This article summarizes ECHO research conducted by Boonsong Thansrithong, Abram J. Bicksler, and Patrick J. Trail.

Introduction

Relevance

Figure 7. Coffee berry halved showing silverskin and parchment covering (left) and two coffee beans without coverings (right). Source: Jonathan Ribich and Stacy Swartz

The global coffee (Coffea spp.) industry produced around 10.8 million metric tonnes of green coffee in 2022 (FAOSTAT, 2024) and, along with it, an enormous amount of waste. For every tonne of coffee harvested by the Indigenous Tribal Development Project in northern Thailand, they found that as little as 25% resulted in marketable green coffee. The remaining percentage accounts for ‘waste’ by-products that include coffee cherry pulp, mucilage, parchment, and discarded beans.

The final step in processing green coffee (Coffea arabica) is removing the outer endocarp layer of the coffee bean, commonly referred to as ‘parchment’ (Figure 7). Coffee processing centers remove the parchment before shipping or roasting coffee beans, accumulating an unwanted by-product. Methods of parchment disposal include burning or simply leaving it in piles to decompose, both of which can be environmentally hazardous at a large scale.

Simultaneously, the dairy industry seeks to source large quantities of low-cost fiber to include in feed regimens. They face the continual challenge of low profit margins and fluctuating feed component prices. Coffee parchment has high fiber content (Negesse et al., 2009), as much as 83.6% Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF)3 (Vilela et al., 2001). Its supply often outweighs its demand, making it an affordable, if not free resource in many parts of the coffee-producing world. This has led researchers to consider using coffee parchment as a livestock feed component (Didanna, 2014; Mazzafera, 2002).

Research purpose

ECHO Asia staff conducted this research with a main objective of replacing a portion of the purchased fiber component in dairy cattle feed with free coffee parchment and evaluating its effects on milk production. Our research is relevant to regions where coffee parchment does not have high demand and can be obtained at no cost. Farmers interested in this feed option must consider the time, labor, and transportation costs associated with using coffee parchment resources.

Methods

We conducted this experiment during 2016 and 2017 in northern Thailand, at the MMM Dairy Farm in San Kampaeng, Chiang Mai District.

Feeds

Figure 8. Farm made feed with coffee parchment before mixing. Source: ECHO

Figure 9. Dairy cows at MMM Dairy Farm. Source: ECHO

The experiment comprised three individual trials. In each trial, we used coffee parchment to provide a set portion of the fiber content of the farm-made feed (Figure 8). The coffee parchment used in these experiments came from Coffea arabica processed using the wet method.4 In the first run of the experiment, we supplemented 200 g of coffee parchment into the daily feed of 19 randomly selected tropical Holstein milking cows. In runs 2 and 3, we supplemented 1 kg of coffee parchment into the daily feed of 16 randomly selected milking cows of the same herd. We fed each cow 25 kg of the supplemented farm-made feed (Table 1; Figure 9) each day for one-month, in addition to 5 kg of commercial feed concentrate each day.

| Ingredient | Amount (kg) | Cost (THB/kg) | Cost (USD/kg) | Total Cost with Parchment (THB) | Total Cost with Parchment (USD) | Total Cost without Parchment (THB) | Total Cost without Parchment (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corn Silage | 650 | 1.8 | 0.05 | 1,170 | 32.19 | 1,170 | 32.19 |

| Cassava Meal | 400 | 1.3 | 0.04 | 520 | 14.31 | 520 | 14.31 |

| Dry Corn Husks | 150 | 2 | 0.06 | 300 | 8.25 | 500 | 13.74 |

| Canned Fruit Syrup | 5 | 2 | 0.06 | 10 | 0.28 | 10 | 0.28 |

| Coffee Parchment | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 1,305 | 2,000 | 55.03 | 2,200 | 60.44 |

Measurements

We sent milk samples of individual cows for quality testing before and after a one-month period of feeding them the coffee parchment-supplemented farm-made feeds. The Maejo Agricultural University in Chiang Mai, Thailand performed the milk quality tests. They measured dependent variables of fat, crude protein, lactose, total solids, and somatic cell counts. The Thailand Livestock Development Department assisted in procuring the tests.

Fat, crude protein, lactose, and total solids levels are indicators of milk quality and can be impacted by a cow’s diet. Decreases in these parameters at the end of the feed trial would indicate a negative effect that may have come from the diet change.

Somatic cell count5 is used as an indicator of both milk quality and livestock health. Any increase in somatic cell count, at the end of the feed trial, would indicate a negative effect that may have come from the diet change.

Results

Milk quality

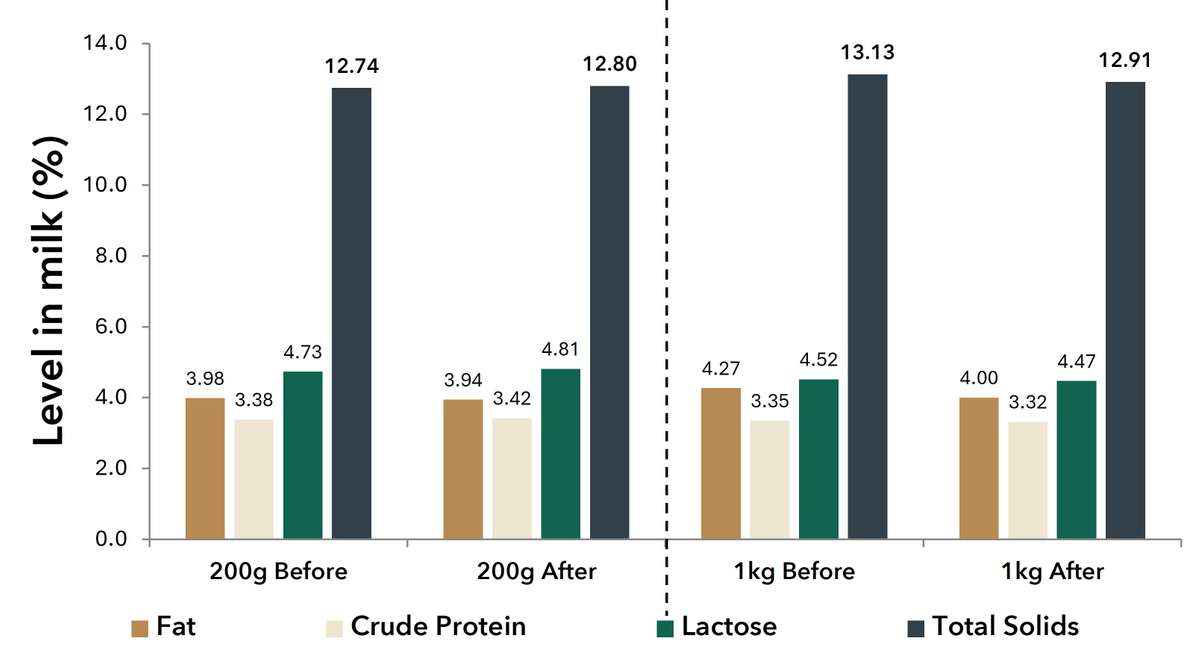

There were no statistically significant differences in any milk quality measurements before and after cows received the farm-made feed supplemented with either 200 g or 1 kg of coffee parchment (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Percentage of fat, crude protein, lactose, and total solids before and after feeding trials when 200 g and 1 kg of coffee parchment were respectively incorporated into the total daily ration of each cow.

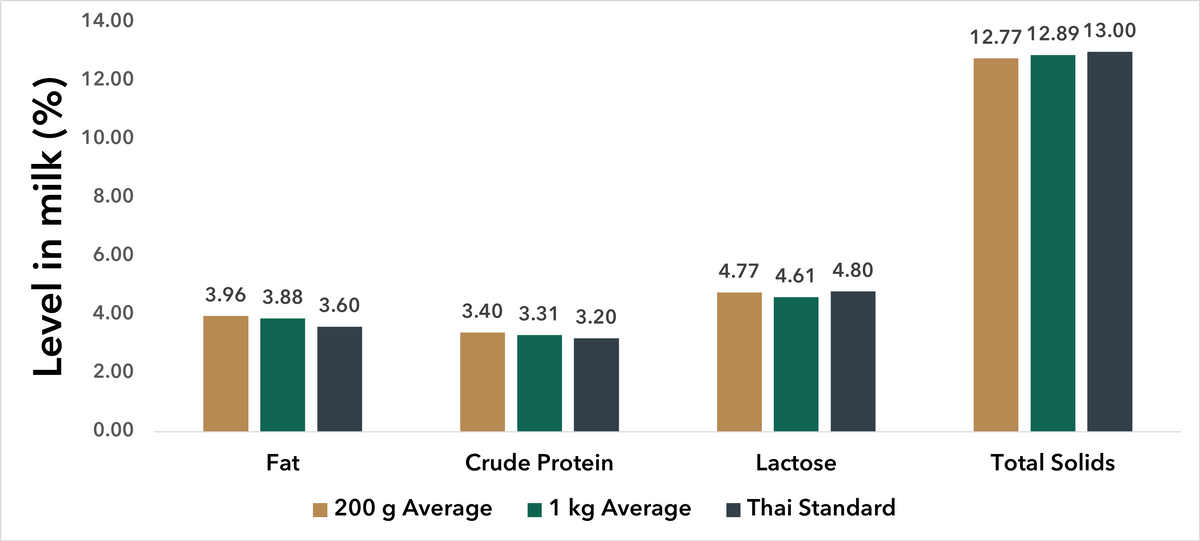

The milk quality measurements from the experiment were comparable to the Thai standards for milk quality (Figure 11; Milk Quality Check, 2010; Committee of Dairy Milk and Dairy Milk Products, 2015).

Figure 11. Averaged milk quality measurements compared to Thai standards (Milk Quality Check, 2010; Committee of Dairy Milk and Dairy Milk Products, 2015). Values were averaged across results before and after feed treatments.

Livestock health

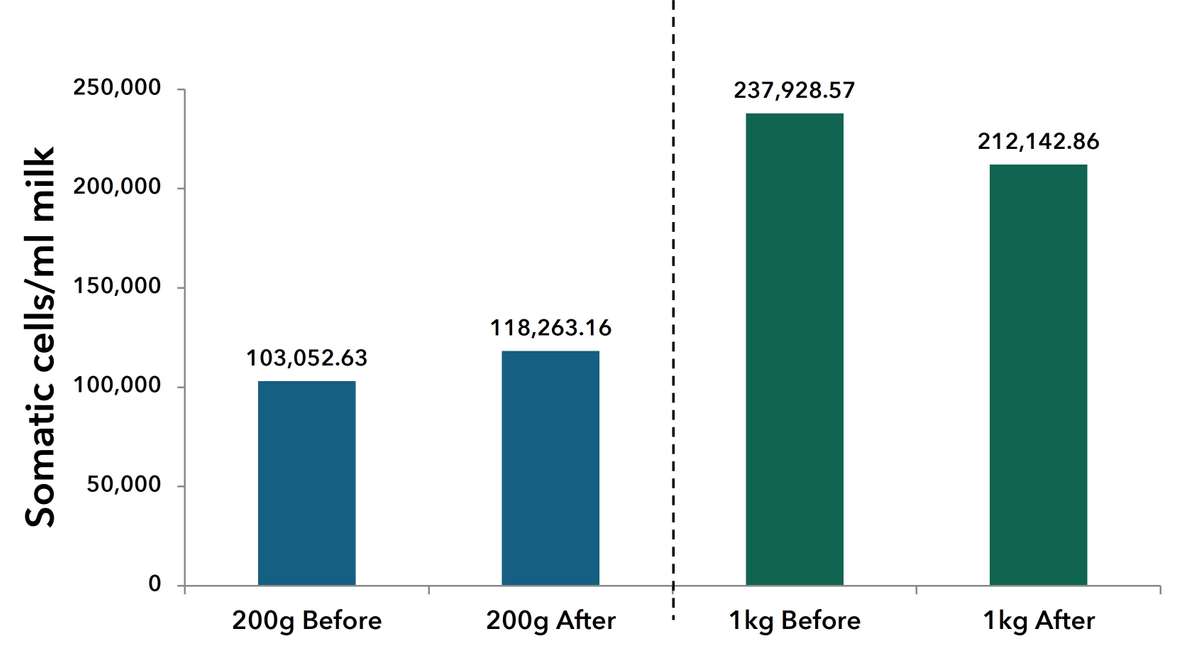

In addition, we observed no statistically significant differences in somatic cell counts before and after cows received the farm-made feed supplemented with either 200 g or 1 kg of coffee parchment (Figure 12). The somatic cell counts in all of the trials were well below the Thai Agricultural Standard threshold of 500,000 cells/ml for raw milk (National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards, 2010).

Figure 12. Somatic cell count before and after feeding trials when 200 g and 1 kg of coffee parchment were respectively incorporated into the total daily ration of each cow.

Economic impact

The addition of fiber from coffee parchment allowed us to reduce the amount of fiber from purchased feed components in the farm made feed (Table 1). This resulted in a 10% savings for every 1,305 kg of farm-made feed that we produced. Over the period of a month, we saved approximately USD $50, or USD $2.50 per cow, by using feed supplemented with coffee parchment.

Discusion and conclusions

Adding a limited quantity of coffee parchment to dairy feed rations has the potential to reduce dairy farmers’ costs and create a market for a waste coffee by-product. Our results indicate that up to 1 kg of coffee parchment may be used per dairy cow as a daily fiber supplement without negatively impacting milk quality or livestock health. The cows refused to eat coffee parchment by itself, preferring to consume it mixed with the other farm-made feed components.

We suggest that future researchers run further experiments using feed supplemented with 1 kg of coffee parchment for longer durations to assess the possibility of long-term effects.

References

[Committee of Dairy Milk and Dairy Milk Products. Thai Raw Milk Standards for Buyers]. 2015. In: Dairy Farming Promotion Organization of Thailand website. Announcedpurchaserawmilk2015.pdf (dpo.go.th)

Didanna, H.L. 2014. A critical review on feed value of coffee waste for livestock feeding. World Journal of Biology and Biological Sciences. 2(5):72-76.

FAOSTAT. Crops and Livestock Products. Accessed May 14, 2024. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

Mazzafera, P. 2002. Degradation of caffeine by microorganisms and potential use of decaffeinated coffee husk and pulp in animal feeding. Scientia Agricola. 59(4):815-821.

[“Milk Quality Check”] [Chapter 2]. 2010. http://cmuir.cmu.ac.th/bitstream/6653943832/19793/5/anim1049rs_ch2.pdf

National Bureau of Agricultural Commodity and Food Standards. 2010. Thai Agricultural Standard: Raw Cow Milk. 2010. In: Royal Gazette Vol. 127:131 D. https://faolex.fao.org/docs/pdf/tha166328.pdf.

Negesse, T., H.P.S. Makkar, and K. Becker. 2009. Nutritive value of some non-conventional feed resources of Ethiopia determined by chemical analyses and an in vitro gas method. Animal Feed Science and Technology. 154(3-4):204-217.

Vilela, F. G., J.R.O. Perez, J.C. Teixeira, and S.T. Reis. 2001. Use of sticky coffee hull for feeding of steers in feedlots. Ciencia e Agrotecnologia, 25 (1):198-205.

Cite this article as:

Ribich, J., P. Trail, B. Thansrithong, and A. Bicksler. 2024. Coffee Parchment as a Feed Supplement for Dairy Cattle. ECHO Development Notes no. 164.