- Ethiopian Kale Gives Seed in the Tropics

- Katuk and False Roselle

- Kiwifruit in the Tropics

- Tropical Lettuce

- Lettuce Varieties Suited for Hot Areas

- Luffa Gourd

- Malabar Spinach

- Moringa Report

- New Zealand Spinach Growing Hints

- Okinawa 'Purple' Spinach

- African Okra variety in ECHO's Seedbank

- Onions in the Tropics and Subtropics

ETHIOPIAN KALE GIVES SEED IN THE TROPICS. Kale is the favorite green in my family, both for its taste, texture and nutrition. A drawback is that it does not set seed in the tropics. Dr. Warwick Kerr in Brazil sent us seed of the "Ethiopian kale" (Brassica carinata) which does produce seed. According to Cornucopia, "tender leaves and young stems, up to 12 inches high, can be eaten raw in salads. Older leaves and stems are cooked and served like collards or mustard. The inflorescence may be used as a broccoli-like vegetable. Seeds are the source of an edible oil." This kale has grown exceptionally at ECHO for years, and we have received many other positive reports on this hardy, productive plant from around the world. It grew so well in missionary Mark Vogan's gardens in Ecuador that he incorporated it into his rabbit feeding system and allows it to grow as a "weed" wherever it sprouts for this purpose.

KATUK (Sauropus androgynus) is one of the staple vegetables in Borneo, where it is sometimes grown as an edible hedge. It is one of our favorite summertime greens at ECHO. All greens, whether cooked or raw, are important nutritionally  and can be tasty in various dishes. However, few are known especially for their unique taste. Katuk is delicious; after chewing a raw leaf or stem tip a few times you can notice a pea-like or nutty flavor. The leaves can be quickly stripped from the stem by pulling it between your fingers. Tender tips, leaves, flowers, and small fruits are eaten.

and can be tasty in various dishes. However, few are known especially for their unique taste. Katuk is delicious; after chewing a raw leaf or stem tip a few times you can notice a pea-like or nutty flavor. The leaves can be quickly stripped from the stem by pulling it between your fingers. Tender tips, leaves, flowers, and small fruits are eaten.

There is another use for katuk in Borneo. By using plenty of fertilizer and irrigation and a bit of shade, they are able to make the tips grow very quickly. The top 5 inches (13 cm) are harvested (there will be only few leaves) and sold to the finest restaurants. I ordered them at the Hilton Hotel in Borneo then watched as they were cooked. The bottom inch was discarded to ensure only tender tips would be prepared and the remaining 4 inches were cut in two. These were then stir fried for perhaps 60 seconds. They can be eaten raw as well. Malaysian Borneo hopes to export these to Japan as "tropical asparagus." (Of course, it is not really asparagus). A delegate at our Agricultural Missions Conference reported that katuk tips are now being grown and marketed in Hawaii.

Katuk is native to the lowland rain forest understory and prefers a hot, humid climate. It will grow in shade or full sun, and it tolerates occasional flooding and acidic soils. Under ideal conditions, it can grow up to 1.5 m per month. However, stem diameter does not grow apace with length and it soon gets so tall that it falls over, earning its description in Edible Leaves of the Tropics as "an awkward plant." In cultivation, it must be regularly trimmed for optimal production of new shoots. Be sure to keep it pruned to between 3-6 feet (1-2 m) high.

Plant about 2-3 feet apart in full sun or partial shade. Because they use shade cloth in Borneo for producing tender tips, I grow it under the eaves on the north end of my house. An additional benefit here is that plenty of water will fall on the plants from the roof even after a light rain and it will get only filtered light. Some people recommend katuk for alley cropping systems with nitrogen-fixing trees. We have had no disease or insect problems at ECHO, although slugs are reportedly a problem among new cuttings or seedlings in some areas. Katuk will produce abundantly throughout the warm months. During the coldest 2-3 months of winter at ECHO, plants may appear a bit sickly, stop growing, and be less tasty until new growth resumes with warm weather.

Katuk is easily propagated by moderately woody cuttings (20-30 cm long, with at least two nodes), though they can be slow to establish. If you visit ECHO on your way to the field, you can pick up some cuttings. During short days, there will be a lot of small blossoms underneath the stem, which can be stripped right along with the leaves and cooked. Our katuk, vegetatively propagated for some time, flowered but did not produce seed until we acquired plants from a different source (when they produced seed immediately); it is possible that separate plants are required for seed production or some varieties are selected for or against seed production. ECHO seedbank intern Jim Richard collected seed in December and allowed it to air dry until it was planted in January. It germinated in about 3 months. Since 1996 was the first year we successfully grew katuk from seed, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to distribute it from our seedbank, but if you are willing to wait you can request seed from ECHO and we will put your name on a waiting list until seeds are ready in January.

According to Cory Thede in Brazil, "Katuk and false roselle (Hibiscus acetosella) are easy to start from cuttings of any part of the plant, old or new growth (even in the dry season). Strip off most leaves and put the cutting directly into the ground under partial shade. They are survivors and palatable to most people. The false roselle was especially popular because of the red-purple color and sour, tangy flavor. Katuk is a light producer of greens compared to others I grew." [ECHO also has seed of false roselle.]

KIWIFRUIT (ACTINIDIA DELICIOSA) IN THE TROPICS. I have always discouraged people who wrote from the tropics asking where they could obtain plants of this New Zealand vining fruit. It is definitely not a tropical fruit. For example, the newsletter of the Rare Fruit Council International in Florida in 1987 says that kiwi has been tried all over Florida and has never been successful. (The plants grow well, but do not fruit.) So I assumed that it would be even more difficult in the tropics.

A few years ago I toured the farm of my friend Victor Wynne, at just over 2000 meters in Haiti. To my surprise there were vigorous kiwifruit vines and, hanging under them, were several kiwifruit. That does not mean you should all rush off your orders for kiwi plants. First of all, he planted them in 1983 (variety 'Abbott') and later almost tore them out when they never bore. In 1988, he got a few fruit. Though there were several more fruit after the sixth year, it was not at all clear if there was any commercial potential. That will all depend upon how heavily and reliably they bear.

There is a fantastic annual networking newsletter to promote cooperation and communication among kiwifruit enthusiasts, called the Kiwifruit Enthusiasts Journal. Each issue is like a large magazine, the 1993 issue (#6) having 193 pages. It is a grassroots newsletter, with over 100 people from 12 countries contributing to one issue we saw. Advertisements provide sources for the plants. They do not take subscriptions because its publication frequency depends on who volunteers to help. For the next issue or a back issue send US$14.95 plus shipping ($2.25 in USA; $3.75 overseas surface; $11.25 airmail) to Friends of the Trees, P.O. Box 4469, Bellingham, WA 98227, USA; tel/fax 360/738-4972; e-mail trees@pacificrim.net; http://www.pacificrim.net/~trees.

Much of the work seems to be toward extending the range in which kiwifruit can be grown, especially looking for cold-hardiness. To help you evaluate the chances in your area, here are the countries where commercial plantings exist, according to the Enthusiasts newsletter: New Zealand (half of all production), California in the USA, France, Italy, Japan, Israel, Chile, Greece, Yugoslavia, Hungary, Korea, Australia, Spain, and British Columbia in Canada. The newsletter says the coming rage will be smooth-skinned kiwifruit and colored kiwifruit (red, yellow and purple skinned).

Michael Pilarski, editor of the kiwifruit journal, sent us this summary on varieties: "Kiwifruit can be grown in the tropics and subtropics in high elevation areas which receive winter cold periods. The 'Hayward' variety most often seen in the marketplace is one of the poorest choices. The best varieties for low chill areas identified to date by the KEJ network are 'Elmwood' (large-fruited, early bearing); 'Vincent'; 'Dexter' (from Australia); and 'Koryoku' (from Japan). Even more likely of success are the species: Actinidia chinensis (large-fruited, smooth-skinned and sweeter than A. deliciosa) and A. melanandra (small-fruited, red, sweet fruit)." He is probably the best contact on the subject (see above for Friends of the Trees address).

Kiwifruit is no longer the "get rich quick" crop it once was; it is "over-planted" and prices are dropping on the international market. Some recent plantings made with the help of high-interest loans are going bankrupt. If your country does not produce  kiwifruit and your region has just the right microclimate so that you have any chance of producing, kiwifruit might be a long shot for a high-value home market. It is not for most of our network and I would not even think of participating in the export market from a country marginally suited to the crop. If you do try kiwifruit, be sure to let us and Michael Pilarski know the results.

kiwifruit and your region has just the right microclimate so that you have any chance of producing, kiwifruit might be a long shot for a high-value home market. It is not for most of our network and I would not even think of participating in the export market from a country marginally suited to the crop. If you do try kiwifruit, be sure to let us and Michael Pilarski know the results.

Dr. Campbell gave the following comments in our video tape series on tropical fruits. Kiwifruit is a fruit of warm temperate climates, not of the cooler subtropics. It needs substantial cooling hours (around 45 deg.F/7 deg.C or cooler). Temperatures in the 50s (deg.F) may have the same effect, but in many more hours. To make matters worse, periods of hot weather during the "cool season" can counteract some of the effect of cool days. When the bearing season arrives, it is important that nighttime temperatures not be too high. (That is presumably why kiwifruit are not a commercial crop in the southeastern part of the United States.) In subtropical mountains suitable conditions might be found, but he speculated that the frequent cloud cover might reduce performance.

Here are some other interesting tidbits from the Enthusiast. Kiwifruit is especially nutritious because the seeds are eaten. (It is technically a "berry.") A five-ounce kiwifruit has more potassium (450 mg) than a six-inch banana (370 mg). It has almost twice the vitamin C of a medium orange. Avocado is one of the few fruits with a lot of vitamin E; kiwifruit has twice that amount. The skin does not need to be removed (and contains many of the fruit's nutrients). Just scrub off the fuzz with a vegetable brush. In cooked foods, the fuzz virtually disappears and the skin adds a tang and chewable substance not unlike citrus peel. "When pureeing kiwifruit it is important not to over-blend. If the tiny black seeds are crushed, they will turn the drink or soup bitter."

TROPICAL LETTUCE. Dr. Frank Martin gave us our initial start on a tropical lettuce, Lactuca indica, also called Indian lettuce. This has grown well in both the hot, wet summer and the colder winter of southern Florida. During the summer it grows to about 8 feet (2.5 m) high. Winter size is about half that. The rather large leaves can be eaten raw or cooked. According to Dr. Martin's book Edible Leaves of the Tropics, it is commonly grown in the Orient, mainly cooked as greens, but it can be eaten raw. We have found it to be quite disease and insect resistant. It is more bitter than the popular lettuces of temperate regions, though after the first bite the bitterness is little noticed. After cooking or when served with vinegar the bitterness is not present. Some local friends have become quite excited about it. Bonnie and I use it as a lettuce only when the weather is too hot for regular lettuce, but it fills a real void during those hot periods. It is good cooked by itself or mixed with other edible leaves at any time. If you are in a region where lettuce does not grow well, write for a free packet of seed. We will be interested to see how it does in different areas. It might even be a good lettuce for a rain forest.

LETTUCE (LACTUCA SATIVA) VARIETIES SUITED FOR HOT AREAS. Montello. Our readers in the warm lowlands probably have a problem growing lettuce. I attended the combined annual meeting of the Caribbean Food Crops Society and the tropical region of the American Society of Horticultural Sciences in Trinidad. One of the field trips was to visit a commercial lettuce operation. They were growing very nice lettuce for the hotel and other markets, even though the location appeared to be near sea level. The variety was 'Montello.' The plants were under shade cloth in long narrow bags filled with artificial potting mix and carefully watered. They looked beautiful, though I did not get to open up a head. They may not be as tightly packed as iceberg lettuce grown in a temperate region, but the quality is apparently quite acceptable. It has large, dark green heads and reportedly ships well. Timing is crucial because the plants do go on to bolt. We saw one bolted planting that had apparently matured when the market could not take them all. Rhine Fecho, who has started an Episcopalian agricultural school in Haiti, told me that he was growing this same variety in full sun, in soil, in August near sea level.

ECHO has purchased 'Montello' lettuce seed and will send a small trial packet to our overseas readers who wish to try it. You should be able to increase your own seed (or purchase in bulk from Twilley Seeds, P.O. Box 65, Trevose, PA 19053-0065, USA). Bend seed heads into bags and shake off the mature seed. We have found that the fluff can be removed from the seed by placing it in a jar and stirring vigorously with a fork. Alternatively, harvest plants when 30-50% of the seeds show white fluff and dry for a few days. Seed can be stored in airtight containers in the tropics for 6 months if dried to 8-10% moisture. (One way to get seeds this dry is to leave them in a closed container with excess desiccant and keep replacing the desiccant with fresh until it remains dry. This is seen easily if you have a small amount of desiccant that turns color when wet. Lacking the indicator, you will have to use your judgment.) In a cool dry place (refrigerator) it can be stored 6 years.

Roy Danforth wrote from Zaire that the Montello lettuce "is superb. It heads very nicely and is not bitter. It is similar to the iceberg variety. It heads after it has produced a good salad bowl's worth of leaves and produces a lot of good viable seed, which I've started spreading around everywhere." Roy works 3 degrees north of the equator. In our own summer gardens we find it difficult to grow. We have free trial seed packets for third world workers (U.S. readers should request our seed sales list).

Queensland. Pat and Connie Lahr gave us a packet of seed for this lettuce after a visit to Australia. Pat believes it is grown primarily by an association of organic market gardeners. As far as he knows seed is not sold commercially. It is a big leaf lettuce that appears to be exceptionally resistant to bolting. Leaves are large, somewhat resembling a cos-type lettuce, with an attractive yellowish hue. In Australia they say it produces 8 weeks in summer, up to 14 weeks in winter and that it is best to use lower leaves.

My main interest is their apparent resistance to heat. We have not done carefully controlled experiments, but 'Queensland' appears to outlast most of our lettuce varieties when the warm season arrives. Each time we grow it I wonder, "Is this ever going to bolt so we can save seed?" (A key to preventing bolting is to make sure the plants are never water stressed. It might well be that they would bolt quickly if we did not have irrigation.) ECHO produces a small quantity of seed for our network. Be sure to save your own seed if it does well.

Several people wrote concerning their results with 'Queensland' lettuce. Ken Turner in the Philippines says "it was the best of 10 leaf lettuces tested, for ease of growing, durability and taste. I'm impressed. If leaf lettuce could just become an alternative here to head lettuce, this could be a winner. Head lettuce sells for $3 per kg in some months." Victor Sanders wrote, "'Queensland' lettuce does very well here in Haiti (in the mountains of La Gonave). We are getting all the lettuce we need during the dry season. I am growing it [with your rooftop garden methods] but on top of the ground. This method is working well in that it greatly reduces water loss in the soil below."

Maioba is Brazilian in origin, noted as high in vitamin A and resistant to acidic soils. Available from ECHO.

Anuenue is bred for resistance to tip-burning and heading under warm growing conditions. You may purchase it in bulk from the University of Hawaii (Seed Program, Department of Horticulture, 3190 Maile Way, Room 112, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA; they only ship to US addresses; phone 808/956-7890).

LUFFA GOURD (Luffa acutangula--angled and L. cylindrica--smooth; preferred for sponges) is well known in temperate countries for producing "sponges." The plant prefers hot growing seasons and is a productive vegetable in the tropics. Young fruits can be eaten raw or cooked. In Asia, the young leaves, flowers, flower buds, and roasted seeds are all eaten. Immature fruits may be harvested about 2 months after planting, while the mature fruits used for "sponges" require 4-5 months. Submerse mature fruits in water for a week so the fruit disintegrates, then wash and dry the fibers, bleaching with hydrogen peroxide before drying if desired.

MALABAR SPINACH (Basella alba, B. rubra) is a very succulent vine grown throughout the tropics for the young leaves and stems, often used as a potherb. The flavor is mild, and the leaves are somewhat mucilaginous when cooked. They can also be eaten raw. It is tolerant of many soil types. Plant seeds or vine cuttings to establish the plants, and harvest regularly. This is a productive, low-maintenance perennial with few pest problems, although nematode damage is so severe at ECHO that it only thrives in soils high in organic matter.

MORINGA REPORT. Cory Thede in Santarem, Brazil, wrote: "We have a marked dry season of 5 months or so. Moringa (M. oleifera) did well in the city but didn't grow well in infertile rural soils. Maybe calcium from the cement, and possibly other nutrients that accumulate in the city, made the difference. Iguanas are a serious garden pest in the area, and they like it...they try to climb even a young plant to eat the leaves, but it is fragile and they knock it over. The young leaves are easy to prepare for cooking; avoid the tough stems of the older leaves. A moringa hedgerow is a convenient way to assure a steady supply of young leaves." This is a very important, drought-resistant vegetable tree. Be sure to see the chapter on Multipurpose Trees for much more information on moringa.

NEW ZEALAND SPINACH GROWING HINTS from James Gordley in Panama. "I am having great results with New Zealand spinach, Tetragonia tetragonioides. [Ed: This is a popular spinach substitute in hot parts of the USA. Because most seed catalogs carry the seed, ECHO does not. One seed source is Burpee, Warminster, PA 18974, USA.] By tying it up on chicken wire it takes very little space and the leaves are kept off of the ground. Before using the wire I had trouble with mold growing on the underside of the leaves. Not anymore. I also find it helpful to use a straw mulch around the plants, especially during hard tropical rain storms, to keep the leaves from being splashed with mud. The muddy leaves also become diseased. With the mulch and wire, neither are problems. I harvest the leaves and allow the stalk to remain on the wire. Within days new leaves have grown out and one cannot see where the leaves were removed. We clean the leaves then soak for three minutes in a solution of 1 tablespoon of 3% hydrogen peroxide in 1 quart of water. There is no aftertaste from the peroxide."

OKINAWA 'PURPLE' SPINACH (Gynura crepioides) looks similar to a local Brazilian weed--both are purple under the  leaves, but the weed has an upright growth habit and is an annual. The cultivated type, which may be a selected weed, is perennial, branching, and tends to fall over, making a bush. It grows very well and is pest-free. It has a tasty, pine-like flavor and did well in poor soils. Mix it with other vegetables; the unique flavor may be too strong on its own." Cory Thede reports this success from Santarem, Brazil. Cuttings available at ECHO.

leaves, but the weed has an upright growth habit and is an annual. The cultivated type, which may be a selected weed, is perennial, branching, and tends to fall over, making a bush. It grows very well and is pest-free. It has a tasty, pine-like flavor and did well in poor soils. Mix it with other vegetables; the unique flavor may be too strong on its own." Cory Thede reports this success from Santarem, Brazil. Cuttings available at ECHO.

AFRICAN OKRA VARIETY IN ECHO'S SEEDBANK continues to produce when days are short, unlike many okras. The pods are edible to a fairly large size. This variety was much sought after by Haitians when they saw it in full leaf and producing in the Central Plateau in August, when their other okras had died. If okra is already grown in your area, this one may be well worth a trial for comparison.

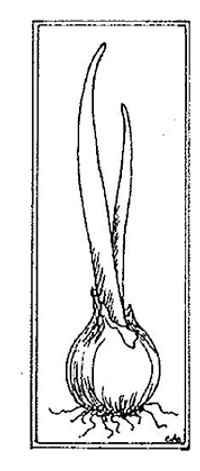

ONIONS IN THE TROPICS AND SUBTROPICS. A case could be made that onions are one of two universal vegetables that are cherished in almost every culture, tomatoes being the other. Both are difficult to grow in many tropical and subtropical climates. Where a vegetable is both popular and difficult to grow, it brings a good price. If a way can be found to grow that crop, both local farmers and consumers will benefit. While attending a horticulture conference in Honduras, Scott Sherman and I had an opportunity to visit with Dr. Lesley Currah. She travels the third world working with onion researchers. The interview follows. Be sure to note the offer of seed for a variety trial of these onions in the chapter on Germplasm.

ONIONS IN THE TROPICS AND SUBTROPICS. A case could be made that onions are one of two universal vegetables that are cherished in almost every culture, tomatoes being the other. Both are difficult to grow in many tropical and subtropical climates. Where a vegetable is both popular and difficult to grow, it brings a good price. If a way can be found to grow that crop, both local farmers and consumers will benefit. While attending a horticulture conference in Honduras, Scott Sherman and I had an opportunity to visit with Dr. Lesley Currah. She travels the third world working with onion researchers. The interview follows. Be sure to note the offer of seed for a variety trial of these onions in the chapter on Germplasm.

Q. Tell us more about the Natural Resources Institute where you work.

A. The NRI is an agency of the British government, the Overseas Development Administration. Their purpose is to use science and technology to help people in third world countries develop using their own natural resources. Help is offered to any country eligible to receive British aid.

Q. What is your assignment?

A. I work in the fruit, vegetable and root section. My current assignment is an evaluation of onion production and storage in low latitudes. A particular interest is to expand onion production in very wet climates and on islands at sea level. Our approach is fourfold.

(1) We are promoting a network of contacts on onions in the tropics through a newsletter called "Onion Newsletter for the Tropics."

(2) We evaluate onion varieties through trials done by collaborators around the world.

(3) We provide training in how to do a trial and interpret the results.

(4) We maintain a gene bank of interesting onion accessions.

Q. Often a development worker from a temperate climate will plant onion seed from home only to find that it only makes "little green onions," no bulbs. Explain what is happening.

A. Onions are very sensitive to day length. The kind of onion that is grown in the higher latitudes requires long day length to form bulbs. When onions are grown during short days it is important to plant what are called "short day onions."

Q. Is there a sharp border between long and short day varieties or are there degrees of short-day-ness?

A. There are several intermediate degrees, which would be common in places like north Texas or Spain. A well organized seed catalog will not just say whether onions are "short" or "long" day varieties. They will organize them under day lengths, e.g. 11-13 hour, 12-14 hour etc. Some varieties like Beth Alpha in Israel go to less than 12 hours. These mature around Christmas. However, because the quality of onions harvested at mid-winter is often inferior, e.g. with more double bulbs, farmers usually want onions to mature as days begin to lengthen but before the rains have started.

Q. What does happen if you plant a long day onion near the equator?

A. As you said, they grow into little green onions. They may thicken a little at the base. They may actually be preferable for producing little green onions because the short day types might begin forming bulbs too soon.

Q. Do onion sets exist for short day onions?

A. Many in the tropics use the set system to get onions going near the end of the rainy season in order to extend the onion harvest forward in time. Probably 30% of the onions in Bangladesh are grown that way. Sets are commercially available in Zimbabwe. However, the quality of onions grown from sets can be inferior, for example with more double bulbs.

Q. How would a farmer make his/her own sets?

A. Just as the hot season is starting, sow seeds at a very close spacing. Do not thin the onions. Harvest at 1/2 inch (1.25 cm) diameter or else they will bolt. If they are sufficiently crowded and if it is well past the day length where the variety would normally bulb, they will die down naturally. It may take a few seasons of trial and error to get it right. Keep the sets in an airy, warm place, such as just under the rafters.

Q. Under what conditions might a farmer be able to save his/her own onion seed?

A. This is difficult. You need a variety that will easily bolt (send up a flower stalk) the second year. You do not want any variety that bolts the first year because that trait would create havoc in your harvest. Select bulbs from the best onions and store until the next season. Timing then becomes important. If you plant too soon while daily temperatures are increasing they may go into bulbing mode and split rather than flower. Wait to plant the bulbs until the average daily temperatures have started decreasing. The stalk gets a lot of diseases so, unless it is very dry, you may need to spray a lot.

Q. What do you look for in a variety trial?

A. You would want most varieties in your trial to be acceptable to local people. If onions are eaten raw, you want varieties which are mild; if cooked, pungent onions that store well. The pungency, by the way, depends not only on the variety of onion but also on how much sulfur is in the soil. You would want to look for onions where a high percentage of the harvested bulbs are marketable and where the bulbs store well. Even the shape and color may affect marketability and price.

Q. How should onions be stored?

A. We are writing a bulletin on storing onions in the tropics. The humidity should be about 75% and the temperature 25-30øC. If the temperatures drop much below 18øC the onions may begin to sprout. For example, in Zimbabwe we found that stored onions began sprouting when evening temperatures dropped to 15øC. This is somewhat dependent upon variety, but only to a limited degree. Light is not a very important factor. Light may cause some fading of red onions on the surface only. Light can also cause some green color to develop in white onions.

Q. Do short day onions store reasonably well?

A. Yes, but there is room for improvement. The Israelis have been working to select grano and granex types that will store for a long time. The factors they select for are ability of the bulb to go into a good dormant period and qualities in the skin that will protect the bulb. Their varieties are being tested all over the tropics.

Q. I notice a lot of short day onions named "grano" or "granex," followed by a number. What are these?

A. Texas grano onions came from onions in Spain which over-winter well in the field, but have poor storage characteristics in general. The granex series is hybrid, the grano open-pollinated (non-hybrid).

Q. This brings up an important question. If you are working where it is possible to produce your own onion seed, would it be a big mistake to save seed from a hybrid onion?

A. No, if you are prepared to do a little selection, and if the hybrid is much better than the locally available varieties, you might end up ahead. For example, in India the Pusa Ratnar variety came from the red granex hybrid. You might have some problems with male sterility in early generations.

Q. How are onions pollinated?

A. Onion pollen is sticky, so there is not much wind pollination. They are pollinated by insects, such as honeybees. Some seed producers throw dead chickens in the field to attract blow flies. Some crawling insects are also pollinators.

Q. Some of the special seeds that ECHO distributes have come from members of our overseas network. Is there any way in which they might help you?

A. I am interested in any traditionally maintained, locally grown onion. However, the needs of our seed bank require that we obtain about 50 g of any new accession. England is so far north that we are unable to increase the seed ourselves. If someone has an onion that might be of interest, they should first write and tell me as much about it as they can, and why they value the onion. My address is Lesley Currah, Horticulture Research International, Wellesbourne, Warwick, CV35 9EF, UK.