Farmers growing fruit and fruit-bearing vegetables are often faced with the challenge of selling or eating produce before it spoils. Extending the time over which fruit can be eaten or sold after they are harvested is a complex topic. In later issues of ECHO Development Notes we will touch on appropriate options for reducing spoilage while storing and transporting fruit. In this article, however, we focus on the importance of harvesting at the right time. We will start by explaining underlying concepts of fruit development and ripening behavior that influence the timing of fruit harvest. We will then discuss ways to help you decide when to harvest tomatoes and a few commonly-grown tropical fruit.

Foundational concepts

Fruit development

As a fruit ages, it grows, matures, ripens, and senesces (degrades) (Thakur and Sharma, 2019). Fruit grow and mature while attached to the plant. Fruit maturity is reached when, even after removal from the plant or tree, further development can continue normally. Thus, a fruit can be mature but not necessarily ripe. A ripe fruit has attained qualities, like color and texture, that makes it ready to eat. Senescence is the stage in which fruit start to degrade and eventually die.

Ripening behavior

Fruit are categorized as climacteric or non-climacteric based on how they respire, produce ethylene, and respond to ethylene. Respiration uses oxygen and releases carbon dioxide in supplying fruit with the energy, sugars, and pigments (molecules that affect fruit color) required for ripening. Ethylene is a gaseous plant hormone that helps fruit ripen. Climacteric fruit have a period of rapid respiration and ethylene production during ripening. Peak respiration in such fruit is called the respiratory climacteric and generally coincides with the stage of optimal ripeness for eating. Non-climacteric fruit do not have a distinct burst in respiration and ethylene production during ripening.

All fruit respire and produce ethylene at varying rates. Fruit with high respiration rates tend to ripen faster and be more perishable than fruit that respire more slowly. For example, papaya (Carica papaya) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit respire more slowly than avocado (Persea americana) and cherimoya (Annona cherimola) fruit (Kader, 2002).

From a practical standpoint, how fruit ripen influences when they can be picked for maximum shelf life or eating quality. Climacteric fruit will keep ripening after harvest, as long as they were harvested mature. Non-climacteric fruit, on the other hand, will not ripen normally after removal from the plant. Table 1 lists examples of fruit under each category.

| Climacteric fruit | Non-climacteric fruit |

|---|---|

| Avocado (Persea americana) | Coconut (Cocos nucifera) |

| Banana (Musa spp.) | Cucumber (Cucumus sativus) |

| Cherimoya (Annona cherimola) | Eggplant (Solanum melongena) |

| Guava (Psidium guajava) | Litchi (Litchi chinensis) |

| Mango (Mangifera indica) | Orange (Citrus x sinensis) |

| Papaya (Carica papaya) | Starfruit (Averrhoa carambola) |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) | Pineapple (Ananas comosus) |

Timing of harvest matters

Concept

Timing of fruit harvest influences subsequent fruit quality. Fruit harvested too soon will not reach optimal flavor. Overripe fruit become soft and lose flavor soon after harvest.

Fruit generally taste best when ripened on the plant or tree. Non-climacteric fruit should be allowed to fully ripen on the plant for optimal flavor. Climacteric fruit can be ripened either on or off the plant. As long as climacteric fruit are mature at harvest, they will continue to ripen off the plant. Harvesting mature, unripe fruit is done to reduce spoilage of fruit that have to be transported long distances.

Practice

Learn to recognize maturity stages of the fruit you are growing. Maturity tests can be categorized as destructive or nondestructive. Destructive tests are those that damage or destroy the fruit being tested. An example of a destructive test is flesh color, because one must cut into the fruit to determine the color of the flesh inside. Visual indicators like fruit size, shape, and skin color are nondestructive. You do not have to destroy a tomato to see a change from green to red. No single test works well for every fruit-bearing species. For the crop(s) you are working with, find out which tests are most reliable for determining fruit maturity. Of those, select one or two that you can implement in your context. Maturity indicators are given for a few fruit species in the next section, emphasizing those that do not require expensive laboratory equipment. Morton (1987) in, Fruits of Warm Climates [http://edn.link/fwc], also discusses timing of harvest for many tropical and sub-tropical fruit.

Once you know and can identify the maturity stages of the fruit you are dealing with, as well as the optimal stage of ripeness for eating, you can optimize harvest time based on fruit type (climacteric versus non-climacteric) and time until consumption or sale. Farmers growing produce for distant markets will likely want to grow climacteric fruit that can be harvested at a mature green stage before transport.

Guidelines for a few fruit

Avocado

Figure 1. Demonstration of a ’90-degree test.’ Source: Tim Motis

The period or season during which avocado fruit mature varies with variety. This means that farmers can extend the time over which they can sell avocados by simply planting varieties that mature at different times. In table 2 of a University of Florida extension publication, Crane et al. (2020a) shows when various avocado varieties have mature fruit in Florida. For example, the “season of maturity” for ‘Brogden’ is earlier (mid-July to mid-September) than for ‘Choquette’ (end of October to mid-January). As pointed out by Crane et al. (2020a), avocados mature but do not ripen on the tree. They will eventually fall to the ground if left on the tree, but you need to harvest mature fruit for them to ripen well. Mature fruit will ripen within 3 to 8 days. An avocado is mature when it has the right amount of oil in it. If you pick an avocado that doesn’t soften well, and instead becomes shriveled and rubbery, an optimal oil level has not been reached. Signs of maturity include size (large fruit are more likely to be mature) and color (mature fruit tend to become less glossy/shiny), but these signs can vary with variety. Four indicators of avocado maturity are:

whether or not one or two large fruit ripen well after removal from the tree. During the months when your variety of avocado is typically harvested, pick a large fruit and place it on a shelf in your home. Observe the fruit over the next 3 to 8 days, the time it takes for mature fruit to ripen. If the fruit does not reach good eating qualities (e.g., it shrivels or becomes rubbery instead of soft), wait a few days and try again with another large fruit.

- how easily fruit detach from the tree. ECHO staff use a ’90-degree test’ in which fruit are ready to be picked if they easily detach when the peduncle (stalk to which the fruit is attached) is bent at a 90-degree angle (Figure 1).

- dry weight of the flesh. Weigh a sample of flesh from the fruit, and then dry it. The sample should not include parts of the peel or seed. The dry weight is reached when it stops losing weight. Divide the dry weight by the fresh weight and multiply by 100, giving percent dry weight. Dry weight is closely linked to oil content (Lee et al., 1983). It’s time to harvest when the dry weight is close to 20%.

- a simple sound test. If you shake a fruit and hear a rattling sound, the seed has dislodged from the fruit’s flesh and the fruit is ready to be harvested.

Mango

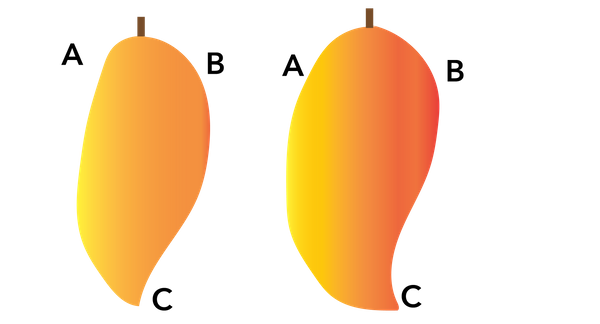

Figure 2. As the mango fruit ripens, observe the rounding and broadening of the shoulders (A and B) and the development of the fruit tip (C). Source: Stacy Swartz

Mangoes will ripen on the tree. To extend the time over which fruit can be stored or transported, however, they are typically picked when firm and mature (Crane et al., 2020b). Like avocado, the months during which mangoes mature varies with variety. Fruit on the same tree mature at different times, especially if parts of the tree flower at different times. Indicators of mango fruit maturity include:

- broadening of the shoulders and fruit tip (Figure 2).

- softening of the fruit.

- slight change in peel color from green to shades of yellow or red; peel color of some varieties (e.g, Keitt) is not a reliable indicator of maturity.

- time from flowering to maturity (typically 4 to 5 months [Morton, 1987]).

Papaya

Papaya are fast-growing fruit trees with tall, non-branching trunks. Fruit form directly from the main stem above nodes where leaves once formed. Papaya provides a farmer with a harvest in as little as 6-11 months and yields up to 36 kg of fruit each year (Morton, 1987; Crane, 2020a). Papaya can be used green as a starchy vegetable or ripe as a sweet dessert fruit. Here, we focus on determining the harvest windows for papaya eaten ripe. Yellow coloration on the exterior of the fruit is the primary indicator of ripeness. Indicators of papaya fruit maturity include:

coloration of fruit surface (Figure 3). Fruit can be harvested (with the peduncle intact) when as little as 10% of the fruit’s surface turns yellow, but the longer the fruit is left on the tree, the higher the sugar content and therefore the sweeter the fruit (Crane, 2020a). Pay close attention to fruit as they are turning yellow. If left on the tree too long, animals such as racoons, baboons, or insects will damage and consume the fruit. A general rule is that if 33% of the fruit’s surface turns yellow, harvest it for peak sweetness/flavor without risking losses. If transporting fruit a long distance over bumpy terrain, you may want to harvest closer to 10% surface yellowing to prevent fruit damage in transport.

increase in fruit weight from accumulated sugars and water. This also increases the chances of the fruit dropping from the tree before being harvested.

After harvesting, fruit should be left in ambient temperatures until it fully ripens. Fruit stored at or above 30°C and high humidity will continue to ripen rapidly. Fruit will not continue to ripen if stored in temperatures below 10°C (Morton, 1987).

Figure 3. Papaya at different stages of ripeness from unripe green (left) to completely ripe (right). Source: Tim Motis

Tomato

Figure 4. Tomatoes at varying stages of color development. Source: Stacy Swartz

Tomatoes ripen from the inside of the fruit to the outside as chlorophyll degrades and the synthesis of carotenoids increases (Carrillo-López and Yahia, 2014). Tomatoes must be harvested at or after the mature stage to fully ripen normally after harvest. When mature but green, the tomato has started to ripen and if dissected, you will see coloration on the inside. This destructive sampling makes the fruit unmarketable and individual tomatoes can ripen at different rates (Figure 4), so it is not recommended to attempt harvesting tomatoes at the mature green stage. Indicators of tomato fruit maturity include:

- initial change of color. The earliest harvest stage, called the breaker stage, is characterized by a definite change in the color of up to 10% of the fruit surface (Sargent, 1998). Depending on the variety of the tomato this could be pink, tan, black/purple, yellow, or red coloration of the fruit surface. Fruit are still firm at the breaker stage and therefore easier to transport.

- size of the fruit should reach the minimum expected for the variety.

- fruit shape should be what is expected of the variety and the ‘shoulders’ of the fruit should be fully formed.

- fruit surface should be waxy or glossy in appearance when ripe.

- brown tissue is visible where the stem meets the fruit, called stem scar (Sargent, 1998).

Starfruit

Starfruit trees typically produce multiple harvests a year, but fruit need to be fully ripened on the tree as sugar content does not increase after removal from the tree. These attributes make these trees desirable for home garden settings when they can be harvested and eaten immediately or within a few days. Transport of starfruit for sale at market has more challenges but is done around the tropics. Farmers balance tradeoffs of fruit sweetness and fruit damage in transport. Similar to tomatoes, starfruit ripens from the center to the exterior of the fruit, changing from green to yellow-orange as it ripens. Depending on variety, agricultural practices, and weather, fruit take 60 to 75 days to fully mature on the tree (Crane, 2020b). Indicators of starfruit fruit maturity include:

- only small amounts of green remain on the wings of the fruit. At this point, the fruit has reached peak ripeness for harvesting.

- fruit reach the minimum expected size for the variety which can be between 5 and 15 cm (Crane, 2020b).

- fruit exterior should be waxy.

- fruit texture changes from firm (unripe or half-ripe) to soft (ripe) (Muthu et al., 2016; Figure 5).

- fruit easily break off from the branch with a gentle tug.

Harvest carefully as there may be insects such as wasps consuming the fruit when it is ripened on the tree. Like other fruit in the Oxalidaceae family, star fruit have high levels of oxalic acid (9.6 mg/100g in mature fruit; Muthu et al., 2016) and should not be consumed by individuals with chronic renal problems.

Figure 5. Starfruit at varying stages of ripeness from unripe (left) to overripe (right). Source: Stacy Swartz

Banana

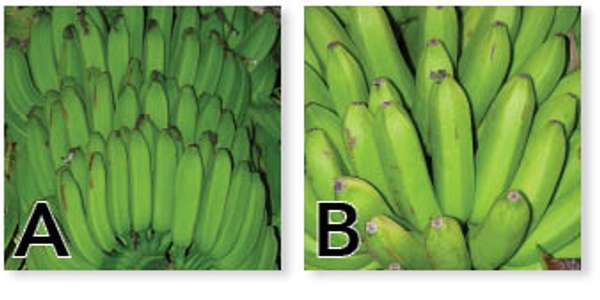

Figure 6. Unripe, green bananas at an immature (A) and mature (B) stage. The green mature bananas have reached full size and are less angular than the immature green bananas. Source: Tim Motis

Bananas are cultivated around the world and are eaten at various stages of ripeness. Green bananas are cooked and consumed for their high caloric value while ripe bananas are eaten as a sweet, fresh fruit and are high in potassium. Certain varieties are more suitable for eating green while others are the ‘dessert’ type. Here, we focus on determining the harvest windows for bananas eaten fresh, not cooked. Banana pseudostems 1 produce fruit throughout the year in the tropics and subtropics, but are more productive during wet, warm conditions than in dry, cool conditions. Depending on abiotic factors such as sunlight and temperature as well as internal plant factors such as plant age, a flower will emerge from the pseudostem after the 26th to the 32nd leaf (Crane and Balerdi, 2020). At this time, the pseudostem will have reached the expected height for the variety and instead of a flag leaf (the last leaf to emerge before a flower), a flower will emerge from the center of the pseudostem. Banana bunch ripening depends on temperature and sunlight, but bunches typically ripen between 75 and 90 days after the opening of the first hand (Morton, 1987; Martin, 1998). Indicators of banana fruit maturity include:

- individual banana fruit (sometimes called fingers) have rounded edges, becoming more swollen than angular (Morton, 1987; Crane and Balerdi, 2020). This is not true for plantains, which keep their angular appearance. Bananas will still be firm and green at this time (Figure 6), but will still ripen well after harvest.

- banana fruit have grown to reach the expected size for the variety (Crane and Balerdi, 2020). This is another indicator of maturity while the fruit are still green.

- upper banana clusters/hands in the bunch start turning light green or yellow.

- insects or other animals start eating the upper clusters, often leaving brown scratch marks.

- the end banana fruit on the first cluster/hand (the first flower to be fertilized) begins to droop or lean away from the other hands.

Because bananas are climacteric fruit, they are often harvested at early stages of ripeness while fruit is still green and firm so that fruit is not damaged in transport.

One pseudostem will only produce one bunch of banana fruit. After harvest, cut down the pseudostem and terminate the meristem (growing point) located at the center of the corm. After fruit harvest, pseudostems can be chopped and fermented to feed to livestock, as described in Asia Note #42 (http://edn.link/q3mcc9) and demonstrated in this video (http://edn.link/dfy2ay), or can be cut up and mulched at the base of the banana clump which recycles some of the potassium required in high amounts for banana production.

| Fruit name | Early indication of ripening | Signs of peak ripeness | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avocado (Persea americana) |

Season of maturity | Separation of fruit from seed | Sign of peak ripeness indicated by rattling sound when shaken. |

| Mango (Mangifera indica) | Broadening of the shoulders | Loss of green peel color and yellow to orange flesh color | A mango is ready to pick if the stem snaps easily when pulled (Morton, 1987). |

| Papaya (Carica papaya) |

At least 10% fruit surface is yellow | 33% or more of the fruit surface is yellow | Can wait until up to 80% of fruit is yellow before harvesting to achieve greatest flavor (Morton, 1987), but risk loss to drop or animals. |

| Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) |

Any amount of coloration observed on fruit surface, appropriate size and shape for variety | Full coloration (even the fruit shoulders) | Local market preferences will also influence appropriate harvest timeframe(s). |

| Starfruit (Averrhoa carambola) |

Coloration of fruit from green to yellow | Minimal green left on the tips of fruit wings | When overripe, fruit begins to turn brown starting at the tips of the wings. Harvest before brown coloration begins. |

| Banana (Musaceae family) | Rounding of fruit edges Fruit is swollen to expected size |

Upper clusters of fruit turn yellow | Uses and appropriate harvesting windows depend on variety and use of fruit. |

Final Thoughts

Knowing end user or market preferences will help guide harvest decisions. If the end user is more concerned with flavor than appearance, farmers will want to harvest later for peak flavor and/or sweetness of fruit. If the end user is more concerned with appearance, farmers will want to harvest fruit when they notice early indicators of ripeness. Early and peak windows of ripeness are described in table 2.

Some fruit retain better flavor when harvested in the morning such as papaya and starfruit, while other fruit are more flavorful when harvested in the afternoon such as tomato. For fruit like avocado and mango, flavor does not vary greatly based on time of day though there may be other factors for harvesting at a specific time.2

Harvest fruit carefully, especially when fruit like papaya and tomato are at an advanced stage of ripeness and are soft. This avoids punctures, which can lead to disease. Future EDN content will discuss other ways to minimize disease and preserve fruit quality as long as possible.

References

Carrillo-López, A. and E.M. Yahia. 2014. Changes in color-related compounds in tomato fruit exocarp and mesocarp during ripening using HPLC-APcl+ - mass Spectrometry. Journal of Food Science Technology. 51(10): 2720-2726.

Crane, J.H. 2020a. Papaya growing in the Florida home landscape. Publication #HS11. Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Crane, J.H. 2020b. Carambola growing in the Florida home landscape. Publication #HS12. Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Crane, J.H., and C. F. Balerdi. 2020. Banana growing in the Florida home landscape. Publication #HS10. Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Crane, J.H, C.F. Balerdi, and I. Maguire. 2020a. Avocado growing in the Florida home landscape. Publication #CIR1034. Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Crane, J.H., J. Wasielewski, C.F. Balerdi, and I. Maguire. 2020b. Mango growing in the Florida home landscape. Publication #HS2. Horticultural Sciences Department, University of Florida/Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Esguerra, E.B, and R. Rolle. 2018. Post-harvest management of mango for quality and safety assurance. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Rome.

Kader, A.A. 2002. Postharvest biology and technology: An overview, pp. 39-47 (chapter 4). In: A.A. Kader (ed.) Postharvest technology of horticultural crops. University of California. Agriculture and Natural Resources, Davis, California.

Lee, S.K., R.E. Young, P.M. Schiffman, and C.W. Coggins, Jr. 1983. Maturity studies of avocado fruit based on picking dates and dry weight. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science 108:390-394.

Martin, F.W. 1998. Banana, Coconut & Breadfruit. ECHO Technical Note no. 34.

Morton, J.F. 1987. Fruits of Warm Climates. Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Muthu, N., S.Y. Lee, K.K. Phua, and S.J. Bhore. 2016. Nutritional, medicinal and toxicological attributes of star-fruits (Averrhoa carambola L.): A Review. Bioinformation 12(12):420-424.

Sargent, S.A. 1998. Tomato Production Guide for Florida: Harvest and Handling. SP-214. Cooperative Extension Service, University of Florida/ Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences.

Thakur, K.S. and S. Sharma. 2019. Fruit maturity and ripening. In: Fruit Science. New India Publishing Agency.