chain exhibit some reflection of organization rather than being random. Governance involves setting parameters requiring product, process and logistic qualification, and coordination of actors to ensure that they are able to meet the set parameters. Chain governance includes aspects such as definition of grades and standards, targeting of consumers, management of innovations and so on. The underlying objective of chain governance is to produce what the market wants and is willing to pay a premium price for. Farmers may be excluded from decision-making in the chains, or they may actively design and steer the production process and forms of cooperation in the value chain. Interventions targeting increasing gains to farmers often would like to have farmers included in chain governance. This is because, when farmers are involved in governance, it is easier to harness their willingness, cooperation and participation to work towards meeting the set parameters. Also, farmers are able to benefit from premium prices, which the market is able to pay when the set standards are met, hence increasing their returns from chain participation.

It should be noted that farmer’s participation in value chains does not always guarantee that they benefit from their participation. In addition to farmer’s participation, companies (i.e. chain leaders) of the value chains in which farmers are involved need to proactively include farmers. A company can include farmers through deliberately sourcing inputs from them and also making farmers part of its market, by designing and packaging products (e.g. in small units) in such a way that low income farmers can purchase and hence become part of the market for products which they contribute inputs. Facilitating farmers’ linkages to value chains and to markets and engaging chain leaders to meaningfully include farmers can go a long way to increase benefits to farmers and reduce poverty. In some cases, to engage chain actors, the chain facilitator or market linkage facilitator needs to come up with attractive business propositions for inclusiveness.

Value chains and market linkages

Value Chain Development (VCD), usually undertaken through a number of upgrading strategies involves deliberate processes aimed at increasing economic benefits to actors along the chain. The process and function of upgrading aims to create efficiencies and competitiveness along the chain, while product and market upgrading aims to make products meet market requirements and enhance linkages to better markets respectively. Market linkage therefore is a significant component of VCD, especially when viewed from the perspective of market upgrading.

Market linkages come in different categories, some formal (with contracts signed between buyers and suppliers) and some informal, without contracts but mostly based on trust. Also, some linkages are only for markets of outputs, while others are only for inputs. Most literature documents contract farming as one of the market linkage approaches available. Contract farming links farmers to both farm inputs and outputs markets. In its most informal way, market linkage can also be defined to include empowering farmers, by way of giving them the market information, which enhances their bargaining formation in the market. Although questions concerning relevance and timeliness of market information provided through information and communications technology (ICT) still need to be addressed, ICT is currently widely applied to provide market information to farmers.

Benefits of linking SHF to markets

There are numerous benefits for SHFs being linked to markets. The benefits are outline below.

- Market discovery and transaction costs are reduced.

- New commercial or credit-related contacts become possible; exchanges can be depended upon to evaluate the risks of potential clients.

- Information is generated and shared on current and future market opportunities.

- Market risks are reduced, such as vetting by brokers, blacklisting unreliable buyers and sellers, and possible recourse to arbitration in case of contractual problems.

- Risks related to product quality are reduced, because exchanges can define quality and grading standards, and actors may also offer their own facilities for grading

Challenges of linking SHF to markets

Stakeholders promoting both crop and animal value chains and market linkages face a number of challenges, which are summarized below.

In crop production, the main challenges faced by small-scale farmers are associated with knowledge, inadequate agronomic training, a clear understanding of the value chain, market information, low economies of scale in business, marketing and technical skills, and small size prohibiting access to important services critical for developing their enterprises such as inputs and finance, weak bargaining position and limited market access.

- As a result their most likely “business” partners are middlemen who perpetuate dependency for market access and for finance.

- Direct private investment both in production, processing, and marketing agricultural commodities is still very small and often beneath the critical minimum required.

- Information on prices rarely reaches smallholders. Thus, they are unable to capture urban markets to enable supply to meet consumer demand.

- There is a highly regulated formal sector with high and multiple taxation

- Supermarkets are rapidly dominating food sales worldwide. Supermarket supply chains require high levels of coordination between producers, processors and markets, and continuous supply whereas most small-scale farmers produce seasonally.

In the field of animal production, the main challenges faced by small-scale livestock producers are similarly associated with knowledge, inadequate livestock or livestock product training, a clear understanding of the value chain, market information, economies of scale in business, marketing and technical skills, small size prohibiting access to important services critical for developing their enterprises such as inputs and finance, weak bargaining position and limited market access. As a result their most likely “business” partners are middlemen who perpetuate dependency for market access and for finance. Livestock keepers in developing areas typically suffer from a number of constraints such as:

- Lack of improved breeds (local and improved)

- Poor feed quantity and quality

- Uncertain veterinary input supplies (drugs, vaccine, equipment)

- Shortage of genetic materials (AI, bull services, liquid nitrogen, semen)

- Unavailable or expensive milking utensils/equipment

- Poor husbandry and management (shelters, health, feeding, breeding, milk or meat quality)

- High Transportation costs or unavailable

- Lack of storage (cooling) facilities

- Inappropriate processing / packing materials

- Widely scattered collection centers for milk

- Poor market information

- High cost of inputs (unfair selling price)

- Poor market infrastructures

- Poor quality products and lack of capacity to fulfill established standards

- Highly regulated formal sector; high and multiple taxation

Value chain development is a process, not a one shot intervention, that should start or continue developing where basic conditions are fairly fulfilled. Products of traditional farming are increasingly losing local market opportunities as well as larger national and international market opportunities. There is ample evidence where local products have already lost their competitiveness in price compared with high-quality imported products in their respective local markets. This paper calls stakeholders in smallholder development among the poor to create synergy among different actors to safeguard traditional markets and enter new markets, to increase sales volumes, reduce transaction costs (e.g., searching for information, individual travel to markets, time involved to sell, etc.) and increase margins of profit. Linking SHF to markets, involves facilitating their access to actors in commodity value chains and assisting them to obtain the best possible prices for produce and inputs.

Value Chain Approach

The value chain approach can address a number of challenges to link farmers to markets for inputs and outputs. The range of services and products in a value chain that can potentially add value are huge and include:

- Input supplies (seeds, livestock, fertilizers, land, water, labor, agric. equipment, other agric. supplies, etc.)

- Market information (prices, trends, buyers, suppliers)

- Financial services (such as credit, savings or insurance, formal & informal sector finance)

- Transport services

- Quality assurance - monitoring and accreditation

- Support for product development and diversification

The role of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) in market linkage

The extended term ICT encompasses information and also communication technologies. ICT is often used as an extended synonym for Information Technology (IT), but is a more specific term that stresses the role of unified communications and the integration of telecommunications (telephone lines and wireless signals), computers as well as necessary enterprise software, storage, and audio-visual systems, which enable users to access, store, transmit, and manipulate information.

Where market discovery costs and transaction costs are high, market information is asymmetric and provided mainly by traders who already have vested interests in transactions. In such situations, where payment mechanisms are insecure and extension services are inadequate, the use of ICT can be handy to address or in some cases act as a stop-gap measure to address inefficiencies in the market systems.

ICTs play an important role in agricultural value chains, with different types of ICT having different strengths and weaknesses when applied to particular interventions. The impacts of ICT are diverse, and they influence market competitiveness in different ways. However, technology should not overshadow the people and institutions involved. While the positive impacts of ICT are being catalogued and discussed, many rural farmers still do not have access to or the capacity to use ICT. Radio programs are one of the best ways to reach those in the rural areas. Cellphones through text and using mobile money services, such as M-PESA, are increasingly making inroads into rural areas. Mobile phones can reach remote areas more effectively than other ICTs such as the internet or fixed phone lines and sometimes, mobile devices are simply the only option available. For people in rural areas, mobile technologies can help to reduce information gaps, and access market information from remote locations, thereby to increase trade, reduce travel costs, and to receive education and notices of weather patterns.

Conclusion

Supporting and empowering value chains, management skills and technical expertise, requires not just a new approach by smallholders and the market, but a significant change in the role and actions of the chain actors, both primary and secondary, including development agencies and the general public. Entrepreneurial capacities of small farmers must be strengthened to understand and to meet in a timely way the quality and safety requirements of the supply chain. Capacity building must address start-up, financing and development of small-to-medium agro-processing enterprises to enhance process and function upgrading. In developing economies, the ‘informal sector’ describes the participation of SHF and small businesses, which plays a major role in employment and livelihoods support and plays a major role in sustaining economies. The public can play a part in considering how to foment fair trade along value chains, to advocate for inclusiveness for SHF and small businesses, ensuring an enabling environment so that the needs of the informal sector are addressed.

Value chain development programs should facilitate and support SHF to do business. Development actors need to strengthen skills to enable rural innovation so that small scale farmers and livestock keepers can find and manage markets, access value-adding technologies, achieve improved links with other actors and organize effective support services.

Motivating farmers to form associations is a positive means to create opportunities for value addition, enable achievement of economies of scale and enabling achievement of a collective bargaining power. In addition, in this current era where extension services are inadequate, it is cost effective to deliver training and other services to groups of farmers as opposed to individuals scattered over a wide geographical area.

In light of the proliferation of assortment of ICT solutions, there have been a number of ICT applications to agriculture and livestock development which have been used to provide extension services to farmers. For instance, iCow, an initiative of Green Dreams TECH Ltd, based in Kenya uses SMS (text message) and voice-based mobile phone application, to provide solutions which enable small scale dairy farmers to track the estrus stages of their cows, while giving them valuable tips on cow breeding, animal nutrition, milk production efficiency and gestation. iCow prompts farmers on vital days of cows’ gestation period, helps farmers find the nearest vet and artificial insemination (AI) providers, collects and stores farmer milk and breeding records and sends information to farmers on best dairy practices. More research is recommended into application of ICT to enable extension and market information provision, and scaling out of practical solutions.

References and internet links

- A handbook for Value Chain Research, Prepared for the IDRC by Raphael Kaplinsky and Mike Morris (2000)

- Building Empowering Value Chains: Integrating Smallholders into the New Opportunities in Agriculture IFAD and WB Presentation to ECOSOC High Level Segment Thematic Debate on Rural Development 3 July 2008

- CTA Practical Guide Series, No 16 – Practicing Smallholder Farmers to Markets

- Smallholder dairy production and marketing – Opportunities and constraints. Proceedings of a South – South workshop held at Nattional Dairy Developmant Board (NDDB) Anand, India, 13-16 March 2001.