ECHO Asia Note Articles

ECHO Asia Notes is a quarterly technical e-bulletin containing articles of interest to agriculture and community development workers in Asia.

This list contains articles from ECHO Asia Notes, many of which have been translated into regional languages.

101 Issues in this Publication (Showing issues 44 - 40) Previous | Next

Cyantesmo Paper for Detecting Cyanide

- Also available in:

- English (en)

- မြန်မာ (my)

- Bahasa Indonesia (id)

- ភាសាខ្មែរ (km)

- Tiếng Việt (vi)

- ไทย (th)

- 汉语 (zh)

Some tropical crops contain cyanogenic glycosides, toxic substances that release hydrocyanic acid (HCN; also referred to as cyanide or prussic acid) when cells are crushed. Consuming these plants without cooking them can cause cyanide poisoning, with varying effects depending on cyanide levels and how long a person or animal has been eating that plant. Cassava roots and leaves contain cyanogenic glycosides, so people whose diets are heavily dependent on cassava are especially at risk. Traditional methods to process and detoxify cassava roots include fermentation, prolonged soaking and boiling. Chaya leaves also contain cyanogenic glycosides; it is best to cook chaya leaves before eating them, to boil off the HCN rather than ingesting it. ECHO has previously written about cyanide in food plants.

To determine if a plant is safe to consume, either by humans or livestock, a simple cyanide screening test is very helpful. At the 2014 ECHO International Agriculture Conference in Florida, Dr. Ray Smith provided ECHO with sample strips of Cyantesmo paper for screening plant material for HCN. A 2.5 cm (1 in.) strip of this paper is all that is needed to detect the presence of cyanide in a sample of plant material. Cyantesmo paper is available in a 5-m long roll for 49.50 US dollars from CTI Scientific (item 90604). One roll supplies enough 2.5-cm long paper strips for 200 tests. The paper does not have to be kept in a freezer, although Smith recommends that it be refrigerated.

Do all parts of a chaya plant contain hydrocyanic acid?

- Also available in:

- မြန်မာ (my)

- Tiếng Việt (vi)

- ไทย (th)

- English (en)

- 汉语 (zh)

- ភាសាខ្មែរ (km)

- Bahasa Indonesia (id)

Leaves of tropical crops like chaya (Cnidoscolus aconitifolius) and cassava (Manihot esculenta) contain cyanogenic glycosides, toxic substances that release hydrocyanic acid (HCN; also referred to as cyanide or prussic acid) when cells are crushed. Consuming these plants without cooking them can cause cyanide poisoning, with effects that vary depending on cyanide levels and how long a person or animal has been eating that plant. An information sheet from the New Zealand Food Safety Authority describes cyanogenic glycosides in plants and their effect on human health. To determine if a plant is safe to consume, a simple cyanide screening test using Cyantesmo paper is very helpful.

Tomato Grafting in Southeast Asia: A Useful Technique for Rainy Season Production

- Also available in:

- ភាសាខ្មែរ (km)

- हिन्दी भाषा (hi)

- ไทย (th)

- 汉语 (zh)

- Tiếng Việt (vi)

- Bahasa Indonesia (id)

- မြန်မာ (my)

- English (en)

Tomatoes are difficult to grow during Southeast Asia’s hot and humid monsoonal rainy season. A combination of waterlogged soils, increased disease pressure, and high temperatures often kill young tomato transplants or significantly reduce yields. As an introduced crop, originally from South America, tomatoes are not well adapted to all Southeast Asian climates and soils, and can struggle to produce in the wetter conditions of the region.

Many of the tomatoes found in the marketplace and used by restaurants and hotels during the rainy season are imported or greenhouse-grown, commanding a premium price. This provides a unique opportunity for any local farmers capable of successfully producing to markets during this ‘off season’ window. While growing tomatoes on raised beds or in rain shelters is becoming common practice, grafting is an additional tool that can be used by farmers to produce tomatoes with an improved profit margin.

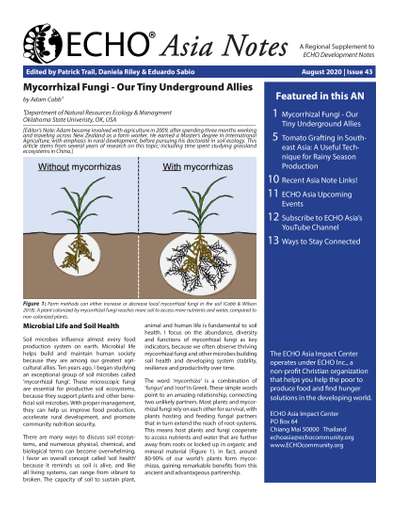

Mycorrhizal Fungi - Our Tiny Underground Allies

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 43

Soil microbes influence almost every food production system on earth. Microbial life helps build and maintain human society because they are among our greatest agricultural allies. Ten years ago, I began studying an exceptional group of soil microbes called ‘mycorrhizal fungi’. These microscopic fungi are essential for productive soil ecosystems, because they support plants and other beneficial soil microbes. With proper management, they can help us improve food production, accelerate rural development, and promote community nutrition security.

There are many ways to discuss soil ecosystems, and numerous physical, chemical, and biological terms can become overwhelming. I favor an overall concept called ‘soil health’ because it reminds us soil is alive, and like all living systems, can range from vibrant to broken. The capacity of soil to sustain plant, animal and human life is fundamental to soil health. I focus on the abundance, diversity and functions of mycorrhizal fungi as key indicators, because we often observe thriving mycorrhizal fungi and other microbes building soil health and developing system stability, resilience and productivity over time.

Making On-Farm Pig Feed: Farm-Generated Formulas vs. Commercial Feeds

- Also available in:

- Bahasa Indonesia (id)

- English (en)

- Tiếng Việt (vi)

- မြန်မာ (my)

- 汉语 (zh)

- हिन्दी भाषा (hi)

- ไทย (th)

- ភាសាខ្មែរ (km)

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 42

The integration of livestock on the smallholder farm is often a key component to the long-term sustainability of the farm, specifically by means of critical nutrient cycling. Livestock play a unique and critical role on the farm, transforming plant and waste materials into important sources of energy, either for consumption on the farm, or for sale beyond it. As omnivores, pigs are one of the most efficient converters of on-farm ‘waste’, transforming materials unsuited for human consumption, into meat, manure, and income.

On the ECHO Asia Farm we seek to create our own ‘Farm-Generated Feeds’ for the purpose of leveraging the materials we have available to us, while bringing down our costs of livestock production. In addition to the meat and income produced through our cows, pigs, chickens, and fish, we also value them for their manure, which we compost and use in crop production among other things.

ECHOs from the Network: Coffee Drying ‘Bunk-Beds’ for Vegetable Production - 2020/05/29

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 42

During the coffee harvest season, we find ourselves maxing out every available drying table that we have while processing our coffee. At the Behind the Leaf Coffee Processing Center, we have 122 drying tables, and for 4 months of the year we use every table we have to lay out and dry the fresh cherries. Unfortunately, there are 8 months of the year that we are not using those drying tables, and they take up significant space. Over the years we have experimented with multi-use table alternatives but have largely been unable to take advantage of the land dedicated to drying coffee.

ECHOs from the Network: Integrated Pest Management on the Island of Bali - 2020/05/29

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 42

On the island of Bali we have had recent challenges with the Sugarcane White Grub (Lepidiota stigma) consuming many different crops and frustrating local farmers. In Bali (and Sumatra) we call this pest ‘gayes’, in Javanese it is known as ‘urèt’. In our region, it is a major pest in dryland cropping areas, with the grubs consuming the roots of sugar cane, maize, sorghum, cassava, banana, and other crops. Gayes has always been around, but only in recent years has it become a major pest problem, quickly getting out of control. It has been so bad that some farmers have given up on their fields completely and have abandoned them to grow in other areas. One reason the population has exploded is that back in the olden days people liked to pick and eat the grubs for food, but now the younger generation is not interested.

Black Soldier Fly System of the Frangipani Langkawi Organic Farm

- Also available in:

- Bahasa Indonesia (id)

- ไทย (th)

- English (en)

- မြန်မာ (my)

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 41.

[Editor’s Note: Anthony Wong the Managing Director of the Frangipani Langkawi Resort in Langkawi, Malaysia and is a longtime steward of green initiatives in Malaysia and the region. Using constructed wetland systems, grey water at his hotels are cleaned and recycled, while large amounts of food waste are up-scaled using an innovative Black Soldier Fly system. Mr. Wong was a recent speaker at the ECHO Asia Agriculture & Development Conference in 2019 and has many years of practical hands-on experience. For further reading and details we would also recommend the Black Soldier Fly Biowaste Processing – A Step-by-Step Guide.]

Integrating Black Soldier Flies on the Farm

The BSF or Black Soldier Fly (Hermetia illucens) brings great potential to any farming system through its ability to consume on-farm waste and produce a highly nutritious feed source. The larvae of the BSF can be grown using nearly any organic waste product, and can be used to up-cycle waste materials into a valuable protein source. BSF have the ability to break down waste resources that cannot be directly fed to humans or livestock, or even worms in a vermicomposting system, thereby making these systems valuable in tightening the nutrient cycle on any farm. In addition to the feed that the larvae becomes, the secondary advantage is their ability to rapidly break down food waste to produce a valuable by-product that can be used as an organic soil amendment.

A Snapshot of the ECHO Asia Small Farm Resource Center & Seed Bank - 2020/03/13

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 41.

With a new decade upon us, the ECHO Asia team is pleased to highlight the next chapter in its engagement with the Asia regional network. Many of you are well aware of the goings on of ECHO Asia, but for some it may come as news that we have launched a new farm site. We are therefore eager to publicize to our network the opening of the ECHO Asia Small Farm Resource Center & Seed Bank or ‘ECHO Asia Farm’ (Fig. 1). With this new opportunity ECHO Asia is pleased to share this occasion for growth and expansion.

Two years ago ECHO Asia was blessed beyond measure through the gracious donation of a beautiful tract of land, located just 25 minutes outside of the city of Chiang Mai, Thailand. This 3 hectare (7 acre) parcel of land is located on the site of a former aquaculture enterprise, and has been entrusted to us for the use and benefit of our network partners. We are collectively grateful to God for this blessing, and have chosen to dedicate this site to the service of our network and the farming communities that we ultimately serve.

State of Land in the Mekong Region - Brief

- Also available in:

- English (en)

- ไทย (th)

- မြန်မာ (my)

This article is from ECHO Asia Note # 40.

The Mekong region lies at the intersection of Southeast, East and South Asia, between two Asian giants: China and India. It comprises five countries that host the bulk of the Mekong river watershed: Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam. The Mekong region is exceptional for its social and ecological richness. Home to 237 million people, the region includes 329 ethnic groups speaking 410 distinct languages, making the region one of the most ethnically-diverse in the world. The Mekong is also a global biodiversity hotspot, with a high degree of ecological and agricultural diversity.

The Mekong region has undergone rapid socio-economic growth over the past two decades alongside pronounced transformations in a number of key sectors. These changes have significantly altered relations between the rural majority and increasingly-affluent urban centres. Land—as both a foundation for national development and the livelihoods of millions of rural and agricultural communities—continues to play a central role in the Mekong region. In all five countries, smallholder farmers play a crucial role in the development of the agricultural sector and, through it, food security and economic growth. However, rural communities are being increasingly swept up into regional and global processes within which they are not always well-positioned to compete. Worse, they are often undermined by national policies that fail to ensure their rights or enable them to reap potential benefits.

Understanding the changing role and contribution of land to development is critical to inform policy, planning and practices toward a more sustainable future. The State of Land in the Mekong Region aims to contribute to a much-needed conversation between all stakeholders by bringing together data and information to identify and describe the key issues and processes revolving around land, serving as a basis for constructive dialogue and collaborative decision-making.