Over the past 30 plus years that we have been working with small-scale farmers in Central Africa, we have enjoyed the wonderful lushness of its forests, savannahs, and rivers. In addition, we have been privileged to get to know some of the many people groups, with their different cultures and languages, of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), the Central African Republic (CAR), and Cameroon.

But, despite the appearance of a tropical paradise, life in Central Africa is harsh. Most Central Africans are dependent on their own fields and gardens for survival. Though they are very good farmers and work hard to make ends meet, farming for survival has always been a difficult and time-consuming task. Any change in their farming method that requires extra finances or time is virtually impossible.

Regardless of the fact that food security is the main preoccupation of nearly all Central Africans, they are not quite able to achieve it. Malnutrition and poor health are therefore an inevitable result. A study by Doctors Without Borders, at our hospital in Gamboula, CAR, confirmed this situation. Results showed that 8%-12% of children under the age of five in this area are severely malnourished. This crisis situation deserves the attention of the local as well as the international community. By working together, appropriate solutions to the problem can be found. The introduction of new crops provides potential to facilitate such solutions.

THE IMPORTANCE OF FRUITS AND NUTS

To alleviate existing hunger and malnutrition problems, a number of strategies are being tried here in CAR. Some are promising, but most have not yet produced the desired results.

However, the cultivation of fruit trees is one strategy that we feel can fight hunger on a long-term, sustainable basis. Though the importance of raising fruit trees has been underestimated by development communities, it ought to be a major element in any development scheme.

Fruits and nuts, when eaten in the right amounts and combinations, are capable of providing all the necessary nutrition that the body needs, including protein, carbohydrates, fats, vitamins, minerals, oils, and sugars. They also provide great enjoyment from the variety of tastes and sweetness that other crops don’t provide. With proper selection of fruit tree species, you can have different kinds of fruit all year round. Once fruit trees are established, very little labor is required to maintain them and they continue to produce for many years. They will produce food even during difficult times when other garden produce may be hard to obtain. Fruit trees can also provide other benefits that include lumber, poles, medicine, income, shade, firewood, ornamental value, soil improvement, reforestation and protection of the environment

INTRODUCING FRUIT TREES—OUR EARLY EXPERIENCE IN THE DRC

We remember how difficult it was, during our early days in Congo, for the local people to see the importance of planting fruit trees, even though they appreciated eating the fruit.

There were taboos against planting fruit trees. One excuse for not planting trees was the discouraging fact that many fruit trees take 7-10 years before they start to produce. Another thing we noticed was that there were very few young trees. Most existing trees had been planted during the colonial era, meaning they were already old trees. The few young ones were most likely “accidental” plantings, where the seed was tossed into a compost pile and left to germinate and grow on its own. As we walked around villages, we could see basically five common fruit trees around houses and along the road—mangos, bananas, papayas, pineapples, and oil palm. Occasionally, we saw other trees such as citrus, coconuts, ambarella, soursop, guava and breadfruit. But for the most part, fruit trees were lacking in number and variety, and many had only short fruiting seasons.

We took a couple of different surveys and found that the diet of the local people was low in protein and essential vitamins and minerals, but high in carbohydrates. So it made sense to us to introduce beans, fish and fruit as important additions to the diet

We spent 20 years in northwestern DRC introducing fruit trees, bean gardening, and fish farming. We observed a radical transformation in the consumption of these items, which positively affected nearly every household in that region. Due to civil war we had to leave, but 10 years later we were able to visit the area. We were astounded at the sheer number of new fruit trees that had been accepted by the people and that had spread even to remote areas where we had not worked. In one village, we counted more than 500 jackfruit trees that had replaced the mango as the most popular fruit tree.

We initially had done trials and selected several bean varieties at our agriculture center gardens, and followed these by seminars and trials with interested villagers. They selected the cowpea (or black-eyed pea) as their favorite because it was easy to grow, high yielding, matures in two months, is easy to prepare for eating, and is, of course, tasty. The cowpea has since become a widespread cash crop, in addition to being a highly nutritious major addition to the diet.

When introducing fruit trees, the same criteria apply. In order for a tree program to be successful, the methods must be easy and the results quick. In our case, there was no question that the people enjoyed eating fruit—the question was whether or not they really would take the time and energy to plant and raise fruit trees. At first, only a few people wanted to try raising fruit, so we included the growing of fruit trees in our village seminars. For those that attended seminars and were interested, we were able to help out with a few trees from our small nursery. As we worked more and more with tropical fruit trees, we selected varieties that were good tasting, high yielding, and produced in two years or less. We chose jackfruit, bunchosia, canistel, and rollinia. After early successes with these few villagers, more and more people began to see the importance and simplicity of raising fruit trees. They started planting their own trees spontaneously.

So how does one go about introducing new fruit tree species, or promoting fruit trees as a legitimate food source?

THE VILLAGE SURVEY

A good starting point, especially in an area stricken with malnutrition, is to meet with the people and see what kinds of foods they raise in their own gardens. Do some kind of survey, whether a formal questionnaire or a verbal one with note taking, but also visit gardens and observe what people are growing and in what quantities. Sit down and enjoy a meal with people, as a way to actually see their priorities in food raising. But be aware of the possibility of getting a false impression if people have put on the best for their guest. Asking questions is still very important.

Sources of protein are sometimes underestimated by western development workers, because people usually don’t volunteer information about things that are not asked. Because of this, be sure to ask people about such things as insects, caterpillars, little fish and snails. Most likely you will find that quite a variety of food types are grown and collected, but that 95% of carbohydrates come from one source. (That source is cassava here in western CAR.) Getting information from hospitals and other sources can add to the overall nutrition picture.

Find out the seasonal availability of foods. During certain times of the year, many garden foods become scarce. This is when fruit and nut trees could fill in the food gap. For example, the children of northern CAR eat an incredible quantity of mangos during the months of April to June, when garden produce is at its lowest. Those mangos just may be the difference between getting by and developing severe malnutrition. Mangos are an important part of the seasonal diet. Such information would probably not be discovered by a typical survey. An observer would have to notice the many mango trees and then ask if people eat mangos, and at what time of year.

As an important part of any village survey, inventory the fruit trees and their seasonal availability. Once the information is compiled, you can get a picture of the availability of all the foods that belong to the basic three food groups: protein; minerals and vitamins; and carbohydrates and fats. Then a search can be made for the proper fruit tree species to help with nutritional weaknesses and seasonal scarcities.

KNOWING WHAT FRUIT TREES TO PLANT

It can be difficult to decide which fruit trees to plant, but every tree has its own unique qualities. We have written a book about 100 species of fruiting trees, vines and shrubs that are among the most likely candidates for a Central African home garden. This book, entitled The Top 100 Fruits, Nuts, and Spices for the Central African Home Garden should be available from the ECHO bookstore when published. The information is valid for any tropical region of the world.

Most fruit books sold in Florida or California deal with cold hardiness as a significant issue, but do not tell much about requirements of rainfall, altitude, soil type, humidity, planting distances, uses, and other bits of information that you should really know about a tree before trying to grow it. Our book addresses the ideal and extreme growing conditions of the various plants according to our own experience and observations, plus some information provided by others growing these plants in different areas. This kind of information can help you choose which species seem best for your particular region.

For instance, if you are looking for an all-around great fruit tree that has become very popular with many Central Africans, plant a jackfruit. This India native has sweet tasty flesh and an edible nut, so it fits into all three of the nutrition food groups: protein; vitamins and minerals; and carbohydrates and fats.

Jackfruit happens to be the largest of the tropical fruits; we’ve raised some over 25 kg (55 lb). One fruit can supply nutritious food to a family, and also to the neighbors watching nearby! Even more amazing, this tree has been known to begin fruit production only 2 years after planting a seed. It is very robust and grows in almost any soil and in a fairly wide climatic zone as well.

In order to help end hunger quickly, the jackfruit tree should be included in a farmer’s planting if possible. Not all jackfruit trees are exactly alike, especially when grown from seed. Some produce poor-tasting fruit, or soft, slippery pulp; others are hard to open or have excessive amounts of sticky sap. Only seed from fast-producing trees with good-tasting fruit should be planted.

The most important caution is to be sure you do not plant a variety that takes 10 years to produce. Trees that produce in 2 or 3 years but turn out to be poor can be replaced without wasting too much time. Finding you have a bad jackfruit after 10 years is just plain discouraging and should never happen when fast-fruiting varieties are available.

The fruiting period of the tree is another important consideration when selecting a fruit species. The jackfruit has a very long fruiting season, producing most of the year. If you have several jackfruit trees, you will most likely harvest some ripe fruit every month of the year. So the jackfruit meets all the criteria mentioned earlier. It is fast-growing, simple to grow, has a long season, and is very productive. We share this kind of information in our book, so that a development worker or farmer can have a good idea what to expect from the species listed.

Many trees species have only one short season that lasts 1 or 2 months of the year. They may have delicious fruit and be very nutritious, but they should be planted as compliments to the fast-growing, highly productive species that really encourage people with early success. Little by little, slower growing trees can be introduced while people enjoy the production of the fast trees. If your goal is to provide all the daily nutrients a person needs all year, then you will need to work out a continual fruiting season by incorporating many different kinds of trees and vines. That way, with the combination of different plants, one garden can produce fruit at all times of the year. This is the idea behind an agroforestry “tree garden,” a garden that supplies food and other daily needs to a family year after year. You can still plant and live off of annual crops, but a permanent food-supplying tree garden has tremendous long-term benefits.

PLANT RESEARCH AND TRAINING CENTER

A plant research and training center can be appropriate in order to better study fruit trees and other crops (both indigenous and imported), and to learn how to improve them. At these centers, new varieties are tested next to indigenous ones to see how well they adapt to the local environment and farming systems. Many times, new varieties do not fare well and fail the test. When that happens, the center itself takes the loss before it reaches the farmer. If farmers were to try all the new plants and methods that development people and projects introduce, without first trying them in an experimental center, many farmers would starve. But this way, the research center will make the mistakes and the farmers will take the successes. Farmers can learn from the center in practical hands-on ways, and can also be taught in seminars at the center or in nearby villages.

To establish a center, all you need is some land to work with and perhaps a building of sorts to serve as an office and to store tools, seeds, nursery sacks, and other supplies. For a really small project, someone’s house can be used. At the center, you can research the growth habits and water needs of trees. You can try new pruning methods that could improve production. Then you can instruct farmers in ways to modify and improve their known practices. [Ed: For further reading on these types of centers, visit ECHO’s website to access a Technical Note entitled, “Small Farm Resource and Development Project.”]

WHERE TO SEARCH FOR FRUIT TREES TO PLANT

When looking for seeds or trees to plant in your tree garden, look locally first. You may be surprised at the varieties of fruit trees around homes and in towns near you. We have found exceptional fruit tree varieties in schoolyards, churchyards, residences, along roadsides and in abandoned lots. It does not hurt to ask around where the best-tasting fruit trees are. Of course, if there happens to be a local nursery with fruit trees, you will have a source of trees to choose from and the owner will probably be very knowledgeable about his plants.

Most of the time, we have hand-collected seed or seedlings from under trees in places we have visited—mission stations, government posts, research stations and individual homes. While we were getting started in Congo, we did all this and even traveled around the world looking for species with good potential for our region. We then brought back seeds for trials in our agricultural center. As a result, today a number of good fruit tree species are widespread in Northern Congo and CAR.

Most people don’t have opportunity to travel widely looking for new fruit tree species, but with the internet so common in the world today, information about amazing new fruit species or varieties—that any fruit enthusiast would want to plant—is easily accessible. Many tropical plant outfits on the web accept orders online and can ship overseas, but be aware that it is getting more difficult to send plant material between countries.

SHIPPING SEEDS AND SEEDLINGS OVERSEAS

Transporting plants and seeds long distances can be a difficult task, but if you follow the instructions below, you can maximize your success rate when introducing new or improved species. Below are tips on transporting seeds and live plants.

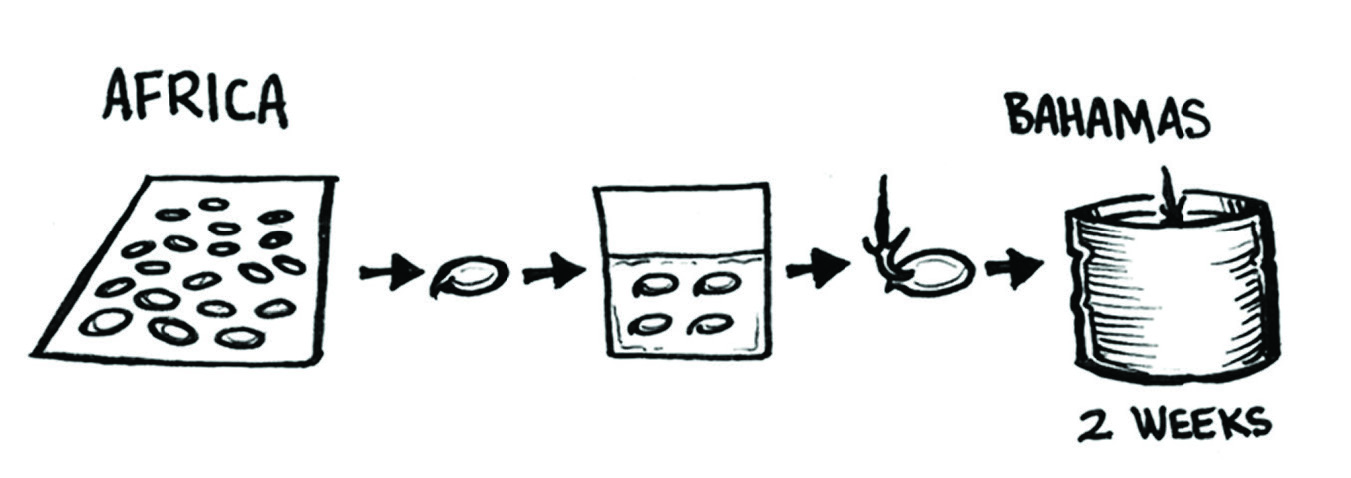

Seeds

The degree of difficulty in transporting tree seeds varies with species. Some, like the annonas and guava (Psidium guajava), have hard seed coats and only require that you clean them of all their flesh and dry them in the shade. These kinds of seeds can be bagged dry and without any medium (sawdust, potting mix).

Fragile tree seeds, like safu (Dacryodes edulis) and rambutan (Nephelium lappaceum) are much more difficult. They must be cleaned and placed immediately in some sort of sterile medium that is neither too dry nor too damp in order to initiate a slow germination. They can also be sent clean and nearly dry in Ziploc® bags with most of the air pushed out, with no medium at all. We have had jackfruit seeds survive nine months using this second method.

For seeds that are perishable, extra sensitive, tender or have short-term viability, the container that encloses them should be humid inside, but not wet. Placing fragile seeds in a humid medium is like planting them, and they begin germinating during transport so that when they get to their destination, they may be young seedlings, complete with roots and shoots.

Though not ideal to have seeds sprouting roots and shoots during transit, it is better than having them rot. If the humidity is a bit lower they will be much less developed—or will have no root or shoot growth at all—but will still be in good condition. Sending the seeds in a dry medium will kill them.

Adding a little bit of powdered fungicide is helpful to reduce the likelihood of rot. Some countries have restrictions on using fungicides, so please be careful. If there is any flesh on the seeds, or if they are too wet, they will be a rotten mass of dead tissue when they arrive. We have received numerous seed shipments in that sad condition. On the other hand, we once received a shipment of rambutan, durian, and marang seeds that were packed correctly and survived three months in the postal system! They came from Borneo all the way to Central Africa and had all sprouted into a tangled ball, but we separated the seedlings and planted them with no problem. Still, whenever possible, we recommend having someone hand-carry seeds in their luggage to ensure proper care and speed in getting them to their destination

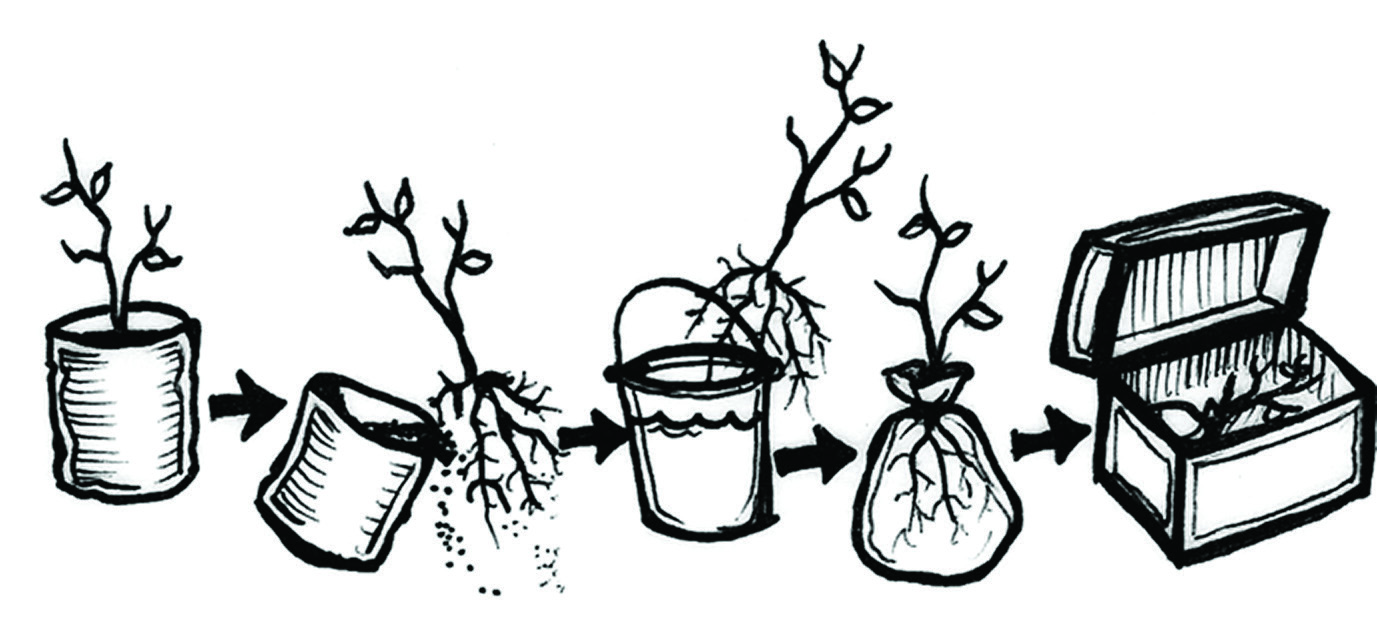

- Obtain necessary documentation. When crossing international borders, trees should be inspected by a government plant inspector prior to travel. You do NOT want to transport any plant diseases or insects that could potentially ruin local crops. Therefore, a phytosanitary certificate from the country of origin should be obtained; this document allows for legal transport of the trees into a foreign country. Trees are often inspected at the destination airport. Sometimes a certificate of origin and/or plant import permit (from the country the plants are being sent to) is required

- Procure supplies. Supplies to be secured ahead of time include plastic bags of different sizes, twist ties or string, pruners, buckets, and a plastic trunk to pack down the trees. All the trees should be put in one location where there is access to water (e.g., a garden hose, well, or stream) and a place to leave the left-over soil.

- Pack the trees. Next comes the bare-rooting process for shipping or transporting trees overseas or any long distance

A minimum of two days before shipping, measure and trim the trees to the length of the trunk in which they will be shipped. Also prune the leaves at this time to allow the cuts to seal and the plant to recover before the next step. Do not remove all the leaves from the plants. Typically we prune off about half of each leaf. Pruning helps to reduce transpiration and cuts down on leaf rot. Leaving half of each leaf promotes faster recovery at the final destination.

Remove the tree from its pot and begin to massage the soil to loosen it from the roots. We try to get as much soil separated from the roots as possible in this step.

Then put clean water in a bucket and dip the roots in the water several times, working all the soil off the roots with your fingers. At the end of the root bath, all the soil should be gone and the roots should be clean. Trim back extralong roots with a pruner.

After the roots have been washed and excess water shaken off, slip a bag over the roots and tie it to the base of the tree. Only the roots are bagged—not the upper part of the tree.

Carefully lay the prepared plants in the bottom of the trunk or suitcase. They can be stacked on top of each other but should not be crammed too tightly. The largest plants should go in first.

- Ensure survival of the trees upon reaching destination. When the plants have cleared customs, we have often found ourselves stuck in some capital city for a few days/nights because of shopping needs or personal paper work that needs to be attended to. As a result, the trees end up in their transport mode for longer than is really good for them. If this happens to you, open the trunk and stand the trees up to allow them to air out a bit (condensation will have collected in the container). Do not expose the trees to any direct sunlight during this time, and keep them in as cool a place as possible—but not an air conditioned room, which will be too dry. The low light exposure will be just enough for the plants to stay alive without drying out too much. When you are ready to continue the trip, pack the trees down once again.

When you reach the final destination, immediately plant the trees into nursery sacks filled with well-composted soil. Make arrangements of some kind in advance so that this will be possible. Fatal root damage can occur if the planting material is dry at the time of planting, so water the trees well as soon as they are potted into the moist soil or compost medium. Then keep them in at least 50% shade for 3-4 weeks, allowing them to recover before exposing them to more sunlight. We generally wait at least a couple of months before attempting to plant new arrivals of this kind out in a field. Some plants may take 6 months to a year before they are ready to be planted out.

We have transported many hundreds of trees to Africa in this way, and have had a 75% success rate overall. Your success rate will depend on the length of trip and what kinds of plants you are transporting. Quite often, young grafted fruit trees and marcots are the most sensitive and can have quite a high death rate. Sometimes the graft of a grafted tree will die while the root stock survives. It usually takes us 5-7 days from bare-rooting to planting in nursery sacks, and it is amazing that the trees recover as well as they do!

THE NURSERY

For successful introduction of new plant or tree species, you will need a place to germinate and care for the young seedlings. In other words, you need a nursery where seeds and seedlings are placed in germination beds or sacks, then cared for until they are ready to plant in the field. The nursery is also where the trees get acclimated to the local weather. Requirements for a nursery include a close water source, available compost, some shade, and protection from animals or people. Protection from animals is an absolute must. Either fence the nursery well or locate it far from animals. Otherwise, local livestock will destroy any edible plant in the nursery—not an economical way to feed animals!

Once the seedlings have grown enough to transplant into some kind of container, plastic nursery sacks are ideal. If they are not available or affordable, planting containers can be made from plastic bottles, plastic storage bags, folded banana leaves, rattan baskets, split bamboo sections tied together with a rubber band, old cans and gourds. Visit the nursery every day, to ensure that the young trees have sufficient water, weeds are removed, and pests are not bothering the plants.

THE FINAL GROWING SITE

When the roots of trees start to emerge from the bottom of nursery sacks, they need to be planted out in the field. If the trees have been in the shade in the nursery, move them to a sunnier location to get used to full sun. This normally takes 2-3 weeks. Each region has its seasons, and the best time to plant out new trees is at the beginning of the rainy season. The timing of nursery stock preparation is crucial to success with fruit tree introductions. If seedlings are not ready to be planted out when the season is right, you will have to hold them over until the next year

.If you want to plant a whole orchard, be sure to prepare the fields for the new trees. Very few people in Central Africa are able to water an orchard of trees during the dry season, so you will need to get the trees in place to take advantage of the whole growing season. Otherwise the next dry season will damage or kill many of the new trees.

Many people just want to plant one or two trees next to their homes. These people don’t need to do extensive preparation. They may be able to plant a tree (or two) at almost any time of year, if they are able to water and care for it. Village home trees should be individually fenced and mulched with compost for best results.

In our rural setting we have found a tree garden to be very useful. If the most robust and fast-growing species are planted out at the right time of year, the results are normally so encouraging that people really get excited about planting trees and will be asking for other species as well. The trees provide enjoyment and good food for many years to come. They may also provide some extra income from fruit sales. Seeing this kind of transformation among a group of people makes it well worth the effort of introducing and promoting new fruit tree species.

CONSIDERING COSTS by ECHO staff

Costs associated with introducing a new fruit crop will obviously vary depending the area in which you work. Here are some things to consider, though.

Ordering material online involves product cost and shipping. There is a definite advantage and drawback when ordering online. You have the opportunity to order a host of seeds and plants that would otherwise be impossible to find in your area. Comparative shopping also allows for garnering great deals. Some major downfalls to online shopping would be: the inability to choose specific plant material (i.e., you can’t inspect the individual plant material before purchasing, so you may receive inferior products); importation may require extra documentation; non-native varieties may not be suited to your climatic conditions, so research is important.

Searching locally should be relatively cost-effective. Local plant material is usually representative of what can be successfully grown in your area as well as revealing some information about market demands for any product you would wish to sell from the plant. Again, costs should be minimal with this method.

When you are the one to ship seeds and plant material, there are material and shipping costs associated. Fragile seeds require the use of a sterile medium (which could be as simple as a plastic bag). The article also mentioned the use a powdered fungicide. Availability and effectiveness of these materials is variable, depending on the seeds in question and, again, your area.

When shipping plant material (as well as seeds), proper documentation and permissions is necessary. This may require some cost and definite research. Materials mentioned in the article that are needed to prepare and ship plant material include:plastic bags (of varying sizes), twist ties or string, pruners, buckets and a plastic trunk. On the receiving end (the final destination of the plants), nursery sacks (or other appropriate container) and well-composted soil are a must to acclimate the plants before planting in the field.

If you are considering a nursery, you must plan for: a dependable water source, quality compost, shade (natural or manmade), protection from animals and theft (e.g., a fence) and plastic nursery sacks for planting. These costs are highly variable because their sources are highly variable. For instance, the water source could be a nearby creek or plumbing. The former would be relatively free, the latter would cost more. Also, shade could be provided by trees that already exist on the property, or shade cloth. Again, the former option is free, the latter requires a purchase.

Gain from introducing a new fruit crop has tremendous potential. On the forefront, as the article mentions, would be increased nutrition. It is difficult to assume the costs of improving quality of life. Secondly, introducing a new fruit crop could serve as supplementation to a family’s diet. This has the potential to decrease costs from purchasing fruit from the market. The final implication of introducing a new fruit crop would be purely economic—income generation. You can garner income from meeting the demands of the market or introducing a new demand with a new fruit. Again, with this, the costs, and definitely the gains, are highly variable.

REFERENCES

Noren, P. and R. Danforth. Agroforestry in the Central African Home Garden–Manual for tree gardening in the humid tropics.

Noren, P and R. Danforth. 100 Tropical Fruits, Nuts, and Spices for the Central African Home Garden.

Lost Crops of Africa, Vol. III, Fruits. 2008. National research Council, Washington, DC. The National Academies Press. 354 pp.

Cite this article as:

Danforth, R. and P. Noren 2011. Introducing a New Fruit Crop. ECHO Technical Note no. 68.