Mtangazaji: Allan Hrushka

Tukio: EIAC 2024 (13-11-2024)

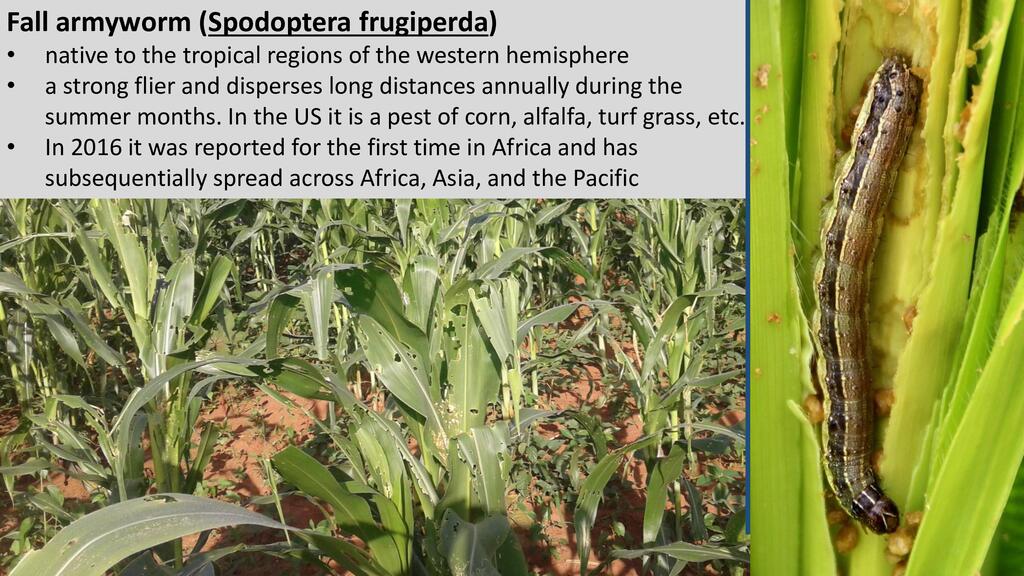

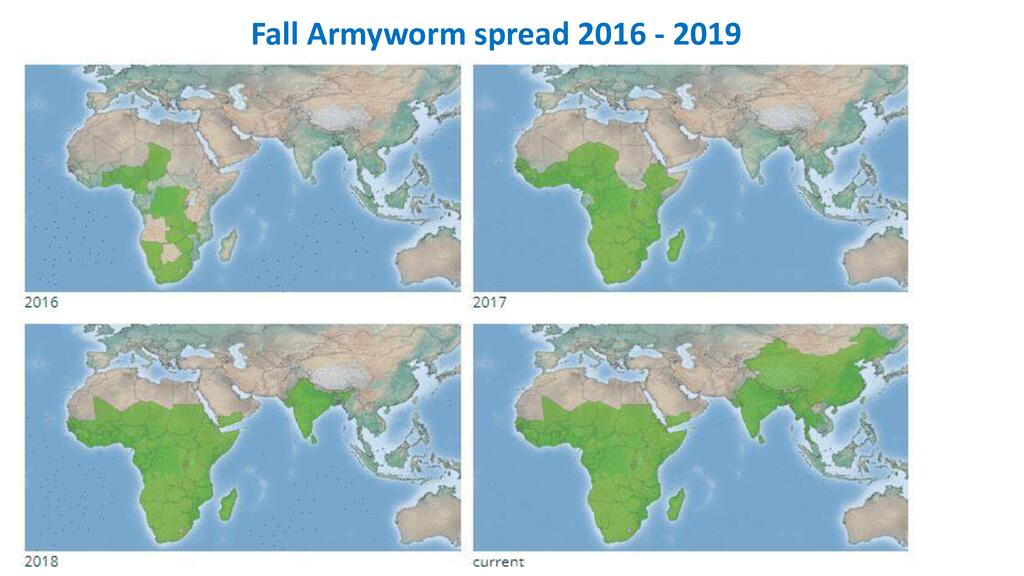

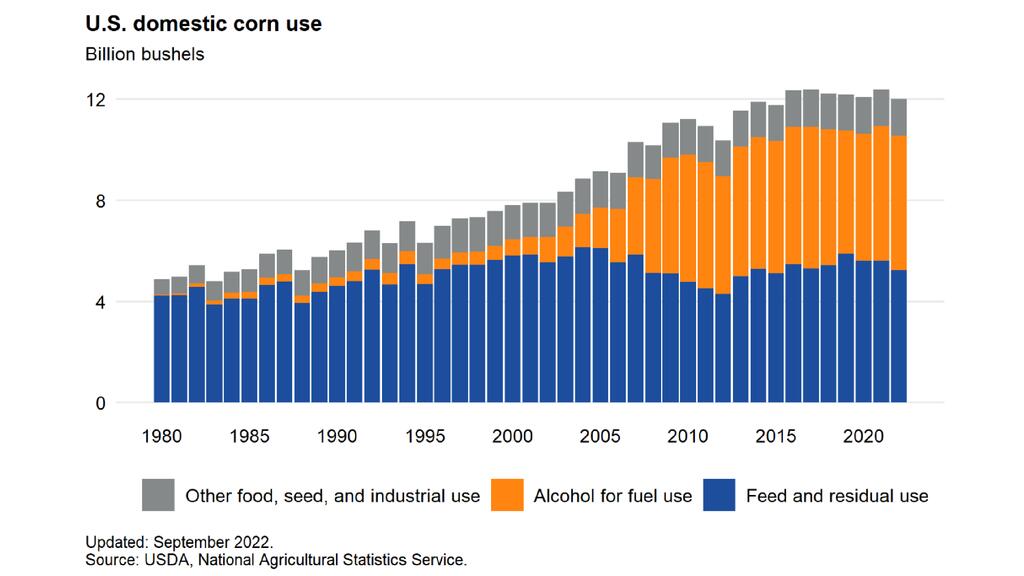

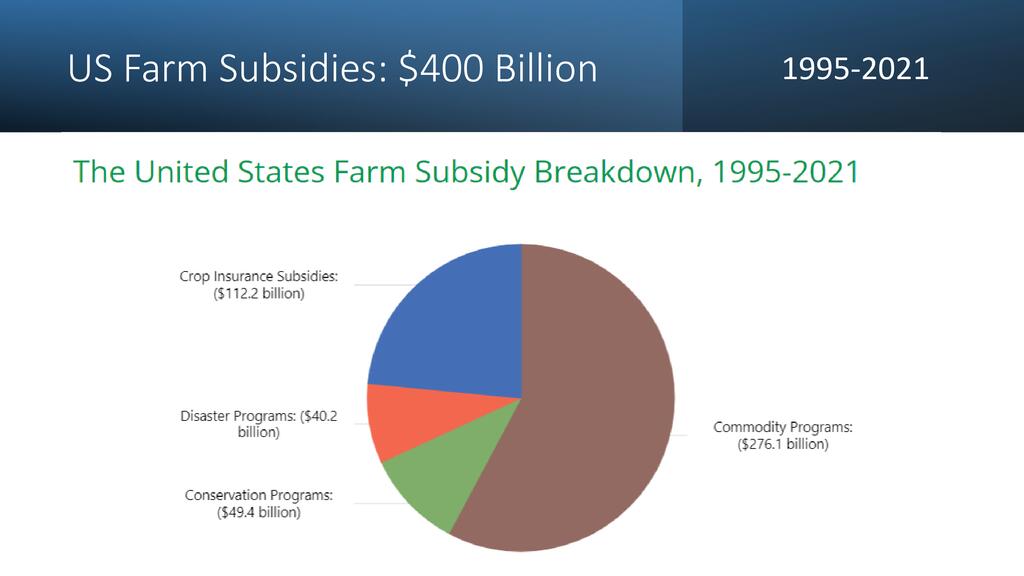

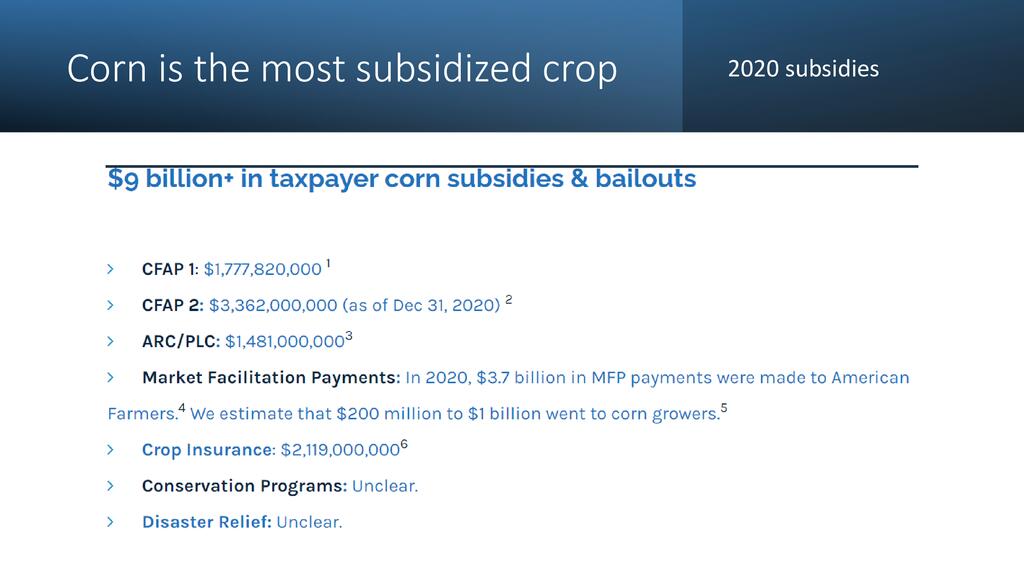

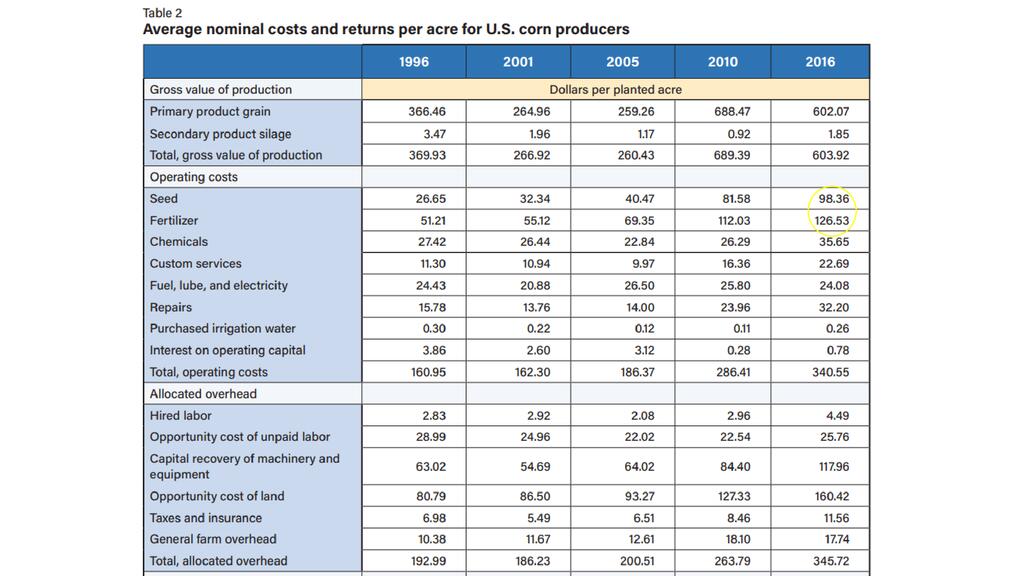

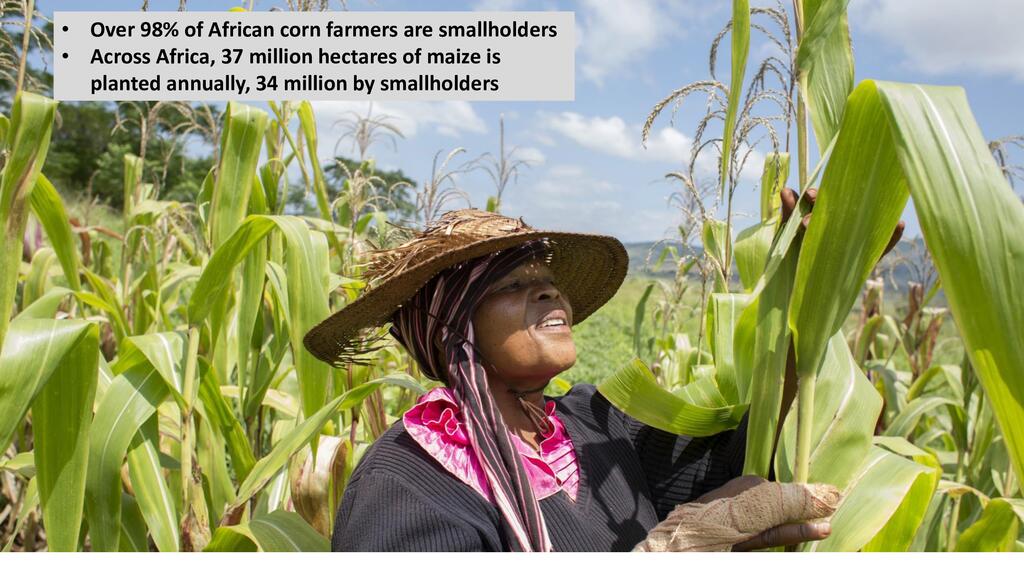

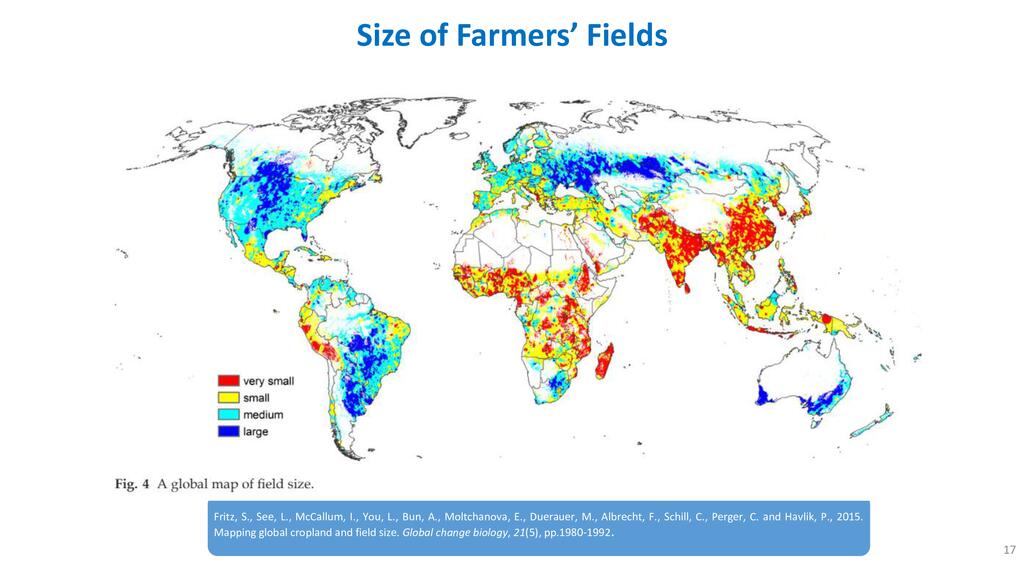

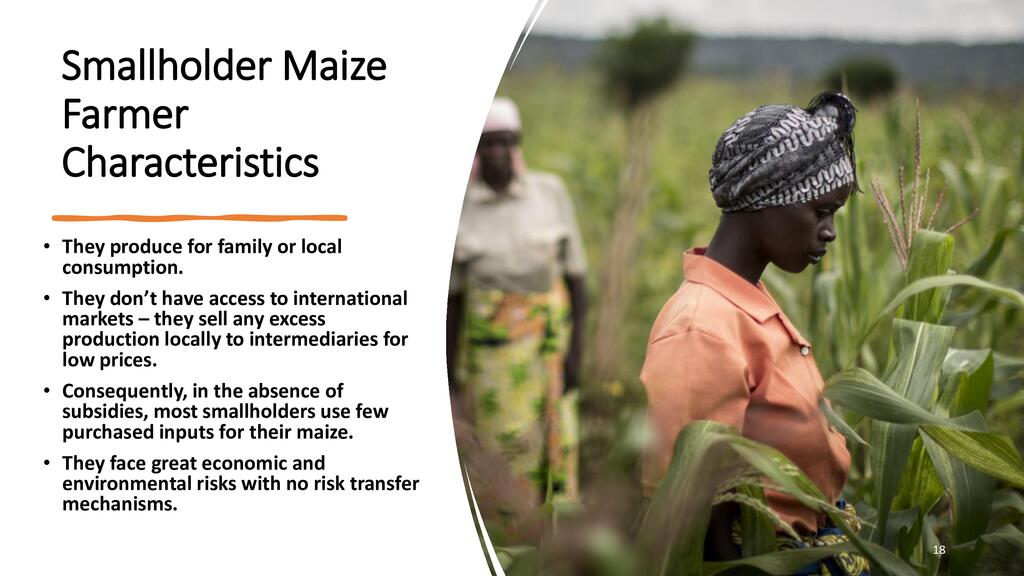

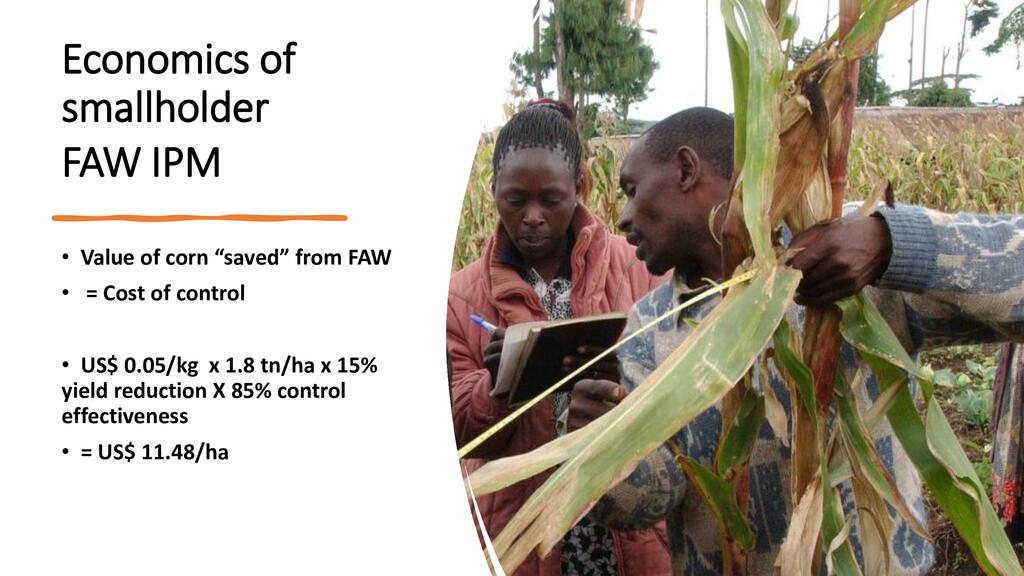

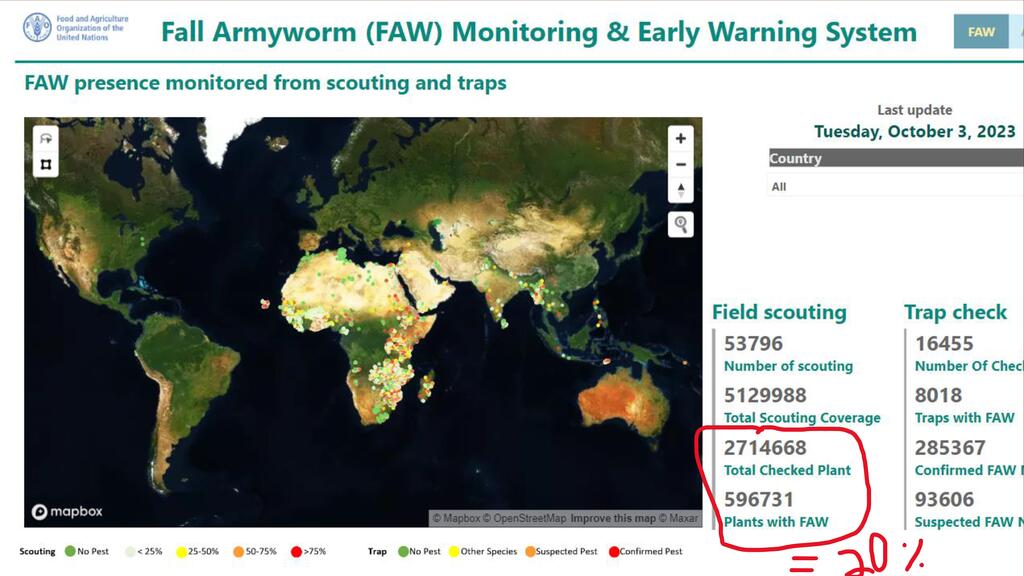

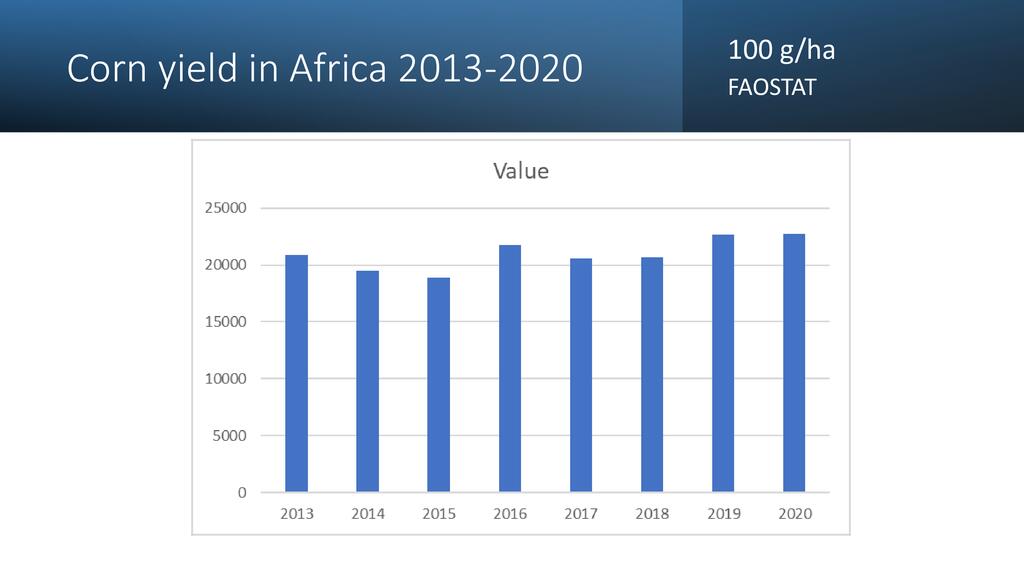

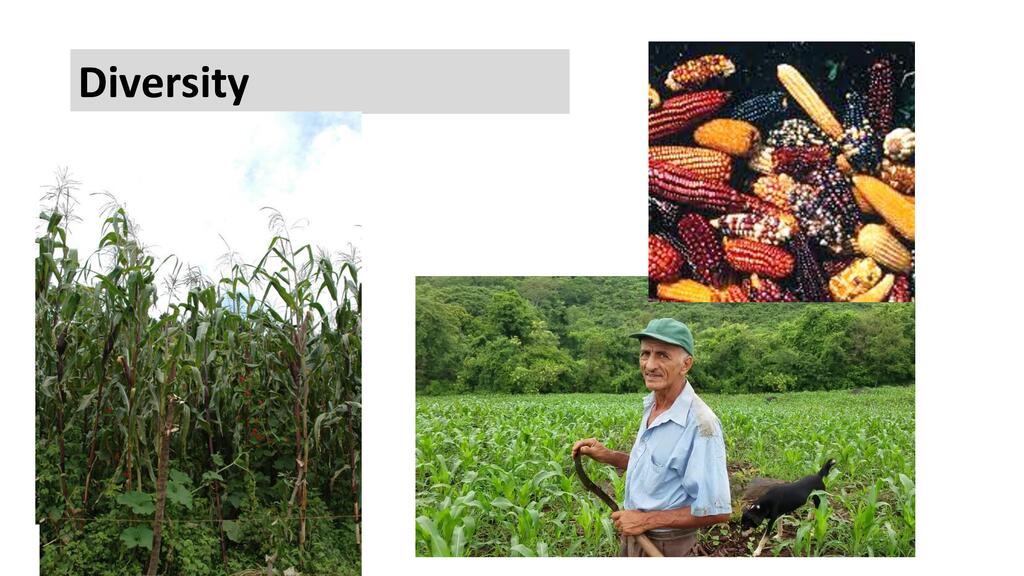

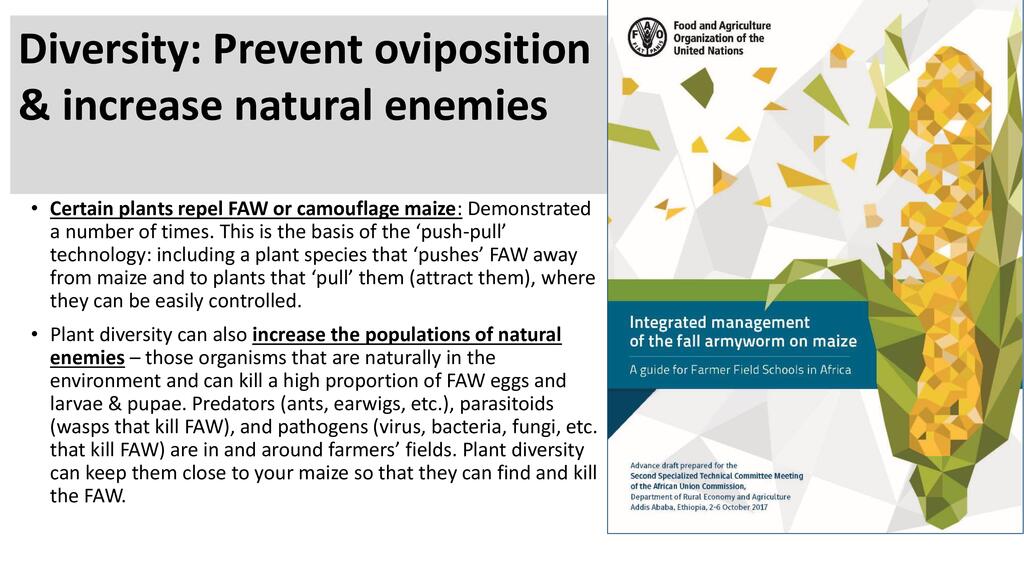

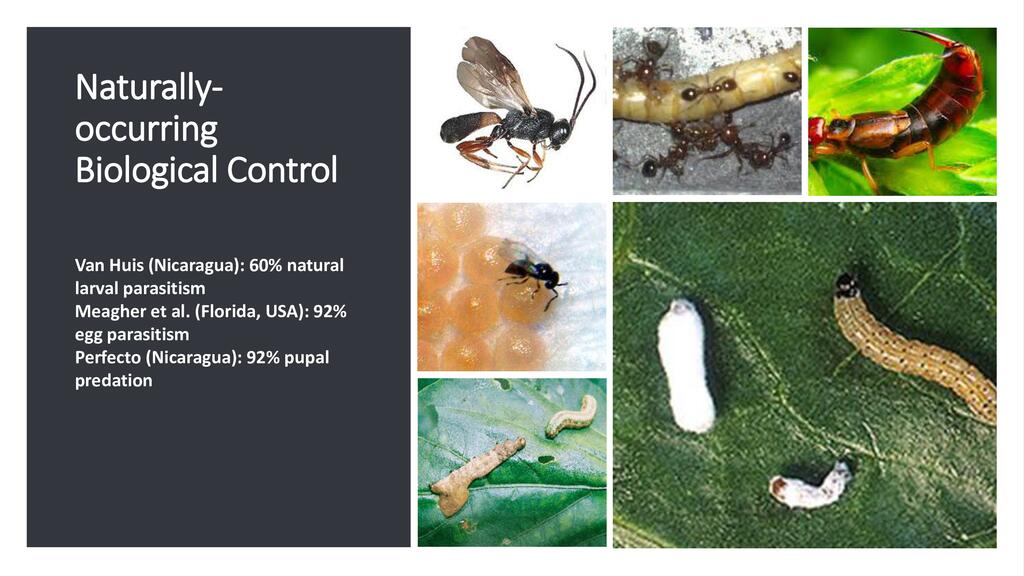

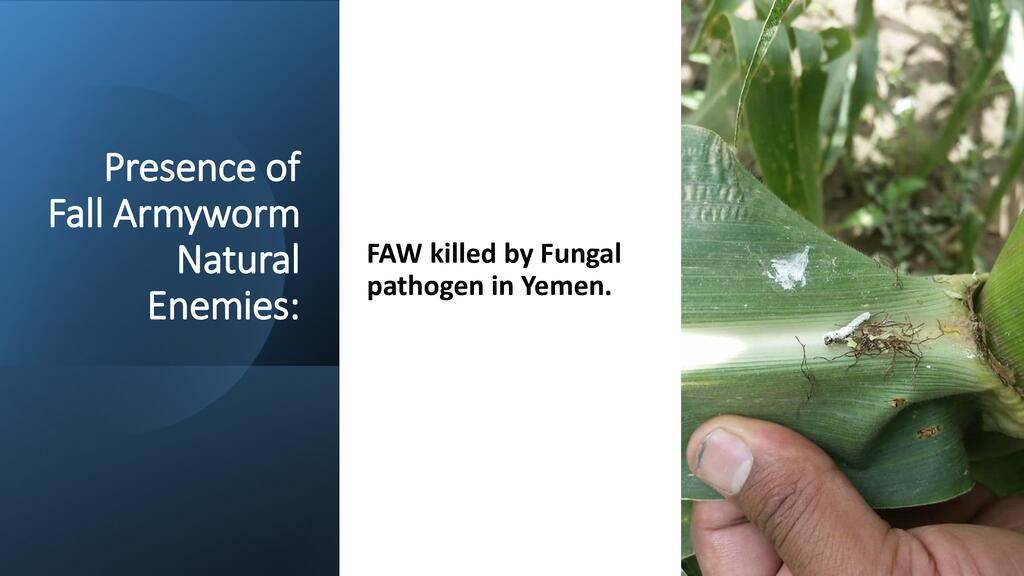

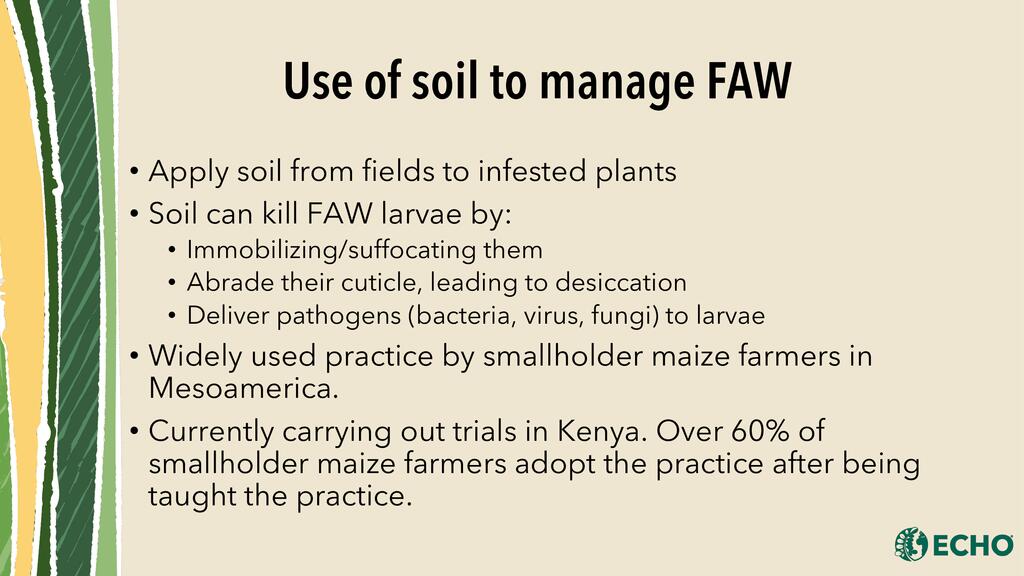

The overwhelming majority of global maize farmers are smallholders, usually producing less than two acres of maize to feed their families. However, most global maize production technology has been made for large-scale farmers who grow their maize for international markets where maize is used for animal feed, converted into ethanol, or used as ingredients in processed foods. These farmers often receive subsidies from their governments, including minimum price guarantees and subsidized crop insurance. This dramatically different economic and production context means that the technologies and costs that make sense for large-scale, subsidized farmers often don’t make sense for smallholder farmers. Smallholder farmers require different approaches and technologies, not attempts at “technology transfer”. Since fall armyworm (FAW) reached Africa in 2016 FAO and other organizations have been funding local scientists at local universities and national programs, in partnership with local scientists and institutions to find solutions for the management of FAW that are effective, safe, low-cost, and accessible to smallholder maize farmers. This research and practice continue to elucidate the agroecology of small, usually diversified maize fields that are typical of smallholders. Diverse maize fields are rich ecosystems of natural chemicals and organisms that can be used to successfully manage FAW. One very promising tactic is the use of soil from the maize fields, applied directly into the whorl. Ongoing studies show that placing a handful of soil into maize plants with active FAW infestation can be a highly effective, safe, low-cost, and accessible control tactic for smallholder maize farmers.