[Eric Toensmeier is a long-time friend of ECHO. He has researched and promoted perennial vegetables for more than two decades, and written about them in books such as Paradise Lot and Perennial Vegetables. Toensmeier recently coauthored a paper with Rafter Ferguson and Mamta Mehra, called “Perennial Vegetables: A neglected resource for biodiversity, carbon sequestration, and nutrition” [http://edn.link/tones]. Here he summarizes the article’s information about perennial vegetables’ potential contribution to human nutrition.]

Perennial vegetables are a class of crops with great potential to address challenges like dietary deficiencies, lack of crop biodiversity, and climate change. Though some individual plant species have received significant attention (e.g. moringa), as a class, perennial vegetables have been largely overlooked. In this article, I provide an overview of perennial vegetables, focusing on their contribution to human nutrition.

Perennial Vegetables Defined

Perennials are plants that live for three years or more. Perennial vegetables (PVs) include trees and shrubs, cacti and succulents, palms and bamboos, and vines (both woody and herbaceous [plants with soft instead of woody tissue]). PVs also include herbaceous plants like ferns, grasses, and aquatic plants, and broad-leaved plants that are not woody. Some PVs are commonly grown as annuals (e.g., African eggplant, Solanum aethiopicum) or have both annual and perennial forms (e.g., Ethiopian kale, Brassica carinata). To fit our definition, PVs must provide multiple years of harvest, unlike some perennial plants that are used as vegetables but are killed by harvest (e.g., the harvest of palm hearts from single-stemmed palms).

As the name suggests, PVs are eaten as vegetables. Edible vegetative parts include shoots, leaves, cactus pads, and stems. Culinary herbs, which are only consumed in small quantities, are not considered PVs, although usage varies between cultures and regions so that a culinary herb in one place may be used as a vegetable in another. 1 Flowers, flower buds, and flower stalks (inflorescences) are also considered perennial vegetables. The classification of fruits is more complex, as there is no botanical distinction between vegetable fruits and dessert fruits. For example, a tomato is a fruit used as a vegetable. For our purposes, if a fruit is sweet and/or sour and mostly eaten out of hand or as a dessert, it is not considered a PV. However, if it is used in a salad, cooked in a stew, or otherwise served as part of a meal, we consider it a PV. In some cases, a fruit is a vegetable when unripe, and a dessert fruit when ripe; this is the case for papayas and mangos. Finally, the unripe seeds of many plants are used as vegetables, even if those seeds become dry staple crops when mature (like pigeon peas, which can be eaten as a vegetable when green and as a pulse when dried). Root crops and starchy fruits like bananas are excluded from our definition of perennial vegetables; they are more properly considered staple crops because they are grown for starch rather than vitamins. Root crops are also not properly perennial, as they must be dug from the soil to harvest the edible portion. Table 1 lists edible plant parts that are harvested from three different types of perennial plants (with annual crops also listed for reference).

| Table 1. Edible plant parts, with examples given for annuals and for three types of perennial vegetable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parts Used | Annual(for reference) | Perennial Herb | Perennial Vine | Woody Perennial |

| Leaves, shoots, and stems | spinach (Spinacia oleracea), lettuce (Lactuca sativa), cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) | belembe (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) | Malabar spinach (Basella alba) | chaya (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius) |

| Flower, flowerbuds | broccoli (Brassica oleracea var. Italica), squash blossom (Cucurbita pepo flowers) | globe artichoke (Cynara scolymus) | loroco (Fernaldia pandurata) | agati (Sesbania grandiflora) |

| Fruits used as vegetables | tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) eggplant (Solanum melongena), pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo) | African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum) | chayote (Sechium edule) | moringa (Moringa oleifera) |

| Unripe seeds | pea (Pisum sativum), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata), sweet corn (Zea mays convar. saccharata var. rugosa) | (no species in this category) | lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus) | perennial pigeon pea (Cajanus cajan) |

Nutrient Deficiencies

Nutrient deficiencies that cause health problems result from inadequate intake of vitamins, minerals, and other nutrients. Traditional malnutrition affects some two billion people, largely in the regions in which EDN readers live and/or work. Traditional malnutrition involves deficiencies in iron, zinc, Vitamin A, folate, and iodine (iodine is not found in large quantities in plants but is abundant in many seaweeds). Low levels of these nutrients in the diet can cause anemia, birth defects, and blindness in children. Deficiencies can also slow growth in children and impair immune systems.

By contrast, we can identify a second set of deficiencies, this one associated with the industrialized diet. Industrial diet deficiencies are a problem in countries like the United States, but also, increasingly, in the urban centers of the tropics. Industrial diets are often deficient in fiber, calcium, magnesium, and Vitamins A, C and E. Diseases that result from these deficiencies include diabetes, obesity, high blood pressure, heart disease, and osteoporosis.

One thing both sets of deficiencies have in common is a lack of fruits and vegetables in the diet. PVs can help address both.

Diversity of Perennial Vegetables

PV species are highly diverse and far more abundant than many people realize. Our study evaluated 613 cultivated PV species, representing seven percent of all cultivated crop species, and a third to half of all vegetable species.

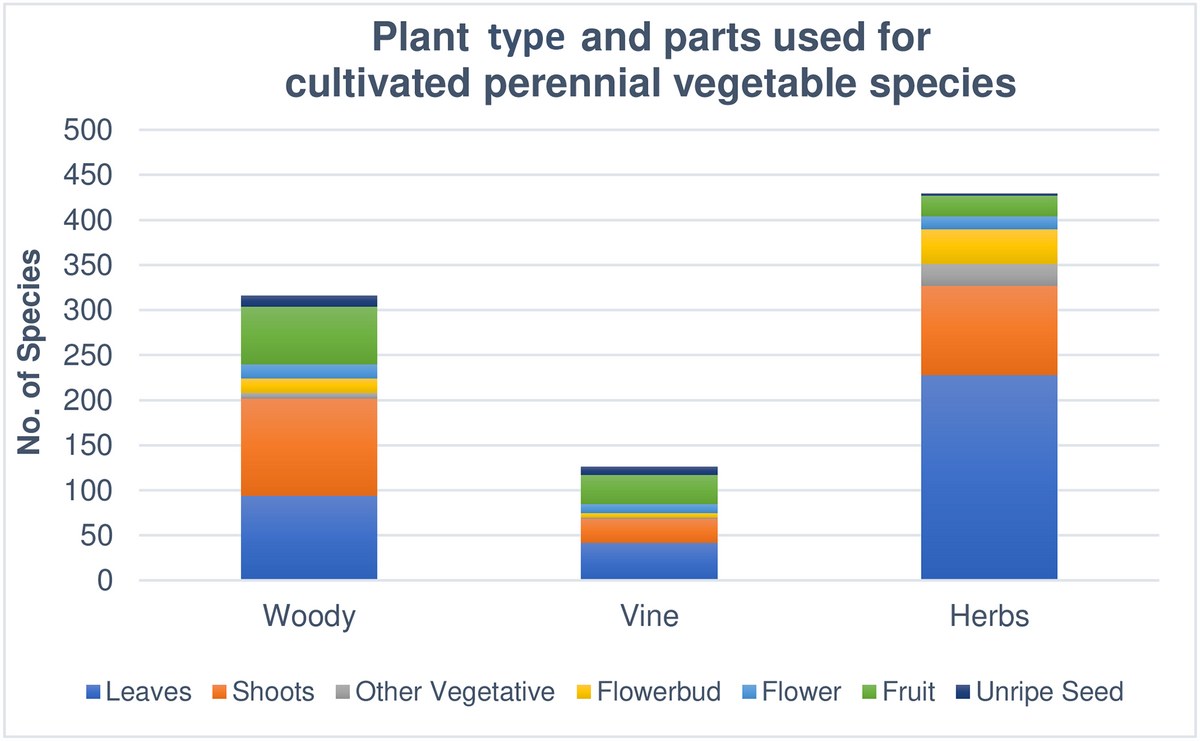

Just over a third of cultivated PVs are woody plants, while half are herbaceous. The remainder are vines. Leaves are most commonly consumed, followed by shoots and then fruits. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Plant type and parts used for cultivated perennial vegetable species. Source: Eric Toensmeier

PVs are largely undomesticated. 61% are regional crops that are grown in gardens and farms in their native range, but have not spread elsewhere. They represent a powerful but neglected tool for improved nutrition. Chaya and moringa were in this category decades ago, but they are now grown around the tropics. Another 31% of PVs are minor global crops, grown at a modest scale outside of their region of origin. Only 3% are major commercial foods at the global level (including olive, avocado, and globe artichoke; a number of other commercially-grown PVs, like okra and leeks, are usually grown as annuals).2

Perennial Vegetable Nutrition

We used data from a set of reference vegetables and nutrition information from PVs to compare the levels of key nutrients needed to address nutrient deficiencies. For the reference vegetables, we chose common species that are marketed globally, with data tracked by the FAO. These include 22 commonly grown and widely marketed crops, including the annual reference species listed in Table 1.

In order to rank the nutrient levels of PVs, we set nutrient level categories based on those used for the reference vegetables (Table 2). Nutrient levels below the lowest amounts found in the reference vegetables are “very low.” Within the range of the reference vegetables, the lowest third are “low,” the middle third are “medium,” and the upper third are “high.” Crops with nutrient levels higher than the reference vegetables are “very high,” and nutrient levels twice as high as the highest reference crop nutrient are “extremely high.”

| Table 2. Nutrient concentration categories based on reference crop nutrient levels (All values refer to amounts per 100 g fresh plant weight). | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber | Ca | Fe | Mg | Zn | Vitamin A | Vitamin B9 | Vitamin C | Vitamin E | |

| % | mg/100g | mg/100g | mg/100g | mg/100g | Mg Retinol Activity Equivalent | mg/100g | mg/100g | mg/100g | |

| Very low (VL) | 0.00-0.39 | 0.00-11.84 | 0.00- 0.46 | 0.00-11.24 | 0.00- 0.15 | 0.00 | 0.00-13.49 | 0.00- 5.64 | 0.00- 0.04 |

| Low (L) | 0.40-1.45 | 11.85-86.71 | 0.47- 1.01 | 11.25-35.75 | 0.16- 0.29 | 0.00- 0.18 | 13.50-73.07 | 5.65-42.33 | 0.05- 0.73 |

| Medium (M) | 1.46-2.50 | 86.72-161.57 | 1.02- 1.55 | 35.76-60.26 | 0.30- 0.42 | 0.19- 0.37 | 73.08-132.63 | 42.34-79.01 | 0.74- 1.42 |

| High (H) | 2.51-3.85 | 161.58-238.70 | 1.56- 2.11 | 60.27-85.50 | 0.43- 0.56 | 0.38- 0.55 | 132.64-194.00 | 79.02-116.80 | 1.43- 2.54 |

| Very high (VH) | 3.86-7.15 | 238.71-477.40 | 2.12- 4.21 | 85.51-171.00 | 0.57- 1.12 | 0.56- 1.11 | 194.01-388.00 | 116.81-233.59 | 2.55- 5.08 |

| Extremely high (XH) | 7.16+ | 477.41+ | 4.22+ | 171.01+ | 1.13+ | 1.12+ | 388.01+ | 233.6+ | 5.09 |

| See text of article (directly above this table) for a description of how we determined categories | |||||||||

We were pleased to learn that PVs have excellent potential to address nutrient deficiencies. An impressive 154 of the 240 PVs for which we had nutrient data were superabundant (“very high” or “extremely high”) in at least one nutrient, and frequently in more than one. In fact, 23 species (10% of PVs for which we found data) were superabundant in four or more key nutrients needed to address deficiencies! We were especially interested to note that trees with edible leaves were superabundant in more nutrients than any other type of PV.

For our study, we also determined the species with the highest levels of nutrients needed to address each of our two categories of nutrient deficiencies. We tallied a score for each species, giving three points for each nutrient that ranked “extremely high,” two points for “very high,” and one point for “high.” If the combined score for a species totaled six or more, it was given a “multinutrient” ranking. Table 3 lists multinutrient species to address traditional malnutrition, and Table 4 lists multinutrient species to address industrial diet deficiencies. Both tables indicate, for each PV, which nutrients occur at high, very high, or extremely high levels.

| Table 3. Multinutrient species to address traditional malnutrition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type of Perennial | Thermal ClimateZ | Rainfall | Part EatenY | FeX | ZnX | Vitamin AX | FolateX |

| Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (chaya) |

Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid, arid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||

| Malva sylvestris (common mallow) | Perennial herb | Temperate, boreal/artic | Humid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||

| Manihot esculenta (cassava) | Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | XH | XH | VH | |

| Momordica cochinchinensis (gac) | Perennial vine | Tropical | Humid | Leaf, unripe fruit, fruit | VH | VH | VH | H |

| Monochoria vaginalis (pickerel weed)V |

Perennial herb | Tropical | Aquatic | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | |

| Moringa oleifera (moringa) | Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf, unripe fruit, flowerbud | XH | VH | VH | |

| Morus alba (white mulberry)V | Woody | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | XH | XH | VH | |

| Persicaria barbata (knot grass)V | Perennial herb | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | XH | VH | VH | |

| Pterocarpus mildbraedii (padouk blanc [French]) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||

| Salix reticulata (netleaf willow) | Woody | Boreal/artic | Humid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||

| Senna obtusifolia (sicklepod)V | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||

| Senna sophera (kasundi [Hindi])V | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | H |

| Solanum aethiopicum (Ethiopian eggplant) | Perennial herb | TropicalW | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | XH | VH | VH | |

| Toona sinensis (Chinese toon) | Woody | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | XH | XH | XH | |

| Ulmus pumila (Siberian elm)V | Woody | Temperate, boreal/artic | Humid, semi-arid, arid | Fruit | XH | XH | ||

| Vitis vinifera (wine grape) | Perennial vine | Tropical, temperate, boreal/artic | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | |

| Z“Tropical” indicates lowland tropics, highland tropics, and/or subtropics. “Temperate” indicates warm temperate and/or cold temperate. “Boreal/arctic” indicates boreal and/or arctic. YWhere multiple plant parts are listed, the nutrient rank is obtained by combining nutrition information for all the edible parts. XSee Table 2 and surrounding text for a description of the nutrient concentration categories (XH, VH, H). WSuitable for cultivation as an annual throughout temperate zones as well. VSpecies considered as weedy in one or more locations. |

||||||||

| Table 4. Multinutrient species to address industrial diet deficiencies | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type of Perennial | Thermal ClimateZ | Rainfall | Part EatenY | FiberX | CaX | MgX | Vitamin AX | Vitamin CX | Vitamin EX |

| Asclepias syriaca (common milkweed)V | Perennial herb | Temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | VH | XH | |||

| Atriplex halimus (saltbush) | Woody | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | XH | XH | |||

| Bambusa polymorpha (Burmese bamboo) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Shoot | VH | VH | VH | |||

| Cnidoscolus aconitifolius (chaya) |

Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid, arid | Leaf | VH | VH | XH | VH | ||

| Coccinia grandis (ivy gourd)V | Perennial vine | Tropical | Humid | Leaf, unripe fruit | VH | H | XH | |||

| Dicliptera chinensis (Chinese foldwing)V | Perennial herb | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | VH | XH | |||

| Epilobium angustifolium (willow herb)V | Perennial herb | Temperate, boreal/artic | Humid, semi-arid | Shoot | H | H | VH | VH | ||

| Gnetum gnemon (Spanish joint fir) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | H | H | VH | H | |

| Limnocharis flava (yellow velvetleaf)V | Perennial herb | Tropical | Aquatic | Leaf, stem, flowerbud | VH | XH | XH | H | ||

| Manihot esculenta (cassava) | Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | H | VH | VH | VH | XH | |

| Momordica cochinchinensis (gac) | Perennial vine | Tropical | Humid | Leaf, unripe fruit, fruit | H | VH | VH | VH | XH | |

| Moringa oleifera (moringa) | Woody | Tropical | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf, unripe fruit, flowerbud | H | VH | VH | VH | VH | H |

| Morus alba (white mulberry)V | Woody | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | VH | VH | |

| Pisonia umbellifera (umbrella catchbirdtree) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | |||

| Sauropus androgynous (katuk) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | VH | XH | |||

| Senna obtusifolia (sicklepod)V | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | VH | XH | VH | |||

| Senna sophera (kasundi [Hindi])V | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | H | VH | VH | VH | ||

| Sesbania grandiflora (vegetable hummingbird) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | XH | VH | VH | H | H | |

| Silene vulgaris (maiden’s tears) | Perennial herb | Temperate, boreal/arctic | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | VH | XH | |||

| Solanum aethiopicum (Ethiopian eggplant) | Perennial herb | TropicalW | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | VH | VH | XH | ||

| Toona sinensis (Chinese toon) | Woody | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | VH | XH | VH | XH | ||

| Trichanthera gigantea (nacedero) | Woody | Tropical | Humid | Leaf | XH | XH | ||||

| Urtica dioica (stinging nettle)V | Perennial herb | Temperate, boreal/artic | Humid | Leaf | H | VH | H | VH | XH | |

| Vitis vinifera (wine grape) | Perennial vine | Tropical, temperate | Humid, semi-arid | Leaf | XH | VH | VH | VH | H | |

| Z“Tropical” indicates lowland tropics, highland tropics, and/or subtropics. “Temperate” indicates warm temperate and/or cold temperate. “Boreal/arctic” indicates boreal and/or arctic. YWhere multiple plant parts are listed, the nutrient rank is obtained by combining nutrition information for all the edible parts. XSee Table 2 and surrounding text for a description of the nutrient concentration categories (XH, VH, H). WSuitable for cultivation as an annual throughout temperate zones as well. VSpecies considered as weedy in one or more locations. |

||||||||||

A few standout species are ranked as multinutrient for both forms of deficiencies. These nutritional powerhouses are:

- woody plants - chaya, cassava leaf, moringa, white mulberry (varieties with palatable leaves), Senna obtusifolia and S. sophera (both of which are strongly laxative when leaves are mature), and Toona sinensis;

- vines - grape leaves and the perennial cucurbit Momordica cochinchinensis (both vines); and

- perennial herb (often grown as an annual) - African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum).

While this article highlights PVs that rank highly as multinutrient crops, some less-common annuals do as well. Many of these are offered by ECHO. For traditional malnutrition, ECHO offers the multinutrient species Amaranthus cruentus (grain amaranth), Celosia argentea (Lagos spinach), Corchorus olitorius (Jute), Solanum scabrum (African nightshade), and Vigna unguiculata (cowpea). Both Corchorus olitorius and Vigna unguiculata are also multinutrient species for industrial diet deficiencies.

Other Benefits and Drawbacks of Perennial Vegetables

Perennial vegetables offer many advantages to smallholders and gardeners in the tropics. For example, perennial crops sequester carbon and therefore play a role in climate change mitigation. They can also help farmers adapt to climate change, such as when PVs have deep roots that help them resist droughts.

Perennial crops diversify production systems, often offering food when other crops are not available. For example, many trees with edible leaves, when coppiced, will continue to offer vegetables well into the dry season. Also, PVs can sometimes be produced in areas not suited to annual crops. Some perennial vegetables, including aquatic species, can be grown in very wet areas. Others are suited to shade, making them ideal for the understory of agroforestry systems.

Perennial crops also bring some disadvantages. For one thing, they can be difficult to acquire. It may be challenging to adapt PVs to local cooking styles, and some PVs are toxic unless properly processed. Finding markets for unfamiliar crops can be difficult. Many PVs are propagated by cuttings or through other vegetative means, which makes them vulnerable to viruses and some other diseases.

With any new crop, including perennials, potential weediness is a concern. Tables 3 and 4 indicate plants that are considered weeds in various locations. Be very cautious about planting these in new areas—but do plant them where they are native! These plants represent a source of nutrition that is easily overlooked. This concept is described more fully by Rinaudo (2002) in EDN 77 [http://edn.link/qaag7k].

Note that nutrition, flavor, productivity and ease of cultivation are independent of each other. These vegetables will only be nutritious if they can be produced easily and taste good. As ECHO staff members have noted, it is not as easy to eat 100 grams of moringa as it is to eat 100 grams of spinach. Perhaps the best approach, recommended by Dr. Martin Price (ECHO founder), is to “eat like a deer, not like a cow” (i.e. consume modest amounts of a large diversity of vegetables, instead of large amounts of one single species).

Conclusion

The world’s farmers and gardeners who selected these species and brought them into cultivation deserve our heartfelt thanks. The hundreds of cultivated species of PVs are here when they are needed, to address deficiencies that impact billions of people, to turn unproductive parts of farms and gardens into food and income, and to address climate change. We find it especially promising that trees with edible leaves are the most nutritious category and contain some of the world’s most nutritious vegetables, as these species have a desirable climate impact and are relatively easy to grow.

These valuable PV crops should be promoted. Efforts should begin with species native to a region, both to minimize potential invasiveness and to work with species that are more familiar to people in the community. With over 600 species to choose from, hailing from all over the world, there is a PV for almost anywhere that people grow food. The paper upon which this article was based is available online; it includes links to the full data set, which can be used to identify suitable species for any given region. It also includes nutrient data on annual crops for which data were available.

Though the data in the online article are extensive, they are incomplete. Only for a few species of PV were we able to find all of the nutrients we were looking for; many important species had no data at all.

ECHO has been offering many of these species for decades, and our team was very pleased to be able to offer additional research to back up this important work.

Resources

The full article is available online for free download at http://edn.link/tones

ECHO’s Seed Bank is a source of seeds and cuttings for many of the PVs highlighted in this article.

Cite as:

Toensmeier, E. 2021. Perennial Vegetables and Nutrition. ECHO Development Notes no. 150.